Khodorkovsky release: What fate awaits freed dissident?

- Published

It was an extraordinary turnaround. Only a couple of years ago President Vladimir Putin ruled out the idea of releasing his archrival Mikhail Khodorkovsky early, noting that a "thief should sit in jail", and hinting he may well have had blood on his hands.

Now the Russian President has declared "10 years is long enough" and granted him clemency on humanitarian grounds.

So what does this change of policy mean?

Mr Khodorkovsky has not said much yet. But in a statement on his release, he did admit that it was he, the prisoner, who asked for a pardon on family grounds.

Though this did not, he stressed, amount to an admission of guilt and an acceptance that his prison sentence was justified.

This statement does represent a shift.

Up until recently, Mr Khodorkovsky was reportedly refusing to accept exile as a condition for release, or even request a pardon, arguing this would imply he was accepting the Russian sentences handed down to him - whereas he claims that, for 10 years, he was the victim of a miscarriage of justice.

A decision to compromise now and accept a Kremlin deal would be completely understandable. Some reports have suggested Mr Khodorkovsky was being threatened with the prospect of a third trial.

This could have meant incarceration for yet another decade in some remote and snowy penal colony. He may have felt his time in prison had served its purpose.

What we do not know is whether he was forced to accept conditions for his release - to remain in exile and agree not to return to Russia, for instance?

Forced silence or exile?

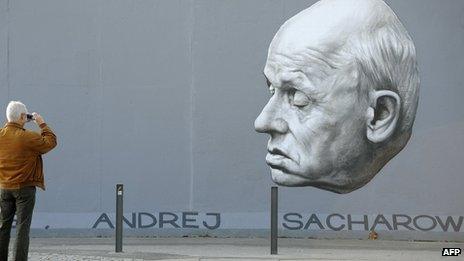

In other words, given that Mr Khodorkovsky's dignified endurance of 10 years in jail has transformed him from powerful oligarch to respected latter-day dissident, who should we be reminded of on his release - Andrei Sakharov or Alexander Solzhenitysn?

Physicist Andrei Sakharov became a figurehead for the democratic opposition

The Soviet dissident and physicist Andrei Sakharov was released from internal exile by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev at the end of 1986 as part of perestroika reforms.

It turned out to be an important signal of political liberalisation after over 70 years of Soviet Communism. Sakharov went on to become a figurehead for the new democratic opposition, which challenged Communist rule, a powerful voice of moral authority.

Will Mr Khodorkovsky be allowed to join and lead the political opposition to Mr Putin? It seems unlikely.

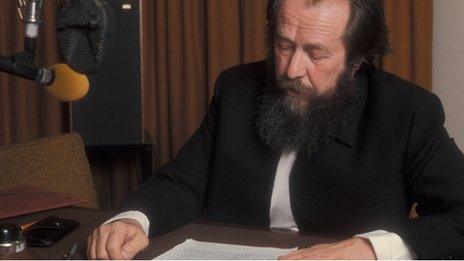

So look instead to the fate of the towering figure of Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the Nobel Prize-winning dissident writer and former political prisoner who won liberty in a different way.

In 1974 he was arrested and deported out of Russia, and deposited in the United States where he spent years in reclusive exile in Vermont.

Dissident Nobel Prize winner Alexander Solzhenitsyn was sent into US exile

The Soviet KGB chief Yury Andropov rightly calculated that one way to rid the Soviet Communist authorities of this troublesome critic was to force him into emigration, where he no longer attracted the same attention.

If that is Mr Putin's calculation, it may not be so simple.

Unlike Solzhenitysn, Mikhail Khodorkovsky speaks fluent English and, in our era of global internet connections, his voice and comments can still reverberate back into Russia in a matter of milliseconds - unless of course he has agreed not to become a thorn in President Putin's side again, but to limit his activities to non-political interests.

All that is for the future - details of his release have yet to be revealed and scenarios yet to be tested.

Olympic aspirations?

Perhaps President Putin's more immediate motivation in freeing his former archrival is more tactical - aimed at next year's Russian Olympics.

Already a broader amnesty has been agreed for other high-profile prisoners - the two young female singers from the Pussy Riot rock band and the foreign Greenpeace activists currently awaiting trial in Russia.

Liberate them and Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and, even if gay activists still try to infiltrate their placards into the Olympic Village, there is maybe less chance of a broader human rights protest to spoil the spectacle of the Russian Olympics in Sochi, a sporting event which Mr Putin has personally tied his reputation to.

Freeing Mikhail Khodorkovsky also removes a man who had become a symbol of the flawed nature of Russia's criminal justice system.

Russia may be trying to appease human rights protesters ahead of the Olympics

As soon as reports of his pardon emerged, the stock market in Moscow went up, in anticipation that perhaps foreign investors would take heart at the news.

Mr Putin too is aware that Russia desperately needs more foreign investment to help upgrade crumbling infrastructure projects and to diversify its flagging economy.

And maybe more generally, Mr Putin has concluded that Mr Khodorkovsky no longer represents a viable political threat to him.

His assessment may be that whatever influence he wields among Western liberals and disaffected Russians, Russia is now a place where conservative values (with a small "c") flourish.

For many ordinary folk - the ones Mr Putin now looks to in order to secure his power base - Mr Khodorkovsky remains a hated former oligarch, a man who they believe built his wealth on ill-gotten gains stolen from the Russian state and the Russian people.

- Published22 December 2013

- Published20 December 2013

- Published22 December 2013