Spying scandal: Will the 'five eyes' club open up?

- Published

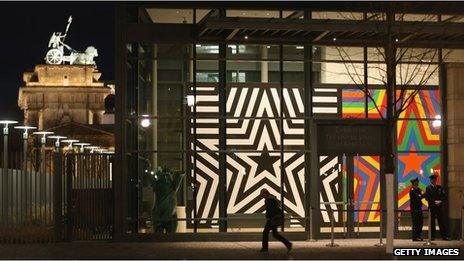

Germany has suggested it may seek a no-spy deal with the US, whose embassy is beside Brandenburg Gate

The 'five eyes' club was born out of Britain and America's tight-knit intelligence partnership in World War II and particularly the work at Bletchley Park, breaking both German and Japanese codes.

Code-breakers realised collaboration helped in overcoming some of the technical challenges and in being able to intercept communications around the world.

Out of this experience came what was first called BRUSA and then rechristened UKUSA - a top secret intelligence-sharing alliance signed in March 1946.

The details of the original agreement were classified for decades but were finally revealed in 2010 when files were released by both countries.

The arrangement is described as "without parallel in the Western intelligence world".

Soon after the beginning of the Cold War, GCHQ and the NSA were born and the alliance formed the basis of their extremely tight co-operation during the Cold War - the real heart of what has been known as "the special relationship".

The club was also expanded to include three other English-speaking countries - Canada, Australia and New Zealand and so became known as the "five eyes".

So how does this club work? It is based on sharing with each other and not spying on each other.

The US and UK human intelligence services (the CIA and MI6) do not run operations inside the other's country without permission, but while the CIA and MI6 do share information they are not nearly as closely intertwined as their counterparts GCHQ and NSA. They deal in what is known as signals intelligence, which deals with communications.

Under UKUSA, they share nearly - but not quite - everything, and do not target each other's nationals without permission.

The White House admits that the recent disclosures about US spying have caused diplomatic tension with America's allies

One document leaked by the fugitive Edward Snowden reveals that the protection extends when intelligence is shared with other countries outside the club (so called "third parties", a "second party" being any other member of the club).

An agreement between the NSA and Israel published by the Guardian newspaper read that Israel "recognises that the NSA has agreements with Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom that require it to protect information associated with UK persons, Australian persons, Canadian persons and New Zealand persons using procedures and safeguards similar to those applied for US persons".

In a way, Edward Snowden himself shows how close the alliance is.

An American, he had access to thousands of documents belonging to British intelligence. And so GCHQ has, in a strange way, become a victim of the club's intimacy and openness within its wall.

But given America's NSA is the largest partner by some way, it may be careful not to complain too much.

Just because a country is not in the club does not mean there is no co-operation with those inside.

Americans suggest the reason they collect so much data about call-records from countries in Europe is that they are looking for suspected terrorist plots and that they share what they find with national intelligence agencies so they can then follow them up (this is the same justification that the NSA has furthered for collecting some domestic call record data within the US).

"If the French citizens knew exactly what that was about, they would be applauding and popping champagne corks. It's a good thing. It keeps the French safe. It keeps the US safe. It keeps our European allies safe," Congressman Mike Rogers, the chairman of the US House Intelligence Committee, which oversees the NSA, told CNN at the weekend.

GCHQ and NSA share intelligence about communications, using hi-tech versions of Alan Turing's WWII Bombe decryption machine (above)

But of course, while this might explain some of the spying, it does not explain eavesdropping on Angela Merkel's phone or bugging EU offices.

That looks like traditional state-on-state espionage and is what is likely to be most angering European officials (although for public consumption they still need to make angry noises and protests about the collection of their ordinary citizens' call records).

Germany and France have suggested they may seek deals to end this kind of state-on-state espionage activity and one of the interesting questions is the extent to which what they really want is a no-spy deal like the one Britain enjoys, and effective membership of the existing club (or some modified version of it).

However, one general rule about intelligence is that the more a secret is shared, the less secret it becomes.

It is one reason why some are sceptical of sharing too much intelligence with the whole EU - secrets may not stay secret among 28.

Could something be possible with some of the countries though?

Some senior British intelligence officials are understood to be supportive of deepening and broadening the partnership with some European allies, although whether this means going so far as letting then into full membership is another matter.

But with embarrassing revelations likely to continue, the way the club currently operates may well have to change.