Viewpoint: Ukraine, the EU and Tymoshenko

- Published

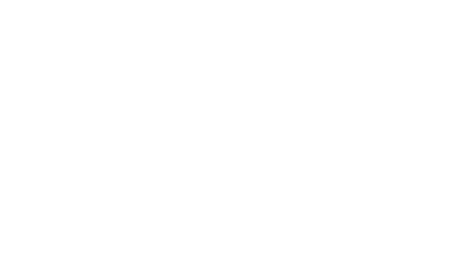

The European Union says the jailing of former Ukraine leader Yulia Tymoshenko will have profound implications for its future relations with Ukraine. Andrew Wilson, an expert on Ukrainian affairs, explains why.

A verdict has finally been delivered in the trial of Yulia Tymoshenko, the former prime minister of Ukraine. For a month, the authorities have been playing a game of grandmother's footsteps, external with the West, as they tried to avoid delivering a verdict during awkward events like the visit of international dignitaries to the annual YES Yalta summit in Crimea, or the EU's eastern partnership summit in Warsaw.

Still, the Ukrainians got a tough message by EU standards. For some time now, Ukraine has been trying to finalise a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with Brussels - which is more important than it sounds.

In the absence of an EU membership perspective, a DCFTA would help transform Ukrainian society by introducing EU standards in the way that states like Poland or Estonia were transformed in the 1990s.

Before the verdict, these agreements were still on track to be signed in December, but the EU had made it clear that depended on Tymoshenko staying out of prison and the Ukrainian authorities were hinting at some messy, face-saving compromise.

So many were shocked by the severity of the verdict. Tymoshenko was sentenced to seven years, and must pay a fine of $190m (£122m). She is banned from running for office for three years, which would rule her out of the next elections, for parliament, in 2012.

Tymoshenko's trial was held in a tiny court.

The trial itself was already an embarrassment. To try and discourage too many attendees, it was held in a tiny court, which became a packed circus. A young and inexperienced judge failed to defend principles of sub judice in the face of a stream of prejudicial comments from state officials.

The authorities switched from one accusation to another before the trial. Worst of all was the failure to provide a smoking gun once they decided the main charge would be Tymoshenko's role in the gas price negotiations with Russia in 2009.

Tymoshenko settled for a high price, which cost Ukraine dear; but this was just after the infamous cut-off that left much of Europe freezing in January 2009, and most observers assumed it was the price for potential Russian support in the 2010 presidential election and for levering the notorious intermediary company Rosukrenergo out of the market.

Tymoshenko also paid a high price; she lost the election narrowly to now President Viktor Yanukovych by 45.5% to 48.9%.

The trial uncovered nothing more that looked like real criminal culpability.

Gas key

Gas has, in any case, always been a political football between Russia and Ukraine.

Mr Yanukovych paid a high price again in April 2010, when he agreed a fleeting discount with Russia on the gas price in return for extending the lease of the Russian Black Sea fleet in Crimea for 25 years.

Russia and Ukraine are again at loggerheads over the price of gas today.

The Ukrainian newspaper Dzerkalo tyzhnia alleges Mr Yanukovych paid an even higher price in secret while he was prime minister in the run-up to the 2004 election that sparked the Orange Revolution.

The verdict on Ukraine is much clearer. Mr Yanukovych has been recentralising power by questionable means ever since the 2010 election.

Too many people bought the argument that order and stability were important after the chaotic and corrupt democracy ushered in by the Orange Revolution.

Appeal likely

The Tymoshenko trial in 2011 has at least been a wake-up call after too many blind eyes were turned in 2010.

But the verdict is far from the last word. Appeal is inevitable. It is possible that parliament will agree to decriminalise the sections of the criminal code under which Tymoshenko was charged.

But unless Ukraine signals that this will happen pretty quickly, it will be too late.

Having drawn such a clear red line, the EU (and the US) cannot back down now. The DCFTA must be put on hold.

There are still some who argue not to throw the baby out with the bath water. Given time, the EU agreements will undercut the power of the corrupt ruling elite by slowly transforming and opening up the Ukrainian economy and society.

But this is a false dilemma. Ukraine will never transform itself until its politics is right. And Europe cannot hope to have much influence in the wider world if it cannot even wield it in a near-neighbour like Ukraine.

Andrew Wilson is Reader in Ukrainian Studies at University College London and a Senior Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. His books on Ukraine include, among others, The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation.

- Published11 October 2011

- Published11 October 2011

- Published23 May 2014

- Published30 September 2011

- Published17 August 2011