'Europe's last dictator' Belarus' Lukashenko opens up

- Published

A rare audience with Belarus' President Alexander Lukashenko

The question came out of nowhere - and it caught the President of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, off guard.

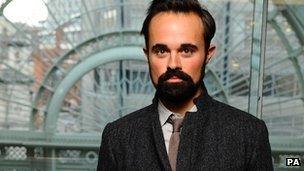

"So, what's your opinion on group sex?" asked Evgeny Lebedev, Britain's youngest newspaper proprietor, who had flown to Minsk to interview the Belarusian leader.

The question, prompted by comments about the merits of group sex made by Russian President Vladimir Putin during a discussion about jailed punk band Pussy Riot, caused Mr Lukashenko to pause for just a fraction of a second, before he shrugged his shoulders and said matter of factly: "I really don't have an opinion on group sex."

It felt as if the room, full of political advisers and camera operators, sighed with relief as the conversation moved to the apparently less awkward issue of human rights abuses.

But the brief exchange on group sex was hardly the only surreal moment in the conversation between the son of a Russian oligarch, once labelled London's latest "It boy", and the man whose iron rule has earned him the title of Europe's last dictator.

Evegeny Lebedev was granted a rare interview with the Belarusian president which lasted many hours

Seated in ornate chairs in front of a faux fireplace, slim Mr Lebedev, dressed in fashionable tight grey jeans and the bulky, plain-speaking president in a dark grey suit made an odd pair.

The four-hour interview touched on many subjects, from democracy and economy, to the fall of the USSR and the war in Iraq, from Mr Lukashenko's friendship with the former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi - "I told Muammar 'beware of Europe!'" the Belarusian president recalled.

Also on the agenda were his seven-year-old son Kolya - who often attends official meeting with him, something Mr Lukashenko claimed was because the boy was so attached to his father that he will not go to sleep without him, not because, as has been claimed, he is being groomed for succession and the human rights abuses that Mr Lukashenko is accused of.

There was even a brief toast with the specially brewed "presidential vodka", although Mr Lukashenko took only a tiny sip, saying he does not handle alcohol well.

BBC as observers

Mr Lukashenko, who has been in power for 18 years, is banned from travelling to the United States and Western Europe. He has been accused of torture and human rights abuses - he has thrown his opponents in prison, banned protests and restricted freedom of expression.

Western journalists rarely get a chance to hold him to account, but Mr Lebedev managed to get the rare opportunity through his personal connections. BBC Newsnight was invited along, but as observers not interviewers.

Mr Lebedev, who hates being called an oligarch, went to Belarus as a journalist for the Independent, the British newspaper, which along with London's Evening Standard newspaper, his father Alexander Lebedev bought for him.

Speaking the night before the interview, Mr Lebedev had said he was determined to ask tough questions, adding: "I am told that apparently the president is ready for a fight".

But the interview never became much of a fight and from his very first answer Mr Lukashenko took firm charge of it.

'Anarchy averted'

Mr Lebedev's father made his billions after the break-up of the Soviet Union, in the chaotic, rapid privatisation of state monopolies that made a handful of Russians rich and left millions in poverty.

Mr Lukashenko never allowed this to happen in Belarus, and he dismissed Mr Lebedev's first question asking whether in the early 1990s Russia chose democracy over fairness, while Belarus went the opposite route:

Lukashenko denied his young son Kolya was being groomed to succeed him as leader one day

"The sort of question you ask makes me wonder: but isn't fairness the very essence of democracy?" Mr Lukashenko said. "I have always believed that genuine democracy is fairness. The basis of my politics is first of all fairness and honesty."

"I would not say what happened in Russia in the 1990s was democracy, it was anarchy, and here you are right, we managed to nip these anarchic tendencies in the bud, we saved the country," he said.

Time and again through the interview, Mr Lukashenko referred to the stability he had brought to the people of Belarus.

"Look outside the window. Do you see the fence outside the palace? Do you see any guards? This is a country where everyone is safe," he said.

But the relative stability of Belarus comes at a price.

There is no presidential term limit here and the 1996 referendum consolidated Mr Lukashenko's power. Not a single election in Belarus has been deemed as free or fair by the West. Not a single opposition candidate won a seat in the recent, parliamentary vote. Protests have been violently supressed.

Saudi Arabia comparison

But every time Mr Lebedev pointed at deficiencies of the Belarusian political system, Mr Lukashenko came back with an articulate and colourful attack on what he described as hypocrisy inherent within Western democracies:

Although freed from jail, opposition journalist Irina Khalip is still unable to travel freely

"Americans want to democratise us. OK, but why not go and democratise Saudi Arabia. Are we anything like Saudi Arabia? No we are far from that. So why aren't they democratising Saudi Arabia? Because they are bastards but they are their bastards," Mr Lukashenko said at one point - adapting Franklin D Roosevelt's famous description of Nicaraguan leader Anastasio Somoza.

