Bosnia: How to drag a country out of the mire?

- Published

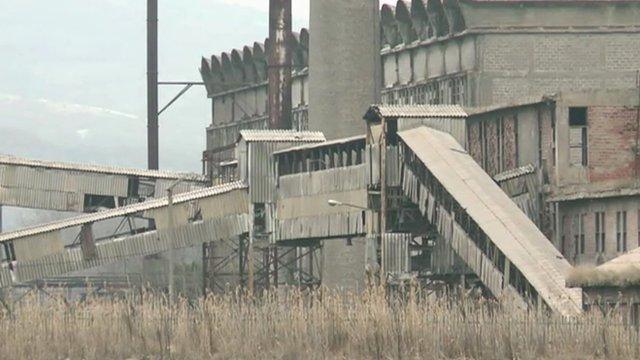

Tuzla was the first place that Bosnian anger exploded in violent protests, recently

The world must have been tempted to forget about Bosnia. It was a protagonist in a conflict apparently resolved two decades ago - only the exploits of its footballers have made international headlines much since.

But then, at the start of February, Bosnians announced that all was far from well. Demonstrators burned government buildings around the country, exasperated after years of grinding poverty and desperately high unemployment.

The initial, explosive outpouring of anger in Bosnia may have passed. But the protests continue every day. And so do efforts to find a way to drag the country out of the mire.

The focus is on the country's politicians. But most of the initiatives for change are coming from citizens who regard those leaders with contempt.

Director Haris Pasovic, a veteran of the siege of Sarajevo, says foreign leaders must bypass Bosnia's political class

Rotten system

Small groups gather in the main towns every day at noon to voice their dissatisfaction at a system under which officials are paid many times the average monthly salary of 400 euros. They complain the politicians live in comfortable villas and enjoy the use of official cars, but do little to alleviate the plight of citizens struggling to cover the basics of food, housing and heating.

But the ire of the protesters is not reserved for domestic leaders. They also hold outsiders responsible for doing nothing to correct a system which has been failing for years.

"Europe: we are the ones with whom you should talk," reads a placard that has become a familiar sight at demonstrations outside Sarajevo's fire-blackened government buildings. It reflects the feelings of many people sick of seeing international officials liaising with politicians they view as corrupt.

"The international community is not innocent in this story. They have to stop talking to the leaders of the parties," says theatre and film director Haris Pasovic, a veteran of the siege of Sarajevo, who put on festivals in the city while it was under attack.

"The biggest power is in the hands of the international community. It has been complacent in the economic destruction of the country. The IMF, the World Bank and many other organisations have been co-operating for years with the politicians. They could have imposed their rules on them, but instead they were pumping their money into a rotten political system and class."

.jpg)

Many would rather the international community spoke directly to them than local leaders they distrust

.jpg)

There is a sense that the international community forgot Bosnia after the conflict ended

Mirroring actions elsewhere, protesters torched a local government building in Sarajevo on 7 February

This is the issue which really grates with many Bosnians. They say that politicians never seem to go short, while important institutions like the National Museum are forced to close through lack of funding.

A short walk across central Sarajevo, the Museum of Literature and Art is still open - but struggling. Its director, Sejla Sehabovic, rubs her arms and apologises that the heating is off to save money.

"I lead a national museum and we have no finance. If they sold just one official car from the Ministry of Culture, we could pay everyone here a year's salary," she says.

Ms Sehabovic is from Tuzla, the northern industrial town where the recent series of protests started. Thousands of people there have lost their jobs following a series of botched sell-offs of formerly state-owned companies.

Still awaiting miracle

They have been outraged by the lack of response from the government, and frustrated that the complicated system put in place by the Dayton Peace Agreement nearly 20 years ago, remains operational.

There are three presidents - one for each major ethnicity (Bosnian Muslim, Croat and Serb) - and 14 prime ministers across the two political "entities" of Bosnia - the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Croat and Bosnian Muslim) and Republika Srpska (the ethnic-Serb region).

It is a situation which seems guaranteed to ensure that little gets done.

"It's like people woke up from a dream that someone would come to save us," says Sejla Sehabovic, director of Sarajevo's Museum of Literature and Art

Sejla Sehabovic says Bosnians have reached their limit.

"It's like people woke up from a dream that someone would come to save us. During war no-one came to save us and 20 years later we were waiting for a miracle - that the EU would say: this constitution is stupid, we'll make a new one for you. We finally realised that's not going to happen."

The citizens of Tuzla and other towns have been holding regular "plenums", where people queue up to voice their grievances, or make proposals for change.

"At the beginning there were so many requests only the law of gravity was off the agenda," says Boro Kontic, director of Mediacentar Sarajevo, an organisation which promotes independent journalism.

Gradually, the plenums have refined their demands, focusing on reducing pay and privileges for officials. But the participants admit there is little they can do to change the bigger problem - Bosnia's cumbersome constitution.

"Dayton isn't our responsibility," says Sejla Sehabovic. "We didn't write 'Dayton One' and I don't want to write 'Dayton Two'. Whoever did that has the responsibility to change it."

Valentin Inzko, International High Representative in Bosnia insists Bosnians must find their own solutions

Local ownership

But so far there has been little sign of an outside intervention. Theoretically, the International High Representative could intervene. Previous holders of the post such as Paddy Ashdown used their powers to remove ineffective officials and centralise certain functions of the state.

The current incumbent, Valentin Inzko, admits that "people on the streets tell me I'm too soft." But he says the days of acting as the "Viceroy of Bosnia" have gone.

"The international community is more in favour of the philosophy of 'local ownership'. We always stress local responsibilities and local solutions. We have done a huge job, but later we relaxed a little bit [and] said it is time that the responsibility should be taken over by local leaders and the population."

In fact, far from calling for a new constitution, the International High Representative is one of the most enthusiastic proponents of the citizens' plenums.

"Maybe for the first time a general ownership philosophy is materialising. The international community should not interfere but allow this local movement to ripen," Mr Inzko says.

Plenty of protesters will be disappointed by this attitude. Others may be relieved that it seems there will be no meddling by outsiders this time. And with elections to be held in October, perhaps the time for transformation has come.

"We have to sit down and think of what can be changed - not just what can be burned," says Sejla Sehabovic.

"I hope that by the time of the elections we will have our requests clear, and whoever gets to power will not be able to do what they did up to now."

- Published10 February 2014

- Published7 February

- Published7 February 2014

- Published7 February 2014

- Published8 February 2014

- Published24 February 2014

- Published7 February 2014