My Germany: Student fencer

- Published

Nils Hempel explains why he and his fellow students want to duel

Ahead of the federal elections in Germany, the BBC talks to people from different backgrounds about their lives there. In the first in the series, those at the privileged end of society talk about their student fraternity.

Nils Hempel, 26, values his friends as much as any man but perhaps never more than when he is slashing at their faces with a sword.

A law student at Humboldt University from Bremen, he belongs to one of Germany's oldest all-male college fraternities, the Corps Marchia Berlin, in the German capital's well-heeled suburb of Dahlem.

Life there revolves around the fencing match or mensur (literally the prescribed distance between swordsmen).

Closer to a duel than sport, this involves razor-sharp blades, and is held in the presence of seconds (trusted attendants). A doctor is on hand to stitch up the facial wounds, which will scar into badges of honour. Mr Hempel himself has two scars, concealed by his hair.

Dating from the Napoleonic wars, it is still an affair of the utmost secrecy. It is one few outsiders may witness and none are permitted to record.

The mensur is not about winning but the ability to endure without flinching or recoiling, under the unforgiving eye of an umpire. That is no easy matter, to judge by the ferocity of the training we were allowed to film where, adrenalin pumping, the fencers clashed like stags locking horns.

Yet the protective gear the student fencers don on the day - think chainmail and steel goggles - means the fights are possibly no more dangerous than boxing.

The mensur is more than some anachronistic extreme sport. These young men who fight also swear by each other as friends. Recalling why he decided to apply for the corps, Mr Hempel says: "I met these people, we got on splendidly, I liked the community and the sense of belonging."

Fellow member Constantin Weber, from Dortmund, says he joined because his diplomat father had been posted abroad and, finding himself studying in Berlin without his parents nearby, he had sought the friendship and peer connections offered by the Corps Marchia.

Members often live together in the corps house, or return there daily from student digs, to train, dine together and drink beer. Marathon weekend motor crawls around Germany to visit other corps are not unknown.

Mr Hempel is a proud member of the Corps Marchia Berlin where the Latin motto translates as "The strong man despises death"

After they graduate, members retain a strong bond, contributing to the upkeep of their corps, and regularly revisiting the old house and its taproom, of course.

More than one coffin lid has closed over the body of an old corps alumnus decked out in the fraternity cap and ribbon sash of his youth.

It gives them a lifelong connection. But does anyone else in Germany care?

'Movers and shakers'

Mention the fencing and other students may roll their eyes and dismiss it as a posh boy's blood sport. Others would be surprised to know it goes on at all in a country sensitive about all things martial. Sometimes hostility can degenerate into attacks by vandals on corps houses.

The student fencers themselves would be the first to admit that they largely come from "good families" but it would be wrong to dismiss them as an upper-class clique.

Young men of humble background also pass the mensur test to enter one of the 160 or so corps scattered across some 50 universities in the German-speaking world.

Altogether, there are some 3,500 active members of corps in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, and at least 21,000 alumni.

A member born in the economically deprived former East Germany may happily cross schlaegers today with wealthy Bavarians or Swabians.

They are tested by the sword but also on their character, with the emphasis on aspiration and esprit de corps. "We look for movers and shakers," in the words of one corps member.

"Some people regard honour as an old-fashioned term," says Albrecht Fehlig, spokesman for the Student Corps Associations.

"We see it in close relationship with human dignity. Corps students are obliged to respect the dignity of other persons and not to tolerate a violation of their own dignity. This has a significant effect on our social life and contributes to the unique atmosphere of a corps house."

The 17 students who make up the Marchia men are accomplished dancers, too, they tell me. The highlight of the year is a foundation ball in November when, according to Mr Hempel, it is the women who cannot keep up with the men.

After meeting the Marchia, replete with a simple but excellent meal cooked by two of the fencers, I come away with the impression of courteous, good-humoured, sophisticated young men who enjoyed each other's company and treasured the 200-year-old traditions of their house.

Germany and beyond

Corps members hold a vision of Germany as a centre of academic excellence and good fellowship going back to the Middle Ages, when students formed corporations at universities such as Jena.

Fencing had a practical purpose during periods of turmoil such as the wars of the Reformation, when students might band together for self-defence.

Current members are at pains to point out the Nazis despised the corps, which epitomised the old German establishment for them. Five corps were forced to close in the 1930s when they refused to disown members with Jewish connections. Most other corps were eventually dissolved under Hitler.

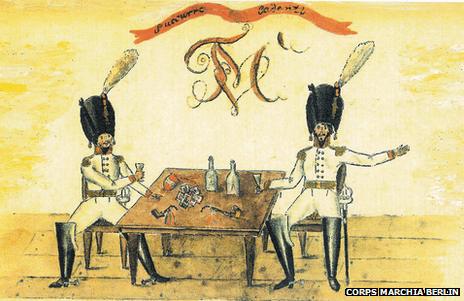

This old picture depicts early members of what is now the Corps Marchia Berlin

Whatever the politics of corps members, they do not come over as German nationalists. The Student Corps Associations should not be confused with other fraternities such as the Burschenschaften, which became embroiled in a race scandal two years ago.

The nationalities of members I met spanned the eurozone states: an Italian, a Spaniard, a Belgian and a Frenchman.

Mr Hempel spoke of an African member from a different corps whose colour was not the issue. What other members resented, he said, was his great stature and ability to clobber shorter fencing partners. There are Muslim members too - not everyone takes the beer.

"Corps are the oldest existing kind of student fraternities in Central Europe," says Mr Fehlig. "We call ourselves the original ones because we see all other kinds of student fraternities as reform movements who tried to bring new aspects - politics, religion, sports, music - into student life, which the corps did not accept."

Bonds are forged that endure as these young blades - who range from lawyers to engineers, from historians to physicists - move into the world of work and family life.

Corps members may make up just a few per cent of Germany's student population but their alumni are over-represented among CEOs of the country's companies.

The scar on the face is the obvious clue for recognising old corps men. Another dead giveaway, perhaps, may be an appetite for tough negotiation, whetted in the mensur.

Filming by Samuel Girona