Kurdish mothers 'can't lose hope' for peace

- Published

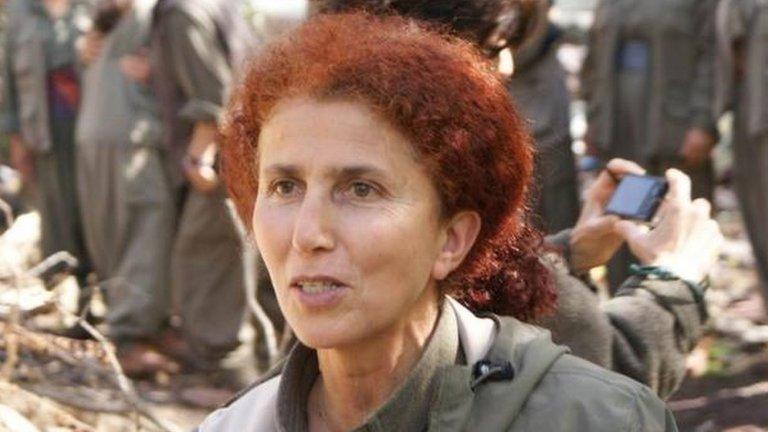

Adile Samur's daughter left home to join the PKK four years ago, aged 18

As the leader of the PKK declares a ceasefire, there are hopes it will pave the way for an end to its three-decade conflict with Turkey.

One mother, Adile Samur, tells the BBC's James Reynolds in Istanbul how she hopes this would allow her children, all PKK members, to return home - but not without an "honourable" peace.

I come from a small Kurdish village called Suruc, near the border with Syria. My family isn't rich. A decade ago, we moved here to Istanbul because there were no jobs for us back home.

My husband now runs a small kiosk in a shanty area in Istanbul. We have seven children. We managed to send them to primary school, but after that they had to look for work. Three of our children have joined the PKK [Kurdistan Workers' Party]. None of them gave me any warning, but that's how it is.

My daughter joined up four years ago when she was only 18. My family in Suruc managed to get me a photograph of her. But I don't know exactly where she is at the moment - she could be in Turkey or in Northern Iraq [the main PKK base].

I haven't heard from either of my boys since they left. The first went up to the mountains three years ago, when he was 20.

'Devilish person'

Then, just six months ago, the other one joined up. He's 26 years old and had never planned to join the PKK.

But then he was jailed for six months. A judge ruled that he'd made "cryptic" remarks during a phone conversation with a friend.

Just one phone conversation - and he was jailed for six months! My son said that he was tortured during his time in prison. I wanted to see the marks on his body - but he refused to show me.

The last day I saw him, I was in the backyard. He was wearing green shorts and asked me to make tea for him. Then we sat down. He laid on the couch, put his head on my chest and said how comfortable it was. I remember that day so clearly. Then he was gone. He wouldn't have joined up unless he'd been tortured.

From time to time the Turkish police still knock on my door and ask me "Where is your son?" I say, "I don't know, you very well know where he is."

They call me a bad mother, a devilish person, for not knowing where my son is and threaten me that sooner or later they'll get him. I don't care what they say.

'Honourable peace'

The PKK contains one of the largest contingents of armed women militants in the world

I hope I will be able to see my sons and my daughter again. I can't lose hope. Over the last 40 years, thousands of young men and women have gone up to the mountains - their mothers are waiting for them to return.

They need to bring with them an honourable peace. They went up to the mountains in order to fight for peace and democracy - for the recognition of culture, identity, and language.

But our children can't come back empty-handed. If they just come back for the sake of it then I will not accept their return. My head is held high because my children want the right thing. But if they come back empty-handed then I won't be able to hold up my head and look others in the eye.

For 40 years, there has been a war in this country. People have been killed, or forced to migrate from their homes. There are mothers who are trying to find their children's bones. There needs to be justice for them.

I hope that [PKK leader] Abdullah Ocalan is released from prison and that he gets elected to parliament. I don't know how to read and write but I watch TV. The MPs who've visited him say that he is healthy and in good shape.

This time I believe there's hope for peace. I can't lose hope. I don't want any mothers to cry after their children any more. Neither the mothers of the Kurdish guerrillas nor the mothers of the Turkish soldiers. This should end.

- Published18 March 2013

- Published13 March 2013

- Published10 January 2013

- Published4 November 2016