Whatever happened to the eurozone crisis?

- Published

- comments

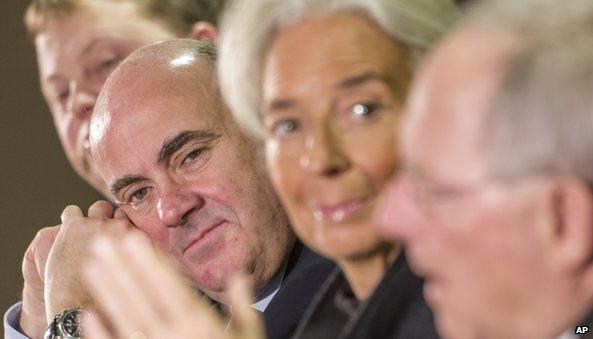

The IMF wants the eurozone to get its banking union in place soon to help revive growth

To many people the eurozone crisis has disappeared. It is off the front pages. It has certainly left the TV screens. I have heard prime ministers and presidents declare the crisis "over".

The Anglo-Saxon jeremiads have been proved wrong. There have been no exits from the single currency and significant steps have been taken to fix the design flaws.

Casting around it is not difficult to find "green shoots". Only on Tuesday, Spain, with its chronic unemployment, upgraded its growth forecast for 2014 to nearly 1%.

The Republic of Ireland, having almost been bankrupted by its banks, has felt strong enough to leave the safety of the bailout programme. Portugal may soon follow.

Mixed signals

Greece, which has seen its economy decline by 25% in five years, is now running a primary budget surplus, excluding interest payments.

Greece is months behind in negotiations with its creditors and a third bailout is likely

We learnt on Tuesday that the surplus might just reach 1bn euros (£819m; $1.4bn).

Borrowing costs for the most vulnerable countries have fallen to levels not seen since 2010.

Italy's two-year borrowing costs have fallen to their lowest level since the launch of the euro. Tremors in the emerging markets have scarcely ruffled Europe - so far.

And so optimists have emerged among us - those who follow the statistical twists and turns of the single currency. They have seen the glass and judged it to be half-full.

It needs to be said at the outset that Europe is still enjoying the "Draghi effect": the reassurance given by the President of the European Central Bank (ECB) that he would do "whatever it takes" to defend the euro - and no-one seems willing to bet against the ECB.

And yet it is a curious kind of recovery, full of faults and fissures.

Take Spain. Early in the crisis it enthusiastically embraced structural reforms, making it easier to hire and fire workers.

Productivity has improved strongly. Its labour costs have fallen and its exports have surged.

And yet! House prices are still falling. Bad loans are still rising, as is public debt. There are signs that unemployment is beginning to fall, but even if Spain achieves growth of 1% it will have little impact on the 5.9 million people out of work.

Future growth will have to depend on exports and investment but not on domestic demand.

Patience running out

Take France. Its Finance Minister Pierre Moscovici boldly declared recently , externalthat "France is modernising and reforming".

He took a swipe at his country's critics and insisted France "deserves the world's trust".

After much badgering from its neighbour across the Rhine, President Hollande has pledged to cut spending by 50bn euros (£41bn; $68.3bn) by 2017, on top of the 15bn-euro cuts already announced for 2014.

His reforms will take time and in France patience is running out. This week France saw the numbers out of work rise above 3.3 million people. The promise that unemployment would fall by the end of 2013 lies unfulfilled.

Take Italy. It is spluttering its way out of recession. Its economy has not really grown since the middle of 2011. It has now embarked on a privatisation drive which is expected to raise 12bn euros over the next two years.

These sales are driven by the need to reduce Italy's public debt. It is forecast to reach 133% of GDP this year. It is a reminder that this was once defined as a sovereign debt crisis, yet in country after country debt is higher today than it was in 2009.

Germany is motoring, but many of its eurozone partners are still struggling

Prosperity or stagnation?

And then there is Greece. Yes it has eked out a primary budget surplus, but Greece is not in rude financial health, external. There is a funding gap this year of probably 4bn euros. Some note that it is beginning to miss its fiscal and structural targets.

Negotiations with its creditors are months behind schedule. A third bailout is likely. Some believe - like the IMF - that growth will only emerge if a major chunk of its debt is written off. Greece is unfinished business.

And for some of these countries falling inflation makes it more difficult to meet public debt targets. That puts pressure on weaker economies to cut costs further, just to compete with countries like Germany.

To politicians and officials the key question hanging over the euro was its survival. For the moment that question has been laid to rest.

But to the public there is perhaps a more important question - does the single currency deliver prosperity or stagnation?

On Tuesday EU Economics Commissioner Olli Rehn declared that "consumer confidence has reached its highest level since January 2008".

He foresees continuing recovery. And yet doubts persist that this is a flawed recovery.

It was perhaps best summed up last week by Total's chief executive Christophe de Margerie, who opined that "the continent needs to start from scratch in terms of economic policy to overcome the evils of high unemployment and stagnant growth".

- Published25 January 2014

- Published25 January 2014

- Published23 January 2014

- Published15 January 2014