Italian election lessons for wider Europe

- Published

Many Italians have lost faith in politicians

A week ago I was outside polling stations in Rome asking people how they voted.

Many were coy. Others openly said they had voted for Beppe Grillo.

These were ordinary, thoughtful people. They had not been emotionally swayed by a firebrand speech in a piazza. Neither did they appear unstable.

They had made a clear calculation: that Italy's political system needed tearing up and cleaning out. They cast their vote for Mr Grillo's movement because they had lost faith in the old political caste.

In Brussels, there was silence or the knee-jerk rant against populists or clowns.

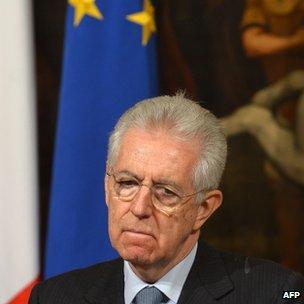

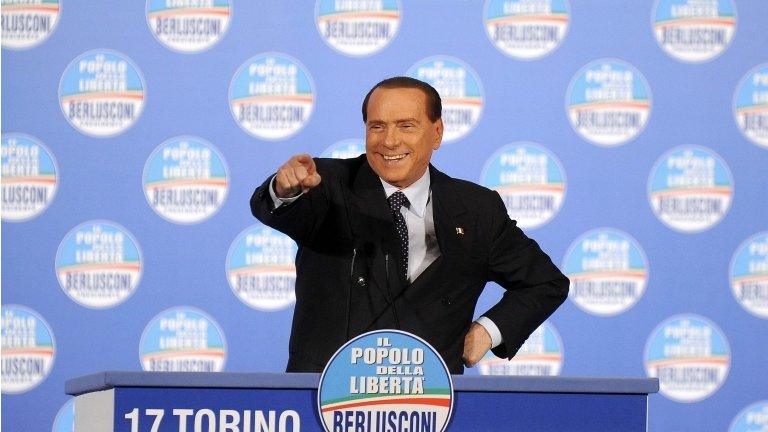

Mario Monti was the darling in Brussels and Berlin, but Italian voters rejected him

What there was not was an understanding of the desire for fundamental change, or of the growing despair that Europe is not working.

Mr Grillo is full of flaws and risks and contradictions but he understood the disaffection and rage coursing through not just Italy but much of southern Europe.

'Failing' prescriptions

In this election Brussels and Berlin had a candidate. He was Mario Monti.

At the end of last year - when it was apparent that Italy was going to the polls - European officials queued up to shower Mr Monti with praise. No-one was in any doubt he was the anointed one.

Yet he was rejected. It was not enough that he had ushered in some stability and embraced reforms.

He had taken on the pension system, tax evaders, the closed professions whilst raising taxes and cutting the deficit.

It counted for little because many Italians have lost faith. They are enduring the worst recession in living memory.

Consumer confidence and industrial production have fallen to the lowest levels since records began.

Italians have been hit hard by the government's austerity measures

Higher taxes have stunted demand. Many believe, quite simply, the European prescriptions are not working.

South v North

And so during the campaign the fingers pointed at Germany.

I heard candidates from both the right and the left use similar words: "Go show Angela Merkel, it is not a German Europe."

Ironically, Mario Monti - on several occasions - had warned Chancellor Merkel about the danger of a sullen southern Europe turning against the north.

It is also the case that the eurozone crisis is undermining established politicians.

Increasingly, on critical issue, national politicians defer to Brussels and so raise the question as to why vote for them.

During an interview with Pier Luigi Bersani, I asked about his plans for growth. He indicated they would depend on decisions taken at a European level.

During the French campaign Francois Hollande, rather like Bersani, had said "austerity was not the only option".

Mr Hollande promised that his first trip would be to confirm to Angela Merkel that the "French have voted for a different kind of Europe".

But in office he has struggled to deliver. French economic policy is hemmed in by a fiscal pact where deficit targets are set in Brussels. All the French can do is to hope the Commission grants them some flexibility.

Ticking clock

To those without jobs or feeling economically insecure the established politicians can appear powerless and, not surprisingly, the voters turn elsewhere.

Those who declare the eurozone crisis over are missing what is happening in a raft of countries.

Unemployment - still growing and not seen at such levels in Europe since the 1930s.

The emigration of tens of thousands of graduates: 300,000 from Spain alone. Many never to return.

The soup kitchens. The aching poverty. The suicides. Much of it underreported.

And herein lies the most dangerous question for Europe's leaders. Could austerity, the deficit cutting, end up destroying European unity?

As Martin Woolf wrote in the Financial Times this week: "I wonder whether the eurozone will survive its cure."

The questions are fundamental.

Say the Germans and their Brussels allies have calculated incorrectly.

Say cutting deficits and embracing structural reforms does not revive the European economies.

Say austerity damages output more than expected.

Say people begin questioning whether the need to reduce the divisions between the eurozone economies has ushered in a European "Great Depression".

Then all bets are off. And that was the view of a very senior European official who I spoke to in December. Two years is all we've got, he said, to deliver.

The lesson of the Italian elections is that the clock is ticking.

- Published22 February 2013

- Published22 February 2013

- Published21 February 2013

- Published27 April 2013

- Published18 February 2013