Bulgarian protests: Students determined to overthrow system

- Published

The student protesters are operating out of a lecture theatre

For months on end, furious Bulgarian protestors have been gathering in front of parliament in Sofia to accuse the government of corruption and demand its resignation.

The latest unrest began when Bulgaria's new government tried to appoint controversial media mogul Deylan Peevski to head the national security agency in June.

Mr Peevski's appointment was quickly reversed but the protestors are refusing to abandon their crusade to clean up Bulgarian politics.

Outside the chained gates of Sofia University, a young man is being berated by a group of angry senior citizens. An elderly lady wearing a green crocheted hat slaps at him with a matching shopping bag and is shouting so furiously that droplets of her spittle are flying into his face.

I assume she and the other pensioners are sick of the five months of protests in the city and am astounded when I understand that they are yelling at the young man because he wants the occupation of his university to end and his lessons to resume.

"Do you know how many demonstrations I've been on to help your generation?" screams the woman. "Fight on and don't be such a damn coward!"

An old man pushes the student's shoulder roughly.

"You want to go back along the road to Moscow?" he shouts. "Or do you want to help pull Bulgaria on the path towards progress?"

Embarrassment

The last government was brought down amid protests over a hotchpotch of causes including soaring energy bills and low pensions, but this time the people are protesting about corruption in the political elite, shady ties between the government and businesses and power-grabbing oligarchs.

Leta, Dimitar and Alexander are members of the Moral Revolution movement

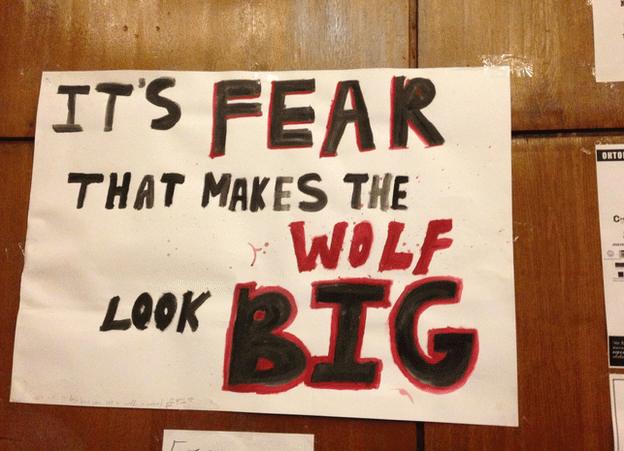

Protest posters dot Sofia University

Students have led the protests near parliament

Since late October, the students have energised the fight with a sit-in at the university. About 500 of them now squat in the lecture halls, demanding the government resigns. They are calling their movement the Moral Revolution.

It is cold in the dark university building and it smells rather fetid but Leta, Alexander and Dimitar kick away the piles of sleeping bags and half-eaten food on the floor and benches and invite me to sit down.

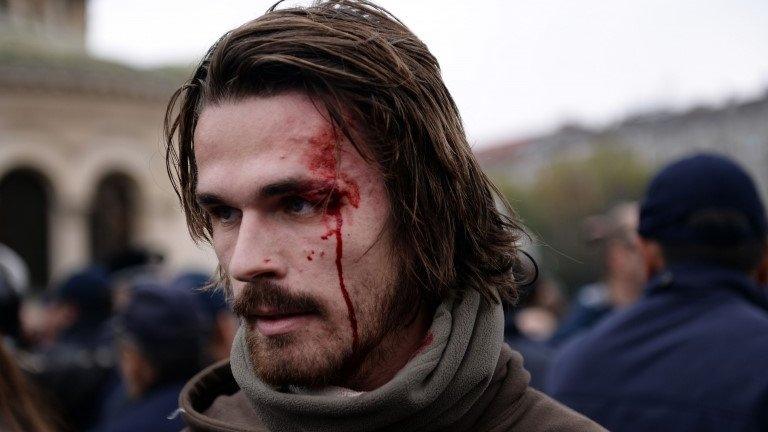

Alexander is sporting a swollen and cut eye after falling in a scuffle with riot police but his enthusiasm for the protests has not been dampened.

"There is corruption at every level in Bulgaria," he tells me. "And you know we, the young people, have to carry on the fight for those who are too old now to march. Because they marched for us. We have to give them hope things can change."

Pony-tailed Dimitar tells me he is a seasoned protestor. He has only missed five nights of demonstrations since the protests began in June. On the blackboard in front of him someone has chalked the single word "Ostavka!" - "Resign!".

"We've never got rid of that communist mentality that you have to pay to get what you want," he explains.

"People here sort of accepted corruption as a part of life but now we want the Bulgarian people and the political class to wake up!"

Leta is buoyed up on nervous energy but the dark circles under her eyes tell me she has not slept properly for some time.

She and Alexander discuss how embarrassing it is that wealthier EU countries like Britain regard Bulgaria simplistically as a poverty-stricken haven of corruption.

"It annoys me," she says.

"But that is the image we give. You know so many people are leaving Bulgaria to go to richer EU countries but our main slogan is that we that we want to stay here and build Bulgaria into a country that we can be proud of one day."

'Nothing new'

From outside the lecture hall, a raucous cheer and piercing whistle rallies the first of the day's marches. More than three-quarters of Bulgarian people support the general protests. With their drums and loudspeakers, they are delivering the same, albeit more audible, message that Brussels has been giving the political elite for the past seven years.

"Yes," agrees Justice Minister Zineida Zlatanova as she sips a breakfast fruit smoothie in her office.

"The issue is not new and we've been under special monitoring by the EU for seven years."

She admits that the protests are "alarming" and that not enough progress has been made in reaching greater transparency but she points out that the protests are aimed not just at the ruling Socialist-led coalition but at the political elite as a whole.

"And changing a government with street protests is not a part of democracy," she concludes firmly.

The government will not back down but it has suggested some populist measures to try to shore up support. Reversing the smoking ban in public places is among the measures proposed. Others, such as extending the moratorium on foreigners buying land in Bulgaria, actually break the terms of its EU accession treaty.

As darkness falls, the students troop off to join the office workers who are already spilling out of their offices on to the streets in front of parliament. A raucous hissing and booing begins as an MP is spotted trying to leave his office. Some of the protesters wave brooms, demanding a clean sweep of the political class.

Despite promises to kick-start the economy and to create more jobs, it seems doubtful that the ruling coalition will last a four-year term and analysts predict early elections next spring. But with every political party now held in equal contempt by the electorate, who will be able to govern Bulgaria?

- Published20 November 2013

- Published12 November 2013

- Published23 July 2013

- Published20 January