Roma case in Greece raises child concerns

- Published

Police in 190 countries have been asked to check Maria's DNA

The high-profile case a young girl in Greece has highlighted the treatment of children in Roma communities across Europe.

DNA tests conducted in central Greece on a blonde-haired girl known as Maria have shown that the couple looking after her were not her biological parents.

Tests were also carried out on a girl taken into care in Dublin, although they have concluded that she was living with her biological parents. Police had initially not been persuaded by the birth certificate and passport provided by the family, reports said.

Both stories, one on the western fringes of Europe and the other in the east, involve blonde-haired girls with disputed documents.

"Not all Roma communities have dark skin: there are Roma who have light skin and green eyes," says Dezideriu Gergely, head of the Budapest-based European Roma Rights Centre.

He is concerned about the dangers of racial profiling and insists Maria's case in Greece should be viewed as unusual. While it is not uncommon for children to be raised by extended families, for example by grandparents, Mr Gergely considers it rare for children to be brought up beyond their biological families.

"Definitely there is a need for an answer. Something was not right and that is for the court to investigate." What alarms him is the labelling of an entire community.

There has been widespread interest in Maria, particularly because of the high-profile disappearances of two British blonde-haired children: Madeleine McCann in Portugal in 2007 and Ben Needham on the Greek island of Kos in 1991.

Indeed, the authorities have themselves internationalised the story with Interpol asking 190 countries, external to check for a possible match to Maria's DNA, to assess whether she has been a victim of child abduction or trafficking.

Mr Gergely believes the latest cases may resurrect old hatreds and myths of babies being stolen. Roma in already-marginalised communities such as Serbia have complained of racial discrimination. But he does acknowledge that the Roma may have been exposed to child traffickers.

Greek prosecutors are looking at birth records across the country

"It's true the Roma are a vulnerable group because of extreme poverty, low income and low levels of education. But it's not related to cultural factors or to do with the Roma community, let's say, getting involved in trafficking."

The UN children's agency Unicef has told the BBC that Roma communities are often used by traffickers because they are seen as "under the radar of society".

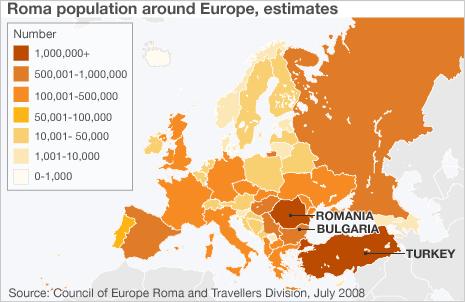

As many as 3,000 children in Greece are in the hands of child-trafficking rings originating in Bulgaria, Romania and other Balkan countries, Unicef says.

Most cases are not thought to involve abduction but rather the buying and selling of children for a few thousand euros.

Part of the problem in Greece appears to lie in its localised and out-of-date child-registration system. And yet, ever since the mid-1990s, the European Union has tried to ensure all Roma communities across Europe are fully registered.

Most Roma, some 95%, are in settled communities in the EU and both Maria's case and that of the girl in the Tallaght suburb of Dublin involve settled families. In other words, there is no obvious need for paperwork problems.

But for all the efforts to bring Roma families into national databases, many are still clearly beyond the system.

The couple who registered Maria, according to the Greek authorities, used false identification and claimed to have had six children in under 10 months. And Greece's supreme court has called for an urgent investigation across the country into birth certificates issued since 2008.

The prosecutor's order warns that Maria's case may not be unique. "This could have happened in other parts of the country," it warns.

In Ireland, too, there are concerns about the registration system, which have alarmed Siobhan Curran, Roma project co-ordinator at the Pavee Point travellers and Roma centre.

She has seen many in Ireland's 5,000 Roma population struggle to get hold of social benefits because of what she sees as "very harsh criteria" needed to meet what is known as the habitual residence condition, external. Poor literacy and language can also be a problem for Roma looking for a job when they try to register for the Personal Public Service number (PPS), required for tax purposes.

She describes a vicious cycle where families are unable to obtain a medical card because they are unable to prove they are entitled to one. When they fail to take a child to a local doctor for care, social services are then called in.

"Social workers have contacted us with very serious child protection concerns. They have told us in some cases they have very little option but to take a child into care to give them access to services."

Although Ireland historically has been known for its traveller community, many Roma arrived only in recent years looking for a better life when countries such as Slovakia, Poland and the Czech Republic entered the EU.

Europe's total Roma population is thought to be as high as 10-12 million, with Turkey having an estimated population of 2.75 million and Romania with some 1.85 million.

Siobhan Curran warns against sensationalising the Roma issue.

"Any child protection case has to be taken seriously," she says.

"But we need to challenge the starting point that there's a connection between Roma and child trafficking."

- Published23 October 2013

- Published21 October 2013

- Published1 September 2012

- Published18 October 2012

- Published12 September 2012