Putin election victory: What next for Russia?

- Published

Where will 'Putin Mark III' take Russia from here?

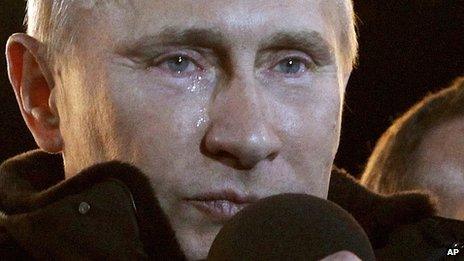

The clearest indication that in the last few months Vladimir Putin was indeed rattled by the implications of Russia's burgeoning opposition movement came on election night on Sunday.

He addressed loyal supporters gathered at his open air victory party in a voice raw with emotion.

Apparently moved to tears, he roared in triumph at the crowd and described the election as a battle for survival against a dangerous foe who had now been vanquished.

So the question now for those watching events in Russia is, with the election over, what is the next step?

Which way will Mr Putin move? Both on internal policy - dealing with the opposition; and externally - how Russia positions itself on key foreign policy questions vis-a-vis the West. Will he be a pussycat or a tiger?

Will he draw the conclusion that he now has a strong new mandate from the Russian people that allows him to relax and show some flexibility?

Or might he feel vindicated by his election win, reinforced in the view that what Russia needs is a strong leader, willing to impose order at home and lash out at foreign enemies (whether real or imagined)?

Fraud evidence

On the home front, much rests on the response from the opposition.

Possibly Mr Putin's room for manoeuvre will be challenged from below if, as happened in December, more and more evidence of fraud trickles out through internet videos and testimony.

Will opposition to Putin continue to build?

Such anecdotal evidence probably won't be enough to undermine his legal victory - no-one seems to think he won less than 50% of the vote.

But it could eat away at his authority if, as in December, it propels outraged citizens on to the streets again to protest in large numbers at an unfair system.

Heavy policing that resulted in crowds being dispersed by riot police and hundreds of detentions at opposition rallies in Moscow and St Petersburg on Monday night could be the sign of more trouble to come.

Maybe the country will revert to the situation of the last few years, where there was little official tolerance for street protests, and any activists who did not stick strictly to what they had been explicitly sanctioned to do would find themselves roughed up and clamped in detention.

The rhetorical groundwork has certainly been laid for a tough response.

Repeatedly Mr Putin has warned that some activists, fuelled by support from abroad, might be trying to fuel public disorder with the aim of sowing the seeds of chaos and bringing down the government.

'Misunderstood liberal'

But there are also already signs of him and his team reaching out at home.

No-one doubts Putin won more than 50% of the vote

Even before the election was over, his spokesman was telling the BBC that Mr Putin was a "misunderstood liberal".

Mr Putin himself was swift to invite all the defeated presidential candidates in for a chat. Only the veteran communist leader Gennady Zyuganov refused the invitation.

Mr Putin pointedly told the young billionaire businessman Mikhail Prokhorov, who polled better than expected among Russia's urban middle class, that he thought they could have a fruitful dialogue about Mr Prokhorov's plan to set up a new political party.

In a separate and potentially highly significant move, his president and soon-to-be prime minister, Dmitry Medvedev, announced he was giving the Russian prosecutor until April to review the case of the jailed oil tycoon, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and look again at the decision not to register one of Russia's small opposition parties.

Of course promises are not yet actions, and there have been cases before when attempts by Mr Medvedev to show flexibility have apparently been vetoed by his boss, Mr Putin.

But some opposition leaders said they were encouraged by this news, and saw it as the direct result of their three-hour chat with President Medvedev earlier in the year.

They said they believed if they could keep up the pressure from below, through street protests etc, it would help those intent on reform inside the system to make their case to Mr Putin.

Iran and Syria

How Mr Putin will decide to position Russia internationally is also interesting.

For months, Russian diplomats have been saying that foreign governments will be pleasantly surprised by Mr Putin once he becomes head of state again: they will not find he is a more difficult interlocutor than the genial but weak Mr Medvedev.

The Russian foreign minister will visit the Arab League in Cairo at the weekend

But the harsh populist language that peppered Mr Putin's speeches during the election campaign do leave open an opposite possibility - that "Putin Mark III" (his third time around as president) will be more not less confrontational, and more intent on showing his core constituency at home that Russia is not a country to be taken for granted or pushed around by Western partners.

Perhaps the two big test cases, and the issues where Western governments are most concerned, are the foreign policy challenges which in recent months have seen Russian vetoes at the United Nations blocking international attempts at exerting pressure - on Iran and on Syria.

Of the two, Syria is probably the more urgent issue. The potential Iran nuclear threat is existential, but still theoretical (just). The humanitarian crisis in Syria is real and immediate.

And on Syria there are interesting signs of Russia's possible engagement with Arab and Western partners.

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov goes to Cairo to join a meeting of the Arab League this weekend. He says he hopes for progress on negotiations to start a national dialogue in Syria.

Russia's bottom line is no foreign intervention (even by humanitarian corridors) and no external demand for regime change (the Syrians must themselves decide, says Moscow).

So the new UN Security Council resolution currently being drafted on Syria is, according to the Russian foreign ministry, still unacceptable.

Support for Assad

But perhaps there is room for manoeuvre. While President Assad stays in control in Damascus, Russia will not abandon its long-time Middle Eastern ally.

But what if his position weakens internally?

"Every country has to be realistic and be prepared to adjust its position," says Alexei Pushkov, the new chairman of the foreign affairs committee in the Russian parliament and Mr Putin's chosen envoy to visit Damascus recently.

Another possible sign of flexibility.

Russia may not be facing revolution. But over the next weeks and months, it faces choices which could determine its future direction.

The indications may be in small subtle moves. But the implications could be enormous.

Do not be fooled into thinking the current drama in Russia is over.

And watch carefully. The devil may be in the detail.