Spy game: A familiar tale continues

- Published

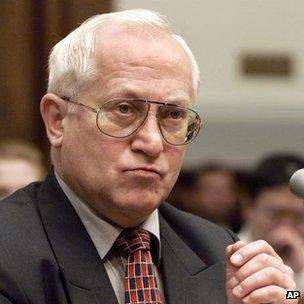

Greville Wynne was sentenced after a short trial in Moscow in 1963

Fifty years ago - nearly to the day - a British businessman stood in a stiflingly hot Moscow court room. Greville Wynne stood accused of being a spy.

He had been a key contact for a Russian military intelligence officer named Col Oleg Penkovsky, who had provided vital intelligence at a time of great tension during the Cold War.

Penkovsky was run jointly by a team of CIA and MI6 officers with the initial meetings taking place at a London hotel, but contacting him in Moscow and passing information proved hard, dangerous work.

At an embassy reception, a young CIA officer named Hugh Montgomery had to climb precariously on top of a sink which then came away from the wall in order to retrieve a message Penkovsky had left in the toilet cistern.

In a Moscow park, Penkovsky also passed packets of sweets (with camera film hidden inside) to the wife of a British MI6 officer while she was pushing her children in a pram.

And another CIA officer was later sent to clear a "drop" in an apartment block where a message was supposed to have been left by Penkovsky.

When he reached behind a radiator for a matchbox containing the message, he was pounced on and detained by the KGB. He, along with Montgomery and others, was expelled.

Col Gordievsky had to be smuggled out Russia in an MI6 officer's car

Wynne was arrested and sent to jail until he was swapped for a KGB spy arrested in London.

Penkovsky himself paid the ultimate price and was executed.

'Moscow Rules'

One of the lessons of the Penkovsky case was that running agents in Moscow was extremely hard for Western intelligence services.

It required what were known as "Moscow Rules" - the closest attention to detail and to what is known in the spy-world as "tradecraft" to avoid being caught.

When Britain's MI6 recruited KGB Col Oleg Gordievsky in the 1970s in Denmark, they were careful not to try to meet him regularly in Moscow for fear of exposing him and leaving him to the fate of Penkovsky.

In the end when the KGB finally caught on to him, he had to be smuggled out of Russia in the boot of an MI6 officer's car in one of the most daring operations of the Cold War.

The Cold War is, of course, over. But spying is not. Each side still wants to know about the other's secrets.

What is Moscow really thinking and doing about Syria or Iran, for instance? And where are Russia's spies hidden within the West?

The former type of information might be known by a diplomat - the latter only by another spy.

And the Russians, of course, want information on British and American politics, defence assets and wider industry (especially high-tech) as well as its spies.

Video footage and photographs have emerged of the man's alleged detention, the BBC's Steve Rosenberg reports

Britain's MI5 has complained about the activities of Russian spies in the UK, saying the numbers are close to Cold War levels - although many will be looking at the large number of Russian exiles.

And America's FBI in 2010 exposed a Russian spy ring living under deep cover, including Anna Chapman, which was thought to be gathering political information.

Political messages

It would be naive to think this was a one-way street, and that the US (and Britain) did not still try and spy on Russia.

MI6 was famously accused of deploying a "spy rock" in a Moscow park in 2006 in which a transmitter to pass information was concealed (meaning there was less need for the kind of furtive exchange that got Penkovsky into trouble).

Much like this latest incident, British diplomats were named by the Russians and exposed on TV.

There is an element of theatrics in the way it is portrayed: the way an agent kicked the rock to check it was working or the display of the wig the alleged CIA man was wearing.

It is designed to embarrass and show up the amateurishness of the other side - one spy service showing it has one up on its opponent and that opponent, no doubt, now keen to get its own back.

There are political messages as well.

Moscow has often emphasised that foreign spies are hard at work trying to "subvert" the country and the government (something they particularly used to accuse the British of doing right back to the aftermath of 1917), and exposing spies provides ammunition for that claim.

The arrest of alleged CIA spies harks back both to a Cold War sense of an external danger as well a sense of Russia still being a country the CIA wants to spy on - like it did in the old days when the US and Russia were seen (often wrongly) as evenly matched.

The "spy rock" scandal severely strained British-Russian relations

It provides a kind of importance and familiarity.

Everyone has read John le Carre and knows how these things work. And it is a lot less complicated and easier to understand than some of the more complex security threats and relationships of the modern world.

Fifty years ago Greville Wynne was put on trial.

Eight years later in 1971, Britain threw out more than 100 Russian diplomats in a very public effort to try to put a lid on their activities.

In 2006, British diplomats were embarrassed by the spy rock scandal, and in 2010, Anna Chapman and others were swapped for individuals who had been accused by Russia of being spies.

Each time, the spying continued. And make no mistake, it will do this time as well.

- Published14 May 2013

- Published13 April 2013

- Published30 June 2011