Stalemate in 'ungovernable' Italy after elections

- Published

The votes have been counted, but Italians may soon be returning to the polling stations

The result was widely feared and predicted - that no party or coalition would be able to govern the country. Italy faces a period of political deadlock. The headlines cry "ungovernable" and "paralysis".

The leader of the centre-left, Pier Luigi Bersani, said: "It is clear to everyone that this is a very delicate situation for the country."

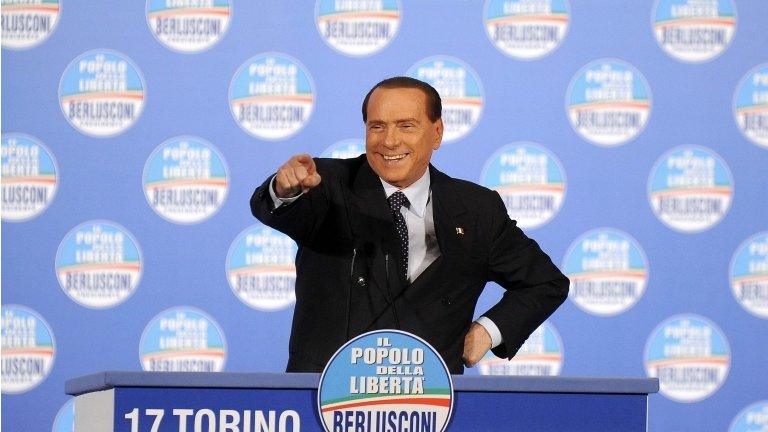

The centre-left won the lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, with a wafer-thin margin of the nationwide vote. But a majority is needed in both chambers to form a government. In the Senate, Silvio Berlusconi and his centre-right allies have performed better.

The landscape is further complicated by the extraordinary success of the protest movement of Beppe Grillo. One in four voters backed a movement that has promised to shake up and kick out Italy's political establishment.

Mr Grillo has tapped into a mood of anger and resentment. He never gave a single interview to Italian TV and yet has nearly 170 seats.

The country is in deep recession. Unemployment is rising and industrial production is at its lowest level since the 1990s.

Mr Grillo raged against corruption, against budget cuts, against austerity and promised to hold a referendum on continued membership of the euro.

He promised "a tsunami" and he delivered. His MPs are young, unproven and without political experience.

The horse-trading will now begin. Pier Luigi Bersani has enough votes to dominate the lower house. That is not the case in the Senate. Even if he were to join forces with the former Prime Minister Mario Monti he would not be able to command a majority there.

He may try to operate a minority government but that will clearly be unstable. There may be an attempt to form a wider coalition to govern the country at a time of economic crisis but it is unlikely to survive the summer.

One unanswered question is whether Beppe Grillo will be open to a deal. Would his movement support, say, a centre-left coalition in exchange for widespread reforms of the political system? We don't know. Buoyed up by success he has only promised to clear out the political class.

Sooner rather than later the country will hold another election.

This vote was not just a massive rejection of politics as it is played in Italy.

It was also a rejection of the policies championed by Mario Monti, the unelected prime minister who replaced Silvio Berlusconi.

He was widely praised in Brussels for bringing stability to Italy but his austerity measures are blamed for deepening the recession. He was a major loser in this campaign. Europe's leaders feted Mr Monti but the people did not. This vote was a rejection of the austerity being pursued by Brussels to save the single currency.

On the campaign trail leaders from both right and left hit out at the power of Germany. In Naples last week a leftist leader shouted "go show Angela Merkel it is not a German Europe".

More than half of those who voted supported parties that had been openly critical of Germany's policies for the rest of Europe.

So the markets will have to digest not just instability in the third largest economy in the eurozone but a mood which rejects policies which are seen as driving Italy deeper into recession.

- Published22 February 2013

- Published22 February 2013

- Published21 February 2013

- Published27 April 2013

- Published18 February 2013