The euro: Still in casualty

- Published

- comments

Ideas anyone? Italy is braced for painful cuts to tackle its massive debts

It is a measure of the depth of the eurozone crisis that it is now identified as one of the defining stories of 2011, taking its place next to the Arab Spring.

It is a crisis that has prompted frequent phone calls from the American president to Europe's leaders, urging action. His treasury secretary was despatched with growing frequency to European shores to add some muscle.

The turmoil in the eurozone crisis prompted an extraordinary intervention from the Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King. He declared it "the most serious financial crisis we have seen since the 1930s, if not ever".

As Europe edges towards the close of a year, the patient remains in casualty. It has defied all solutions.

The last summit which senior European officials billed as the meeting "to save the euro" was a non-event. The row over treaty change a distraction. The inter-governmental agreement , externallargely codified much of what had been previously agreed. It may well be helpful to enforce tighter discipline, but its impact lies in the future.

The central dilemma lies unaddressed: debt and lack of growth. Countries are squeezing down their deficits, but their debt mountains have only grown. In many European countries there is not only negligible growth but countries are sliding back into recession. The task of regaining financial health will only become harder.

Cuts stifle demand

And then there is the medicine with "Made in Germany" stamped on it. Austerity and rigour.

Country after country has been pushed into slashing spending and cutting back the public sector. However necessary, these measures will only reduce demand further.

Some countries are introducing structural reforms - like making it easier to hire and fire workers - but such growth-boosting measures will take time.

For the moment countries like Greece, Portugal, Italy and Spain appear to be in a cycle of decline, locked into years of austerity. In a common currency they do not have the flexibility to embrace different policies.

The political implications of all this can only be guessed at. Even in the best-case scenario - with investors taking 50% losses - Greece's debt-to-GDP ratio will remain at 120% by 2020.

Almost certainly there will be resistance. The Italian Prime Minister, Mario Monti, knows what is coming when he says too much austerity may split Europe. He warned against "a short-term hunger for rigour".

Young people who are bearing the brunt of unemployment may not be prepared to accept years of austerity.

All Germans now?

Germany, reluctantly, has taken over the leadership of Europe. It is not a role it sought, but its economy has given it greater influence than at any time in the past 60 years.

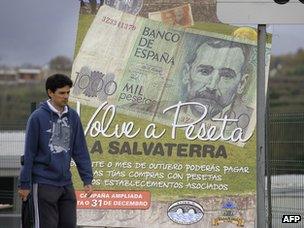

Old pesetas are back in circulation in Salvaterra, northwest Spain

It is a feature of the year past how quickly old stereotypes have re-emerged, with cartoons and pictures in many different countries depicting Angela Merkel as a Prussian, as Bismarck or even Hitler.

Chancellor Merkel has called for "more Europe". While leaders accept this when sitting around a big table in Brussels they find it far harder to sell back home.

There is strong debate in some countries over seeing some sovereignty over tax and spending plans transferred to European officials. "Sovereignty" or "who governs France" may well become an issue in the forthcoming French elections.

The crisis has removed governments and in their place unelected leaders have emerged in Italy and Greece. Increasingly the crisis over the single currency will focus attention on the state of European democracy.

Political challenge

In a year-end piece of sobering analysis the ratings agency Fitch concluded , externalthat a "comprehensive solution to the eurozone crisis is technically and politically beyond reach".

In truth many senior European officials are weary, drained from twelve months of firefighting and often pointless summits that provide drama without solutions. Sometimes - as happened during the summer - the officials and heads of government did not even understand the conclusions they signed.

At this time all eyes turn to the European Central Bank. It is cast in the role of saviour. It is now injecting vast sums into the banking system. Half a trillion euros. Leaders - bereft of any other ideas - would like to see those banks use their cheap loans to invest in sovereign debt and so lock in some profit for themselves, and at the same time drive down the borrowing costs for troubled countries like Italy and Spain.

If the crisis deepens - and large amounts of government debt have to be financed in early 2012 - the pressure will grow on the ECB to "print money", to find a way of supporting European governments and not just banks. The ECB will be at the centre of the drama in 2012.

Some Europeans believe that a more closely integrated Europe will emerge out of the crisis. Monetary union has made the case for fiscal union. And fiscal union will only make the case for political union.

Others note that the EU has never been so unpopular and that the effort to save the single currency is sowing discord and new tensions.

Hopefully, over Christmas and the New Year, there will be a pause. I will take a break from this blog unless events intervene.

To all those who have commented on the blog in the past year: thank you for so many well-judged comments. And whether you have been informed, irritated or entertained - my best wishes for Christmas and the New Year.