Why stakes are high in European election

- Published

European Parliament elections explained

This year's elections to the European Parliament - taking place on 22-25 May across the EU - will see an unprecedented battle over the bloc's powers and role.

For the first time anti-EU parties will pose a major challenge in many countries.

The vote will be the biggest yet - the 751 MEPs elected will represent more than 500 million citizens in 28 member states.

Do these elections matter?

Six MEPs give the BBC their views ahead of European elections in May

The European Parliament is the only directly elected institution in the EU, and therefore this is the only chance - once every five years - for voters to decide who will represent them in Brussels.

Members of the parliament (MEPs) are only one branch of power in Brussels - but since every new law must get their approval, they have an essential role.

The stakes are particularly high this year because the economic crisis has sharpened the debate about the EU's future. Do voters want closer integration, even a federal Europe, or do they want powers to be repatriated to their national parliament? Or do they want their country to leave the EU?

If many people vote for the latter, a big anti-EU bloc could significantly disrupt the parliament.

What are the big issues?

Migration across EU borders has become more controversial

Migration could be high on the agenda for many voters. Freedom of movement in the EU has been challenged by many politicians, not only in the UK, because EU enlargement has hugely increased the flow of migrant workers.

Many voters are worried about jobs. With millions of young Europeans struggling to get into employment, jobs creation and growth will be big campaign themes.

The EU's battle with the debt crisis has fuelled antagonism in many countries towards the EU, opinion polls suggest. So Eurosceptic parties such as the National Front (FN) in France and UK Independence Party (UKIP) are expected to do well.

.gif)

Does it affect the top jobs?

Potential successors will soon compete to replace EU Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso

Yes. For the first time the result will affect who gets appointed president of the European Commission, the EU executive branch that shapes laws and enforces compliance with EU treaties.

The candidate will be chosen by the 28 government leaders (the European Council) taking account of the election result, but then must be approved by MEPs. If there is no such majority a new candidate must be put forward.

MEPs will also vet each candidate for the 27 EU commissioner posts - some have been rejected in the past.

Can race for top job pull in voters?

What are the parliament's powers?

How the European Parliament works

Since the last election, MEPs' powers have expanded considerably, under the Lisbon Treaty. They now negotiate legislation with national government ministers - the Council - in what is called "co-decision", then parliament votes on the laws.

MEPs now have an important say in big budget areas, such as agriculture and regional aid.

They can press the Commission to legislate on particular issues. They can also act on issues raised by voters who petition them directly. That was notably the case in the EU fisheries reform, where public pressure made a big impact.

MEPs' consent is also required for EU trade agreements with non-EU countries, and for admitting new states to the EU club.

How do they get elected?

Voters in Slovenia: Eight East European countries joined the EU in 2004, and three more later

By proportional representation (PR). This is seen as especially advantageous for smaller parties, compared with first-past-the-post, the system used in UK national elections. That is why UKIP, for example, can win seats more easily in the European elections.

Under PR, each member state can operate either an open or closed-list system. With the open list, voters can state a preference for one or more candidates. That system operates in 16 countries, including Austria, Belgium, Italy, Poland and Sweden.

Under the closed list, voters choose a party, and the parties themselves decide the pecking order for their candidates. Eight countries use that system, including France, Germany and the UK (except Northern Ireland).

Most parties campaign on national, rather than pan-European, themes, since people have been shown to vote on local issues. However, the Greens have a single, pan-European manifesto.

How are groups formed?

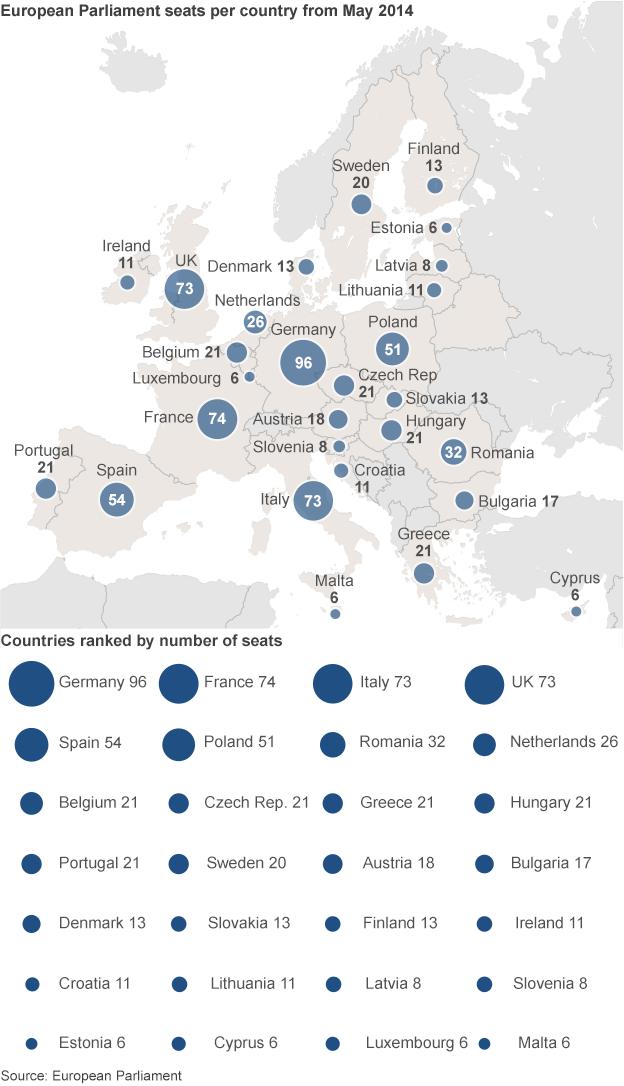

The number of seats per country is decided by its population. Germany will have the most - 96; France 74; Italy and the UK 73 each. Cyprus, Estonia, Luxembourg and Malta get six each.

Once elected, most national parties join like-minded transnational blocs in the parliament. So a UK Labour MEP will sit with the Socialists and Democrats (S&D), while a German Christian Democrat sits with the European People's Party (EPP).

Groups must have at least 25 MEPs, from at least seven countries. Being in such a group means an MEP can have more influence on legislation and the party gets vital funding from the parliament.

The groups span the political spectrum, from far right to far left, but the biggest blocs are centre-right, centre-left and liberal. No group has ever had a clear majority, so compromise and deal-making are the name of the game.