"Don't you think you have too much power?" Mr Lebedev asked him.

"Yes it is a lot of power," Mr Lukashenko readily conceded, "but I believed then (in 1996), and many believed then, that we had no choice. We had to save the country, unite around something or someone to survive,"

"Isn't it time to open up now?" Mr Lebedev countered.

"If there wasn't for this insane pressure from you maybe we would, this unnecessary pressure which is trying to separate us from Russia for example. You are having the opposite effect, you are pushing us away from that very process. You don't want any democracy here," Mr Lukashenko replied.

The West's real agenda, the president said, was to open up Belarus' state controlled economy, which would make it vulnerable to the economic problems of the rest of Europe.

Benefits of power

But many disagree with this assessment. Irina Khalip is a Belarusian opposition journalist for Novaya Gazeta, a Russian newspaper also owned by Mr Lebedev's father.

In 2010 Irina and her husband - opposition leader and former presidential candidate Andrei Sannikova - were jailed for organising protests. International pressure got Irina out of jail and from under house arrest, but she is not allowed to leave the city, is visited regularly by the police, often in the middle of the night, and has another trial pending.

Several people have asked Mr Lukashenko about the fate of Irina Khalip before, and yet he looked surprised when Mr Lebedev broached the subject.

Mr Lukashenka said he thought Ms Khalip was already out of the country. He then turned to his aides and told them to send her to Moscow with Mr Lebedev. "Don't bother bringing her back" he added.

Minutes later a memo to that effect arrived. "You see, being dictator isn't such a bad thing," Mr Lukashenko joked handing the memo over to Mr Lebedev.

Later that day Mr Lebedev brought Ms Khalip the news that she could travel again. Irina was visibly grateful, but also sceptical. Mr Lukashenko's Belarus, she explained, can be a dark, secretive place where what is said in public does not necessarily correspond to reality.

Bomb verdict controversy

Take for example the case of the Minsk metro bombing, an explosion that killed 15 people in April of 2011. Within 48 hours, police arrested two young men. Within weeks they were convicted and executed.

A BBC Newsnight investigation in July into the attack raised the possibility that security services were involved in the bombing, and the mother of one of the men said confessions were extracted under torture.

The European Union cristicised the execution of Dmitry Konovalov and Vladislav Kovalyov

Mr Lebedev asked the president whether he had any doubts about the verdict.

"Not a single one," Mr Lukashenko answered firmly. He said that allegations that confessions were extracted under torture were not true. He spoke at length about how international criminologists, including teams from Israel, France and Interpol, backed the result of the investigation, which he said was under his personal control.

"All were unanimous that these were the people who had committed these acts of terrorism," he said.

Although we, the BBC, were present only as observers I told the president about the findings of the Newsnight investigation and Mr Lebedev's own Independent newspaper, which covered the trial extensively, and asked him why the verdict was so rushed.

In response Mr Lukashenko suggested that I watch the footage of the entire trial myself before "jumping to conclusions".

"Are you trying to convince me that I blew myself up?" he said "We have an image of a calm, stable Belarus, which we don't want to lose. The worst thing for us is to lose that. Are we such idiots that we would have planted and detonated the bomb ourselves?"

Ongoing fight

After the interview, the president put his arm through Mr Lebedev's and the two men disappeared for a private meeting. Mr Lebedev later told me he came to Minsk with a message from somebody in Europe, but refused to elaborate.

When I caught up with him afterwards Mr Lebedev sounded pleased with the interview, and seemed genuinely surprised when I asked him why he spent so much time debating with Mr Lukashenko on the perils of Western democracy instead of challenging him on problems in Belarus. Or why he chose to grill him on failure to rename the KGB, but not on torture that it is accused of.

"I did challenge him," Mr Lebedev replied,"... and I managed to get Irina Khalip out".

But back at her house Ms Khalip said she has nothing to celebrate yet:

"Lukashenko made a promise to Yevgeny Lebedev, he didn't say it to the criminal police who are looking after me. Words don't have legal meaning. We need a piece of paper with a signature and a stamp - even in a totalitarian state," she said.

And even if Mr Lukashenko keeps his promise, she does not want to leave Minsk. This is her home. Like so many others, Ms Khalip wants to find her freedom in Belarus.

- Published30 July 2012

- Published13 April 2011

- Published16 May 2011

- Published14 May 2011

- Published27 January