Costa Concordia: A sight surreal and disturbing

- Published

Divers have continued to search for people still on board the cruise liner

One of the two scuba divers raises a hammer, and brings it down hard on the ship's window.

He raises his hand again, as high as he can as he bobs in the chilly water. Again, he brings it down fast. The window doesn't budge.

Once the glass was several decks above the water line. Now, it is mostly under the sea.

If they can break in, it is potentially another way to get to any survivors.

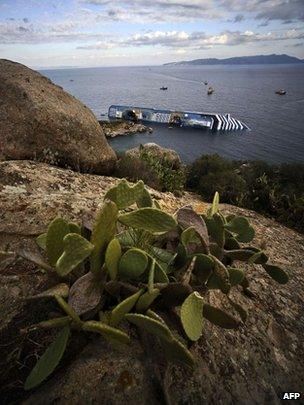

Approaching on a ferry from several miles away you can see the Costa Concordia - its white hulk gleaming in the sunlight beneath the olive-green hills of the Isola del Giglio.

It appears like a giant platform anchored just off the coast.

As you draw closer, it seems to become less real, less plausible - the vast, horrific bulk of the luxury cruise liner just metres from the old port where pastel yellow and blue houses cluster around the seafront.

Look up and there is the bridge, from where the officers and captain would have had a clear view of the enormity of the disaster about to hit them.

Bruised metal

A third of the ship's gleaming windows now forced down at a sharp angle into the water. Everything seemingly turned on its head.

The ship is likely to dominate the view, and the memory of those on Isola del Giglio, for some time

There is the great tear along the Concordia's port hull, where it first ripped across the rocks under the sea.

A boulder is still lodged firmly inside the bruised twisted metal where the water flooded in.

A helicopter flies overhead, hovers a moment, and two more rescuers are winched down on to what used to be the side of the ship. It is now its gently sloping upper deck.

A group pull hard on a rope that dangles down inside.

At the other end is a survivor, who is eventually pulled out and flown to hospital with a broken leg. Many of the rescuers are from the island - volunteers pitching in to help.

Men like Mauro Pretti - who normally runs tourist trips along this beautiful section of the Tuscan coast - are now working round the clock to help out the coastguard.

When the ship ran aground, he was among those on the scene, watching as the liner first listed, then capsized.

"The people opened the school, the church and their homes to help the passengers," he says.

The ship has become an attraction for many who live in this small, tight-knit community.

On land, and trampling down the hillside towards the stricken vessel a group stops for a moment to catch their breath.

"It's a disaster for us, it's incredible what happened," says one woman.

Scarred island

From the rocky outcrop the ship is just metres away. The baseline of the top deck open-air tennis court is now level with the water lapping around the ship.

A table and a satellite receiver dish float alongside the ship.

Sunloungers lie in a heap where they fell against a wall as they slid across the deck.

And it is possible to look right down into the vast yellow funnel which once proudly towered above the entire vessel.

The rescue effort continues. The man in charge, Franceso Paola Tronca, says it is "very difficult and sensitive. We have the same people who worked at [the L'Aquilla earthquake]."

It seems more and more likely that the death toll will increase, perhaps up to 20.

Considering that more than 4,200 people were on board, and that many survivors have complained that, as far as they were concerned, the crew was not prepared for such a disaster, that is perhaps remarkable.

This tiny island though will be scarred - like the victims and their families - for some time to come.

For months, perhaps even years, the view here will be dominated by the luxury dream liner, quietly settling into the seabed.