Spain moves to centre of eurozone crisis

- Published

- comments

There is no obvious mechanism to deal with the toxic debt pile in Spanish banks

In the few weeks before the Greeks return to the polls, Spain has taken Greece's place as the epicentre of the eurozone crisis.

Last night the crisis was discussed in a video-conference call between Angela Merkel, Mario Monti, Francois Hollande and Barack Obama. Investors are fleeing to safer havens, however low the return.

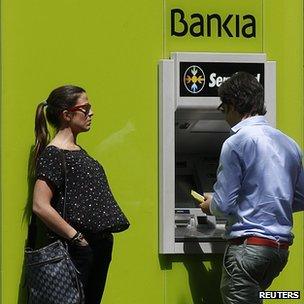

The particular problem is how the Spanish government intends to finance its fourth largest bank, Bankia. It was announced last week that 19bn euros (£15bn; $24bn) will have to be injected into the bank. This uncertainty has driven Spain's borrowing costs to 6.7%.

And beyond Bankia the extent of toxic real estate loans remaining hidden in other banks is still not clear. Estimates put the figure at around 180bn euros, but we won't know the true picture until auditors finish their investigation next month.

The dilemma was summed up by Francis Lun of Hong Kong-based Lyncean Holdings: "The Spanish banks are in trouble because of real estate loans. And the hole is so big that the Spanish government will find it difficult to save the Spanish banks without blowing a big hole in its budget."

And it's not just the hangover from the housing and construction bubble. Some regional governments are struggling to manage their debts and their overspending.

The former Spanish Prime Minister, Felipe Gonzalez, said "we're in a state of total emergency, the worst crisis we have ever lived through."

Grim scenario

The fear that Spain is trapped in a cycle of decline is evident in Brussels. Yesterday the EU's top economics official Olli Rehn offered Spain an extra year , externalto cut its deficit to 3% if it came up with a convincing plan for its budget. Madrid said it did not need the extra time, sensitive about appearing to need outside help.

But the reality is grim. Unemployment, at 24%, is still rising. The country is in recession. The banks have a mountain of debt and real estate prices are still falling.

Spain insists that neither the government nor the banking sector needs a bailout, but elsewhere in Europe that is openly being discussed. And the question is where the funds will come from.

Spain is the eurozone's fourth largest economy. From 1 July the eurozone will have a permanent rescue fund, in the European Stability Mechanism. It can draw on 700bn euros. Even if that were enough to save Spain it could not help Italy, which is being buffeted by the Spanish crisis. Its borrowing costs have gone above 6%.

It potentially raises the question that has hovered over the eurozone for two years. What actually stands behind the single currency? Where is the lender of last resort?

Deputy Prime Minister Soraya Saenz de Santamaria defined it as being nothing less than about the future of Europe. "If the EU doesn't reinforce the eurozone with some sort of mechanism, it's not about who leaves, it's about the EU itself. What is Europe without the euro?"

That will once again put more pressure on Germany, the EU's strongest economy, for if Spain cannot solve its funding problems it will look for a European solution.