My Germany: Spanish expatriate

- Published

Spanish expatriate Helena Barcos spoke to the BBC about her new life in Cologne

Ahead of the federal elections in Germany, the BBC talks to people from different backgrounds about their lives there. In the second in the series, we look at Spanish expatriates who have immigrated in search of work.

Helena Barcos, 28, is one of the lucky ones among a new generation from the EU's Mediterranean states heading to Germany.

The woman from Seville has a job as a business processes manager at DHL in Bonn and lives in Cologne, a big student city with a cosmopolitan outlook and one of the most popular destinations for young migrants from her country.

Her secret? Good planning: equipped with a master's degree in business administration, she had secured a contract with a company in Germany as an internee before her arrival, and learnt the language during her internship. She appears to have moved smoothly into the German world of work since her arrival in 2011.

Others less organised can find themselves struggling soon after making the trip north.

One owner of a Spanish-themed restaurant in Cologne says he has Spaniards knocking on his door almost every other day, asking for work.

"Many of these people have good degrees," he continues. "Just yesterday I had a teacher from Castellon asking to work in the kitchen as a dishwasher."

As it happens, the same restaurateur has had a Spanish engineering student washing his dishes for the past three months for eight euros (£6.70; $10.50) an hour. He is heading home to complete his degree but has signed a contract to resume his work at the sink when he finishes in February. "He can find nothing better in Spain," his employer says.

Two other employees in the kitchen are Portuguese nationals who had been working on building sites back home for 350-400 euros a month, the owner adds. "Here they make quite a lot more money."

New faces

Germany saw a first wave of Mediterranean migrants in the 1960s and 1970s, when the factory jobs on offer were perhaps even harder and there was little in the way of community support outside the Catholic Church and social clubs.

Pamplona man Jose Gayarre has done much in recent years to help new expatriates to avoid the kind of isolation many of their forebears experienced.

Saturdays see him organising football matches and barbecues on the east bank of the Rhine in Cologne for the local Spanish community and others. "Only the rain keeps them away!" he jokes.

The freelance editor, who moved to Germany in 1999 not because of any economic crisis but simply to "be a little bit more European", set up a Spanish-language internet radio station in Cologne, which has since grown into a website called Destino Alemania (Destination Germany).

Staffed by volunteers, the site reaches out through social media to offer advice about employment, education and accommodation in Germany, while celebrating local expatriates.

The "Make it in Germany" guide gives official advice to prospective migrants from other EU member-states

"There is a new generation of immigrants here and these immigrants are not going to live in a parallel society - they are coming to stay here," he says.

People from all walks in life are now migrating from Spain to Germany, drawn by German government advertising campaigns such as The Job Of My Life, external, which exhort people to "make it in Germany".

"In Spain you have no chance for work if you are in the construction industry, or an engineer or a doctor," Mr Gayarre says.

There is a wrong way and a right way to go about emigrating to Germany, he suggests. "The difference is [between coming] into a pre-arranged job from Spain or if you come to look for a job, if you know German or if you don't. You have first to learn to communicate, then work."

The temptation is to go for easy jobs like catering, he says, but you are unlikely to learn much German doing those. Possibly the worst scenario, he says, is to arrive in Germany and attempt to live off your savings, waiting for an opportunity.

Fitting in

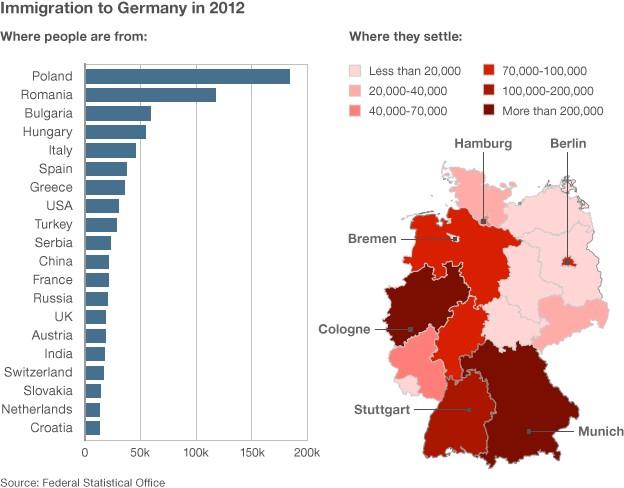

Spaniards tend to go to the former West Germany, regions such as the Ruhr and Baden-Wuerttemberg, cities like Duesseldorf and Cologne, because of the availability of jobs and links established by previous migrants.

While seeking to interview voters ahead of the German election this month in cities as diverse as Wuppertal, Hannover and Berlin, I was surprised by the number of people who turned out to be Spaniards and Italians.

Immigration has been pretty well absent from the 2013 election campaign, not featuring in the debate between the two main candidates to lead the country. The main far-right party plays the anti-immigrant card but gets a tiny following.

While Spaniards generally do not encounter much hostility from Germans, Mr Gayarre says, it can be more difficult for them to make contact with local people in the former East Germany and in rural areas.

He sympathises with those who feel they have no choice but to leave Spain in search of work but believes that the new migration can be a positive thing, encouraging Spaniards to move around the EU, learning new languages and exploring different cultures.

Asked if Spaniards and Germans get on, he jokes: "It's not scientific, and just my own opinion, but a Spanish guy with a German girl, that doesn't work - a German guy with a Spanish girl, that works!"

He takes evident pride in saying that, on the basis of university results, the children of the previous generation of Spanish expatriates in Germany are the best integrated of the Mediterranean migrants.

The late parents of Rogelio Calleja, a doctor from Hannover, came to Germany in the 1960s from Extremadura in search of work.

They got jobs in a sweet factory where they "worked hard, really hard, honestly and hard", he says, but they found it very difficult to integrate into German society because of the language gap. Education closed that gap for their children.

Asked if he feels German or Spanish, the child of the first migration says: "I feel European. We in Europe are a big family."

Additional filming by Samuel Girona

The first part of this series looked at the student fencing fraternities out of which many of Germany's business elite emerge