Nazi art trove raises host of legal questions

- Published

Works by Otto Dix and Marc Chagall are among the 1,406 pieces found

It is a treasure trove of artistic delight - but also now a Pandora's box of legal questions. The discovery of an art collection to excite any gallery curator has also opened a host of legal controversies.

Art connoisseurs relish the thought of a Chagall which was previously unknown, or of masterworks by Picasso, Renoir, Matisse, Canaletto, Max Beckmann, Albrecht Duerer and others once thought destroyed.

But the descendants of those robbed by the Nazis - and their lawyers - may question ownership.

Questions abound. Who owns the work now? What crime may have been committed (apart from the obvious and monstrous one of the original theft of the paintings from their original rightful owners)? Where will the works now go?

Law at the time

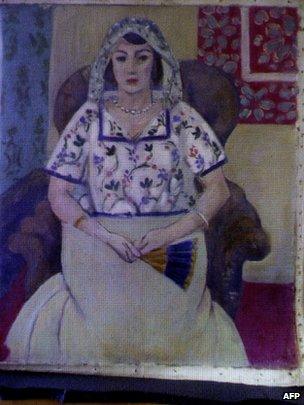

This painting has been attributed to Henri Matisse

The matter is complicated because Hildebrand Gurlitt, the German art dealer who acquired the paintings in the 1930s and 1940s, may well have come by them within the law at the time.

He was not the one who looted Jewish homes but simply the dealer to whom the Nazis gave the works to try to sell, or who bought some of the works himself. In fact, he was part Jewish himself.

That means that the son Cornelius Gurlitt, who kept the 1,406 works to himself in his apartment in a quiet and well-heeled part of Munich, may not have been breaking the law. He and his mother simply kept the work owned by his father when the dealer died.

Remember, the discovery of the art came because of an investigation about tax and customs duty.

The investigator in the press conference said that he and the authorities had questioned the son and were not planning more questions.

They did not know where he was, though they did indicate that they knew how to contact him. This indicates that they do not suspect him of any major crime.

Grey area

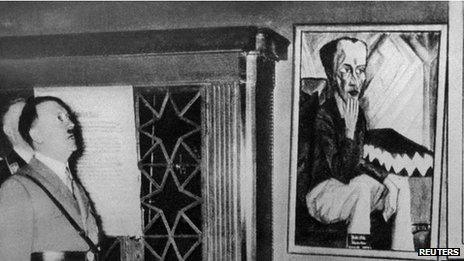

The collection itself divides into two categories. There are those paintings described by the Nazis as "degenerate" because they were painted by Jews or because they had content the Nazis didn't like - too decadent and "modern".

And there are older works looted by the Nazis when they occupied countries, particularly France. This part includes works by Renoir, for example, and other French masters.

The works taken from the walls of German galleries in 1938 because the Nazis felt they were inappropriate were done so within the laws of the time, so lawyers say that it will be very difficult for anyone to argue that they now have entitlement.

Adolf Hitler is seen inspecting paintings despised by the Nazis, in 1935

But any works simply looted from Jewish homes may be easier for the descendants to recover.

There is, though, a grey area over works sold by Jews who were fleeing for their lives, if the fugitives sold those works at prices way below their normal market value.

If the dealer bought them legally but at a knock-down price, their legal status would be a matter of much dispute.

Lost and found

On top of that, there is a controversial 30-year limit in Germany on claims by the descendants of those robbed of their paintings. And, obviously, 30 years from 1945 means that the latest claims were eligible only until 1975.

If you think a painting stolen from your ancestors may be in the trove, it will not be easy to find out. The investigators have decided not to put the works online. It would be for you to contact them with your query.

Some things, though, are clear. More than 1,000 works of art once thought lost are now found. And also some works of art which nobody even knew existed now do exist.

But this tranche of newly found paintings is only a fraction of those looted by the Nazis and later scattered among various collections or lost.

How many of them lie in some drawer in a darkened room in a lonely recluse's home, waiting to see the light of day?

- Published5 November 2013

- Published5 November 2013

- Published4 November 2013

- Published4 November 2013