Putins' divorce throws spotlight on 'first lady' role

- Published

Russian President Vladimir Putin and his wife Lyudmila after his inauguration in 2012

The announcement that Russian President Vladimir Putin and his wife Lyudmila are to divorce came after months of speculation in the Russian media over Mrs Putin's near-invisibility.

Lyudmila Putin had long shunned the limelight, and in the last few years her public appearances had become increasingly rare. Before the joint TV appearance at which the couple announced that their marriage was over, Mrs Putin was last seen at her husband's side on Russian television when she attended his inauguration as president in May 2012.

Invisible "first ladies" were the norm during the Soviet era, when secretive leaders preferred to keep their wives and families out of sight.

The phenomenon of Raisa Gorbachev appeared to represent a break with this tradition. At a time when her husband was breaking the mould of Soviet politics, the impeccably dressed and eloquent Raisa was overturning notions of how a typical Soviet first lady should look and behave.

Raisa and Mikhail Gorbachev in 1989 - changing the Soviet image

However, though Raisa quickly became the darling of the Western media, she was disliked by many back home - for exactly the qualities which made her popular abroad. In fancy, bespoke outfits and often in the media spotlight, Raisa's image contrasted with the tough reality of her crumbling communist country.

Naina Yeltsin, the wife of Russia's first post-Soviet president, was less flamboyant than her predecessor, but still had a distinctive image and voice.

But with the dawning of the Putin era in Russian politics, there appears to have been a return to the camera-shy image of presidential wives in the Slavic-majority states.

Lyudmila Putin's low profile was in marked contrast to the global role played by her husband as president of Russia.

She did recently feature on the cover of a glossy magazine. But the three-times first lady was seen in public so rarely that her appearance at an awards ceremony in late March - her first since last year's inauguration ceremony - caused quite a stir in the Russian media.

One Russian independent journalist, Mikhail Fishman, went so far as to say that Mrs Putin's presence "equals zero". He suggested that having a family can help a ruler to be seen as open and down-to-earth, but that President Putin, an "authoritarian monarch", prefers to be viewed as aloof and God-like.

Disappearing act

What about other post-Soviet first-ladies?

Ukraine's Lyudmila Yanukovych - wife of the president - is almost as invisible.

Reports say the first lady is living as a recluse in Donetsk, the stronghold of her husband's party, making rare appearances at regional events, and is almost never seen in Kiev.

Ukraine's first lady is remembered for her speech scorning the Orange Revolution leaders

Even before Viktor Yanukovych was elected president in 2010, she had vanished from the public eye.

Her most memorable public speech was made at a rally during the Orange Revolution in 2004, when her husband, the then prime minister, was vying for the presidential job.

Her beret awry and language clumsy, she accused the rival pro-Western camp of supplying their supporters with US-made felt boots and drug-laced oranges. The remarks were so extreme that they are still remembered, and ridiculed, almost a decade on.

The embarrassment caused by that speech is the likely reason for her disappearance, suggests a prominent Ukrainian journalist, Sergei Leshchenko.

He adds that the "first lady" concept - a feature of US politics - has not taken root in the former Soviet republics, because most of their leaders were born and raised in the USSR and share its mindset.

First son

Belarusian expert Valeriy Karbalevich says the Soviet tradition of "not putting the wives of leaders on display" is deeply rooted in the public consciousness.

Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus is frequently accompanied by his youngest son Nikolai

In Belarus, ruled in authoritarian Soviet-era style, there is no first lady. President Alexander Lukashenko has in recent years been accompanied even at official ceremonies by his young son Nikolai.

The boy attended his father's inauguration and accompanied him on numerous foreign visits, most recently to Venezuela to pay last respects to the country's populist leader, the late Hugo Chavez.

The fair-haired and neatly attired Nikolai, never uttering a word by his father's side, could almost be seen as a replacement for the first lady.

Mr Lukashenko is now often seen in the company of women much younger than himself, opposition websites claim.

Eastern paradox

Paradoxically the first ladies in Central Asia, a region considered patriarchal and conservative, enjoy rather more prominence.

Tatyana Karimova of Uzbekistan is eclipsed by her controversial, jet-setting elder daughter Gulnara in the media. But Tatyana engages in what is presented as charity work, and accompanies her husband, President Islam Karimov, on visits.

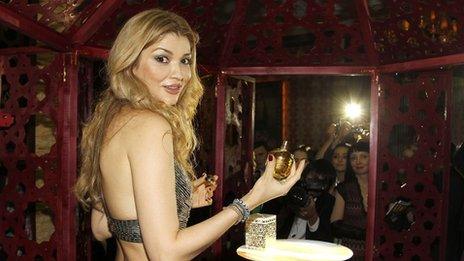

Azerbaijan's Mehriban Aliyeva is said to be more popular than her husband

President Karimov holds Uzbekistan in an iron grip, smothering any dissent, and this publicity for his family serves to underline their clan power.

In neighbouring Kazakhstan first lady Sara Nazarbayeva, according to her official biography, has for many years been overseeing several charitable projects and is the author of six books.

Azerbaijan's Mehriban Aliyeva, a dazzling fashionista, is arguably the most prominent among the eastern first ladies. With her hand in a variety of cultural and "charitable" programmes she has arguably overshadowed her husband, President Ilham Aliyev.

But the ruling family's image is carefully managed and human rights groups accuse the authorities of stifling democracy and jailing dissidents. Azerbaijan also gets a poor rating in the corruption index compiled by Transparency International.

Trained as a doctor and now an MP, Mrs Aliyeva is active in the ruling New Azerbaijan Party. A few years ago, there was much talk that she could succeed her spouse in 2013, but the speculation has now subsided.

Wikileaks cables have revealed the first lady in a less flattering light, as seen by Western journalists. But with the media in her country tightly controlled, Mrs Aliyeva can still enjoy a high profile unperturbed, whatever the allegations swirling around her.

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. For more reports from BBC Monitoring, click here. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

- Published6 June 2013

- Published17 March 2024

- Published27 November 2012