Q&A: Turkey's power struggle

- Published

Turkey's Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is facing the biggest threat to his authority since his election 11 years ago, involving a corruption investigation and a murky power struggle.

What is the crisis about?

Mr Erdogan is the most dominant Turkish leader in decades, but is facing an unprecedented challenge, on various fronts. The most immediate threat comes from a police investigation into alleged corruption among senior members of Mr Erdogan's Islamist-rooted AK Party.

Analysts believe that the investigation stems from a rivalry between the AKP and the followers of influential Muslim preacher Fethullah Gulen, who hold senior positions in the police and judiciary. Mr Erdogan has condemned what he calls a "dirty plot" against his government.

The crisis follows large anti-Erdogan protests last year, and threatens to undermine the prime minister's undeclared ambition to be elected president this summer.

What corruption?

In December 2013 police arrested dozens of people in raids, including the sons of three cabinet ministers, and senior figures in banking and construction. The allegations included bribery to win public tenders and smuggling gold to Iran.

Four ministers resigned. One, Environment Minister Erdogan Bayraktar, urged Mr Erdogan to step down himself, saying he knew about the construction projects. Mr Bayraktar's son was later released, but the other two sons were charged.

How has Mr Erdogan responded?

He says the probe is a conspiracy against his government, allegedly involving foreign enemies, external.

The day after the arrests, five senior police chiefs were removed from their posts. Other culls followed, with 350 officers reassigned in January.

Mr Erdogan also struck a blow against the judiciary. In a significant U-turn, he suggested he would support retrials for some of the hundreds of military officers, academics and journalists convicted of involvement in military plots to overthrow his government. Many of the prosecutors in these coup trials - known as Ergenekon and Sledgehammer - are the same ones pursuing the corruption case.

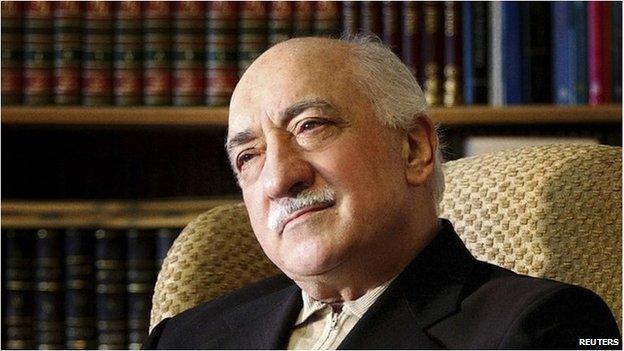

Where does Fethullah Gulen fit in?

Both the police and prosecutors in these cases are suspected of being Gulenists - followers of the moderate Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen. He has lived in the US in self-imposed exile after charges were brought against him for trying to undermine Turkey's secular state.

It is thought shis worldwide Hizmet movement may have millions of followers, running schools, think tanks and media outlets, and could be worth billions of dollars. It is also believed to have infiltrated Mr Erdogan's AK Party.

The movement has until now helped drive the three election victories of the AKP. Part of their informal collaboration involved Gulenist prosecutors pursuing army officers, as part of the AKP campaign to weaken the all-powerful military's hold over politics.

But after that achievement the two sides seemed to grow suspicious of each other's power. The government announced that Gulen schools offering supplementary education would be shut down. Analysts saw the corruption probe as retaliation.

And the army?

An ally of the prime minister suggested the corruption scandal might be a plot to trigger a military coup. The army pushed out four civilian governments between 1960 and 1997, but said it had no intention of getting "involved in political debates" this time.

The military has traditionally seen itself as the guardian of modern Turkey's secular values. But it has been significantly weakened by reforms and the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer probes - which to many critics became a vehicle to round up and jail government opponents.

No-one suggests the military is about to recover its former power, says the BBC's James Reynolds, but if convicted officers are to be retried, the army could be a beneficiary of the AKP-Gulenist power struggle.

What is the political impact?

The past year has been the most difficult yet for Mr Erdogan. In mid-2013 protests centred on Istanbul's Gezi Park accused the prime minister of increased authoritarianism, and of seeking to impose conservative Islamic values on Turkey. When he took a hard line against the protests, and police waded in, he faced criticism from international allies previously impressed by his democratic credentials and business acumen.

The latest scandals may undermine support for the AKP ahead of local elections in March. And upset Mr Erdogan's hopes of becoming Turkey's first directly elected president later this year.

What is the effect internationally?

The exposure of corruption and the way organs of state seem to be the playthings of the powerful in Turkey has damaged the country's image and faith in the rule of law.

It has provided ammunition for Turkey's critics and embarrassed those who see Turkey as a successful Muslim democracy with a future in the European Union.

The Turkish lira has fallen to a record low, threatening the foreign investment which has underpinned the economy's recent growth.