Turkey's Erdogan and year of 'foreign plot'

- Published

Mr Erdogan faces local and presidential elections next year

"Since 2003, we've been trying to get Turkey into the top 10 countries in the world," declared Turkey's Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan on 18 December.

"But some people are trying to stop Turkey's fast growth and development. Some of these people are abroad."

For Mr Erdogan, 2013 was the year of the foreign plot.

He saw it first in May and June during a wave of street protests, and he saw it once more at the end of the year, when prosecutors detained a number of his allies on suspicion of corruption.

The prime minister was unwilling to consider the alternative - that some of his fellow citizens might have real grievances against the way he governed.

Mr Erdogan's opponents accuse him of losing touch with ordinary people, and even suggest that he is suffering from so-called hubris syndrome - a condition that affects leaders who have spent more than a decade in power.

The first wave of opponents rose up in May against the government's plans to convert Gezi Park in Istanbul into a replica military barracks.

The police used tear gas to drive protesters from Gezi Park

The environmental demonstration soon became a mass protest against the prime minister's perceived authoritarian manner, and against the way in which the government was seeking to transform Istanbul without proper consultation.

The prime minister was unmoved - he called the demonstrators "capulcu"(riff-raff) - and ordered the police to retake the park.

Gezi Park is now open again, but its fate is unclear. Istanbul's courts are currently examining the government's redevelopment plans.

Dawn raids

During the summer, at nine o'clock every night, residents of neighbourhoods which opposed Mr Erdogan would clang their pots and pans to show their defiance.

They wanted him to step down, but he saw no reason to do so.

Now the nights are quiet.

The protesters failed to turn their anger into a lasting, organised political movement of their own capable of challenging the government at the ballot box.

Head of Istanbul's police Huseyin Capkin (R) was dismissed over the dawn raids

But, months later, some of the same grievances that provoked the original protesters re-emerged.

This time the challenge was potentially much more serious.

On 17 December, prosecutors and police officers organised dawn raids against more than 50 businessmen, including the sons of three cabinet ministers - all allies of the prime minister.

The prosecutors accused the businessmen of corruption.

In particular, they suspected that some of the detainees gave or received bribes to let controversial building projects in Istanbul go ahead.

Unhappiness with the physical transformation of Turkey's largest city was the issue that linked May's occupation of Gezi Park and December's dawn raids.

'No Gulenometer'

Mr Erdogan stated his belief that the occupation and the raids were each orchestrated from abroad.

In May and June, he or his advisers blamed a variety of forces for the occupation of Gezi Park: an international interest rate lobby; the foreign media; one adviser even suggested that the airline Lufthansa was in favour of the protests.

In December, Mr Erdogan reacted to the dawn raids by blaming a movement "with branches in Turkey. I will not discuss their identity. You all know who they are".

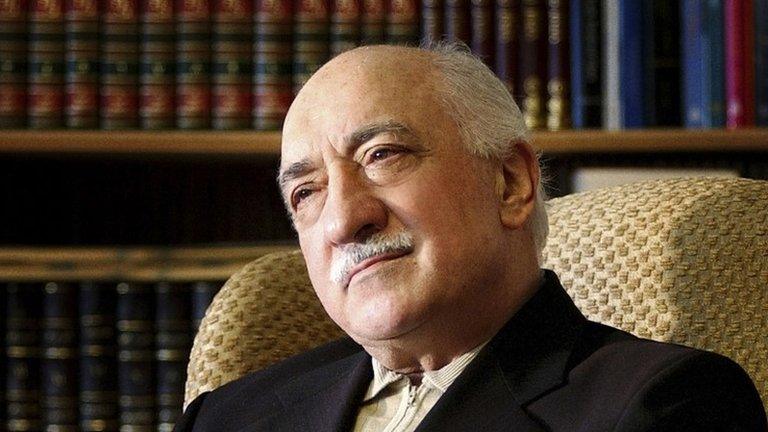

He did not need to give a name. Everyone knew who he was talking about: the Gulen movement - named after its leader, a 72-year-old Islamic scholar, Fethullah Gulen.

From his base in Pennsylvania, US, Mr Gulen runs an Islamic social and cultural organisation with more than 1,000 schools in the Islamic world - including many in Turkey.

His followers praise Mr Gulen for preaching a moderate form of Islam and suggest that he should win the Nobel Peace Prize.

For years, Mr Gulen's loyalists (known here as Gulenists) broadly lined up with Mr Erdogan. They shared the prime minister's belief of a greater role for Islam in Turkey's secular state. The movement helped Mr Erdogan to win three general elections.

Crucially, an undeclared Gulenist network in the judiciary and the police helped the government to remove the military from politics.

"There is no Gulenometer to measure the sympathy or support of the people for Gulen's ideas," says Bulent Kenes, the editor-in-chief of Today's Zaman, a newspaper sympathetic to the Gulen movement.

"In Turkey everyone knows that people who have sympathy with the ideas of Mr Gulen are everywhere - in media, in the business sector, in the police department, in the government, in parliament, in the military, in the judiciary."

Organised opponent

This summer, long-standing differences between the Gulenists and the prime minister re-emerged.

The Gulen movement was unhappy with the way Mr Erdogan dealt with the Gezi Park protesters.

It was angered in November when the government suggested closing down a number of private schools, including those run by Hizmet, the Gulen movement.

Many here believe that the same Gulenist network that once went after the military has now gone after the prime minister's allies - a charge that the movement itself denies.

"This is the clash of the egos," said one young woman at a recent anti-corruption demonstration in Istanbul's Besiktas neighbourhood.

"Gulen is behind the curtain. Erdogan is in front. This is the real fight between two powers, two egos."

The prime minister has responded to the detention of his allies by dismissing senior police chiefs. The power struggle between Mr Erdogan and his new Gulenist opponents has shaken the country.

"In the end, neither side will win," says Ahmet Sik, who was jailed for writing a book on the Gulen movement's power within the judiciary.

"This is only the beginning. Both sides will lose credibility. They'll get weaker."

In 2014, each side faces judgement.

In March, local elections will be held. Then, in the summer, the country will vote for a new president.

Over the last year, Mr Erdogan has positioned himself as a potential candidate - hoping perhaps to take many of the executive powers of the prime minister's office with him to the presidency.

But he now faces an organised opponent within the system he has dominated for a decade.

Mr Erdogan's political skills will be tested - foreign plot or otherwise.

- Published23 December 2013

- Published18 December 2013

- Published18 December 2013

- Published22 August 2023