Greece keeps eurozone guessing

- Published

- comments

The eurozone crisis has shot to the top of the G20 agenda in Cannes

Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou rolled the dice, but he may prove to be the big loser.

He decided to gamble on a referendum. He calculated that a majority of Greek people would not risk voting against the bailout package agreed last week. But events have overtaken him and by the weekend he could be an ex-prime minister.

Events have moved fast. His decision to call a referendum - which had democratic merit - hammered markets around the globe. It sent the EU spinning into crisis. The agreement reached so painfully the week before was in danger of unravelling. No bank, for instance, could contemplate taking losses on their holdings of Greek debt when the future was so uncertain.

Other EU leaders were infuriated and rounded on Mr Papandreou. At the meeting in Cannes yesterday evening the French and German leaders played hardball. They made it clear they were no longer prepared to be held hostage by the Greeks.

Mr Papandreou encountered two leaders who had changed. No longer was the message that they would do all it took to keep Greece in the eurozone. Their exasperation was summed up in the message by President Sarkozy: "abide by the eurozone rules or leave".

There would be no reopening of negotiations. If there was to be a referendum it had to be held at the earliest date. They also insisted that whatever the question asked this was a referendum on whether Greece wanted to remain in the eurozone.

Also they told the Greek prime minister that the country would not receive a cent more in aid until after a Yes vote in the referendum. Greece has cash reserves only until mid-December.

Political turmoil

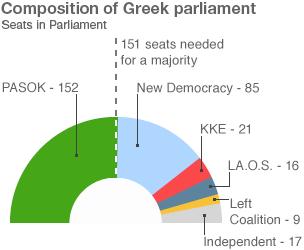

But back at home George Papandreou's support is crumbling. Voices from within his own Pasok party have called on him to resign.

Four of his ministers have said they oppose the referendum. The most damaging intervention came from the Greek Finance Minister, Evangelos Venizelos. Arriving in Cannes he issued the following statement: "Greece's position within the euro area is a historic conquest of the country that cannot be put in doubt. This acquis by the Greek people cannot depend on a referendum."

Two nights ago, whilst the Greek cabinet was debating the referendum, he had been holed up in a clinic with stomach problems. It was widely thought then that he disapproved of a referendum which he said he had not been told about.

On Friday Mr Papandreou faces a vote of confidence. There is now a strong chance he will lose it. The Papandreou era would then be over. Almost certainly Greece would move to early elections. There would be no referendum.

An early election would bring its own uncertainty, but the mood in Greece is for a strong government of national unity. Only such a government might be able to persuade the EU and IMF that Greece needs a new deal that delivers growth as well as cuts.

The future is clouded with uncertainty. It probably remains true that a majority of Greeks would vote to stay in the euro. Both the EU leaders and local politicians will paint a No vote as ushering in a period of bankruptcy and chaos. However, a significant number of people would use a referendum to register their anger with austerity. That is why a referendum would be unpredictable.

For a long period George Papandreou called on European solidarity to support his country in its hour of need. In the face of huge hostility he has pushed through cuts in wages and jobs and opened the way for vital reforms.

But even if Greece remains in the euro - which I judge as the most likely outcome - he will get no thanks. His own ranks are turning against him and his government is on the verge of collapse.