Q&A: EU freedom of movement

- Published

Freedom of movement is a fundamental right in the EU. But the UK and some other countries are concerned about the existing rules.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron is proposing limits to EU migration. But that is highly controversial, and Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel has warned against meddling with freedom of movement in the EU.

What does the EU say about freedom of movement?

An influx of Poles to Cheshire, UK, prompted this road sign in Polish warning of a diversion

It is a core principle, enshrined in the EU treaties, which works in parallel with the other three basic freedoms in the single market: freedom of goods, capital and services.

The European Commission says it is the right most closely associated with EU citizenship. An EU survey suggests, external it is seen as the EU's most positive achievement, ahead of peace in Europe, the euro and student exchanges.

More than 14 million EU citizens are resident in another member state - 2.8% of the total EU population.

Before the EU's big eastward expansion in 2004, citizens of the former communist bloc countries had less freedom to travel than Western Europeans. That was a legacy of the Cold War.

The EU's outgoing Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding told students in Belgium last year: "Today, as European citizens... you can travel 3,000km (1,860 miles) across Europe - from Vilnius in Lithuania to Valencia in Spain - without once stopping at a border."

And outgoing Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso warned the UK that its EU partners would not accept any "arbitrary cap" on migrants.

Freedom of movement helps to fill job vacancies in many EU countries and gives employers a wider talent pool, the Commission argues. Germany, resilient in the euro crisis, is proving a magnet for jobseekers from recession-hit countries like Spain, Italy and Greece.

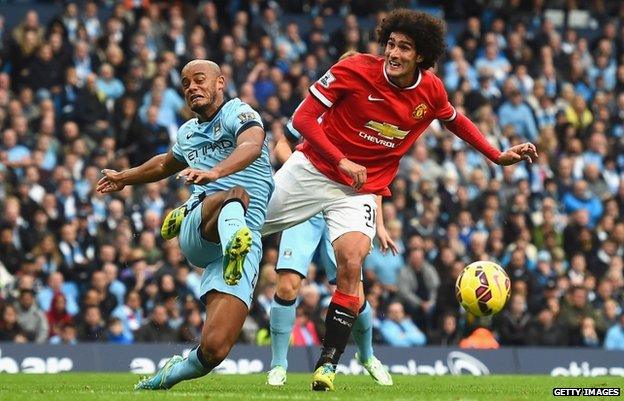

Europe's football clubs are among those who have benefited from the freedom of professionals to move.

What is the UK position?

Freedom of movement: Belgian players and Manchester rivals Vincent Kompany (L) and Marouane Fellaini

The UK government champions the single market and wants barriers to trade in the services sector removed, as services account for about 75% of total EU gross domestic product (GDP) and most of the jobs in Europe.

Free movement of labour is fundamental to a functioning single market, and is seen as one of the great strengths of the US economy.

But UK Home Secretary Theresa May says free movement of workers must not lead to mass migration, and she wants changes to the rules at EU level.

The UK wants the power to cap the numbers of EU migrants. One way would be to require new member states to reach a certain level of income or economic output per head before their citizens can have full rights to free movement.

Opinion polls and the rise of the UK Independence Party (UKIP) suggest that worries about immigration have fuelled widespread British scepticism or hostility towards the EU.

Freedom of movement was a big part of the British debate in the May 2014 European elections. UKIP, hostile to the EU, came first, winning 24 seats. Previously it had 13 MEPs in the European Parliament.

Eurosceptic parties across Europe boosted their representation, so now they occupy about one-third of the total seats.

Europe's budget austerity has made the immigration issue more acute, especially as youth unemployment is widespread.

Most EU countries imposed temporary labour market restrictions on workers from the eight East European states which joined in 2004, but the UK, Republic of Ireland and Sweden did not. The UK saw an unexpected surge in migrants from those states - the majority from Poland.

Net migration from those states to the UK reached nearly 400,000 in 2004-2011, and a UK census in 2011 suggested about 1.1 million residents were born in those countries.

The concentration of migrants in certain areas has put extra pressure on services such as schools and hospitals.

Why was there concern about Bulgaria and Romania?

EU expansion in 2004 saw thousands of Polish jobseekers boarding buses to the UK

They are the EU's poorest member states - they joined in 2007. They remain under special monitoring by the EU because of long-standing problems with corruption, abuses in their justice systems and organised crime.

The UK and its EU partners did not fully open their labour markets to Bulgarians and Romanians when the two countries joined, but those temporary restrictions disappeared in January 2014.

Thousands of Bulgarians and Romanians had already found work in other EU countries, under various work permit schemes. They are employed seasonally, for example, on UK farms.

There is a big gap in average wages, external - and that is a big driver of east-to-west migration. In 2012 company employees in Bulgaria got on average €3,598 (£2,809; $4,495) net annually, and in Romania €4,004. For the UK the figure was 33,216, for Germany 26,925 and Denmark 32,396.

For years the Netherlands has vetoed the bids of Bulgaria and Romania to join the EU's Schengen passport-free zone, external. Most EU countries - but not the UK, Ireland and Cyprus - are in Schengen, where border checks are non-existent or minimal. The Netherlands says it needs to see positive EU monitoring reports on the two Balkan nations before it will lift its veto.

The Schengen issue is also important because Bulgaria borders on Greece and Turkey, which have become major transit countries for migrants trying to enter the EU from Asia and Africa, often illegally.

Isn't the real problem EU migrants claiming benefits?

Serbia is a transit country for many EU-bound illegal migrants and takes their fingerprints at the border

The UK government has warned of "benefit tourism", saying it is unacceptable for jobless migrants to "shop around" in the EU for social welfare. That is why the UK is insisting on tighter controls, so that only genuine workers and their families, legally resident, are eligible for benefits.

Officials in the Netherlands and Germany have voiced similar concerns.

In recent years France has carried out mass deportations of marginalised Roma, sending them back to Bulgaria and Romania, after they had established squalid camps on the edges of French cities.

The EU has a three-month rule for migrants from EU countries - after three months it is the national authorities' duty to screen them with a "habitual residence test". That involves checking on their activity, including their source of income if they are students; their family status; whether they have a job offer and their housing situation.

In most EU states migrants from other EU countries are net contributors to the cost of welfare and public services. the European Commission says. Most are working and paying taxes. They form less than 5% of total recipients of non-contributory benefits - that is, state benefits which are not funded by individual or employer contributions.

According to EU data, , external78% of EU migrants were of working age in 2012, compared with 66% among nationals.

What about 'social dumping'?

Finland's Viking Line hired cheaper workers from Estonia

France especially has highlighted "social dumping" as a key issue for the EU to tackle, but it is a worry for other countries too. The phrase means bringing in cheap workers from other countries who undercut local workers, and who can even deprive locals of jobs.

Two European Court of Justice rulings in 2007 made it easier for firms to defy local trade union pressure and employ cheaper workers from abroad. The Laval case concerned Latvian workers posted to building sites in Sweden, and the Finnish ferry company Viking Line got backing for its hiring of Estonians.

In October 2014, a French court ruled that Ryanair had to pay €8.3m, ruling that it had broken local labour laws by employing more than 120 staff on Irish contracts in Marseille.

The EU's posted workers directive is now under review. The existing rules let firms pay social contributions in the country of origin - and those payments are often cheaper than in France. Belgium has also accused Germany of "social dumping" by giving low-paid "mini-jobs" to East Europeans.