Italy crisis: What next for Silvio Berlusconi?

- Published

- comments

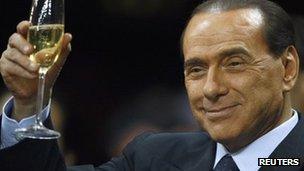

Mr Berlusconi is likely to remain an influential figure, at least in the short term

He may have resigned as Italy's prime minister, but Silvio Berlusconi will certainly not slip quietly into the shadows.

Hours after leaving the presidential palace to the jeers and boos of protesters, the billionaire businessman, external - an ex-premier but still an MP - vowed to remain centre-stage.

"To those who cheered for what they called my exit from the political scene, I want to say very clearly that I will double my commitment in parliament to renew Italy's institutions. I don't expect any gratitude, but I won't give up," he said in a video statement released on Sunday.

Although deprived of the political power of government, Mr Berlusconi, 75, remains an influential figure in Italian life, with a business empire spanning media, advertising, insurance, food and construction.

While the eurozone debt crisis gnawed away his parliamentary majority, the subsequent loss of office will likely see Mr Berlusconi focus on trying to revive his political party - and on holding the new government to account.

And a string of ongoing court cases - in which he is variously accused of using an underage prostitute, bribery and fraud and embezzlement - mean he will never be far from the headlines.

Mr Berlusconi, who could face jail if convicted, denies wrongdoing in all of the cases.

'Illegitimate'

"Berlusconi is simply not going to fade away," says Gianfranco Pasquino, a professor of political science at the Bologna centre of the Johns Hopkins University.

"He has already told us that he is going to fight to prevent the country sliding into what it is that he sees it sliding into, and he is going to be closely monitoring what the next government does in response to the crisis.

"Of course, he remains an MP and he will be trying to stop the government passing new electoral laws - it is very important to his party to maintain the status quo there, because it is very beneficial.

"And we will likely hear him argue that the technocrats appointed do not have legitimacy and he may seek to obtain from parliament an indication that they will not run for election, or use their time in office to prepare such a run."

'Underage sex'

One practical difficulty stemming from Mr Berlusconi's resignation is that he can no longer cite official government business as a reason for missing hearings in the three trials he faces.

Could Mr Berlusconi become president of the AC Milan football club, which he owns?

Prosecutors allege Mr Berlusconi paid Moroccan dancer Karima El Mahroug (aka Ruby), 17 at the time, for sex, and later made a call to have her released from a police cell over an unrelated theft charge.

The underage sex charge carries a maximum sentence of three years, while the abuse-of-power accusation is punishable by up to 12 years in prison.

In another case, Mr Berlusconi and other executives at his Mediaset broadcaster are accused of inflating the price paid for acquiring television rights via offshore companies controlled by Mr Berlusconi, in a bid to create illegal slush funds.

That trial resumed in February after Italy's constitutional court lifted Mr Berlusconi's immunity from prosecution.

In a related case, the former PM is accused of fraud and embezzlement over the acquisition of television rights for inflated prices - a preliminary hearing was held in March.

And in a third case, Mr Berlusconi is accused of paying British lawyer David Mills - the estranged husband of British Labour MP Tessa Jowell - a $600,000 (£377,000) bribe in 1997 to give false testimony in court and withhold incriminating details of business dealings.

Professor Pasquino views the court cases as a distraction which will not ultimately end in the ignominious sight of Italy's former prime minister spending time behind bars.

"Italians are not vengeful," he says. "Berlusconi is a man of 75, there is no way he will go to prison.

"These cases will proceed, probably very slowly, he may be proved guilty in certain aspects, but we will likely see the statute of limitations will kick into effect."

'Steep decline'

Dr David Hine, a tutorial fellow at Oxford University's Department of Politics and International Relations, also suggests Mr Berlusconi is "highly unlikely" to end up in prison.

But he says Mr Berlusconi is likely to find it increasingly difficult to be an influential figure in Italian politics.

"He will certainly continue to hold some immediate bureaucratic power with the party, but his credibility with the electorate is shot through.

"His poll ratings are in steep decline, and while he is still a rich man - although Mediaset's value has also come down - there is only so much you can do with that sort of money."

Meanwhile, there is plenty of speculation over other avenues that Mr Berlusconi might pursue.

His Fininvest holding company has AC Milan under its vast umbrella, and in an interview just before his departure he suggested he might become the president of the football club once again - three years after being forced to give up the role due to a conflict of interests in the wake of his 2008 election win.