Ukraine: Europe’s major test

- Published

Pro-Russian activists held a concert in Sevastopol to celebrate the results of the Crimean referendum

The week ahead will test Europe's resolve and its ability to act over Ukraine.

One senior official in Brussels said: "It is going to be a major test of European unity post-Cold War."

The EU has warned Russia of "consequences" if it does not engage in serious dialogue and pull back its forces. The EU will discuss moving to sanctions against Moscow.

So, on Monday, at a meeting of EU foreign ministers and later in the week at a EU summit they will have to ratchet up the pressure on Russia.

So far the EU has made a gesture: it has suspended talks on an economic pact with Russia and an easing of visa restrictions. In Moscow those measures have been seen as little more than irritants.

Both the US and the EU have said they will not recognise the result of the referendum in Crimea.

French President Francois Hollande said he would not recognise "this pseudo-consultation". British Foreign Secretary William Hague said "the time has come for tougher restrictive measures to be adopted".

Dilemma

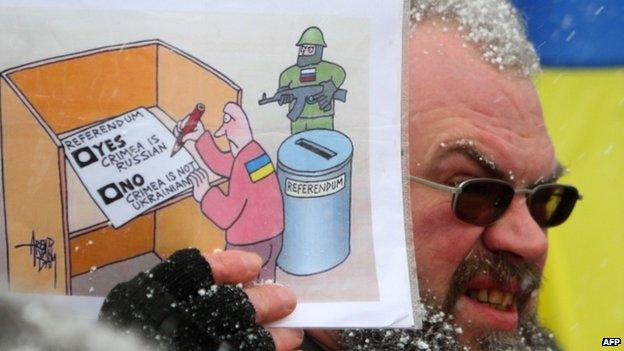

The European Union describes the referendum in Crimea as "illegal"

On Sunday, EU ambassadors met in Brussels to discuss a list of names who could be subject to an asset freeze and a visa ban.

It is the first test of the EU's intent and the outcome will not really be known until the foreign ministers meet on Monday.

Here's the dilemma: should the list just be of people related to the takeover in Crimea or should it target the inner circle around Russian President Vladimir Putin?

Should it include cabinet or key officials in the Russian parliament who have supported annexing Crimea?

Not surprisingly, among 28 countries, there are divisions. One official said bluntly if you don't go after people in Moscow you are showing a weak hand. Others argue that you cannot impose bans on people you will sooner or later have to negotiate with.

'Massive damage'

If an asset freeze and visa ban does not rattle Moscow or Russia makes further military moves into eastern Ukraine - then the EU has already warned of moving to another stage which would involve economic sanctions.

Angela Merkel is one of the EU's key players in drafting the bloc's response to President Putin's Russia

That is the real weapon in the EU's armoury.

Last week, German Chancellor Angela Merkel warned of "massive damage to Russia, economically and politically". Russia is the EU's third-largest trading partner.

Already, just in anticipation of sanctions, there are reports of Russian companies taking money out of western Banks and of individuals repatriating cash.

The Russian economy is vulnerable. Its borrowing costs are rising. Some of the world's biggest banks are said to be reducing credit lines to Russian clients.

The value of the rouble is falling and the equities market has fallen more than 24% since the year began.

What makes the EU cautious is economic self-interest and - to a degree - energy dependency: 30% of the EU's natural gas comes from Russia.

The German chief executive for the large energy company, EON, warned against "thoughtless damage to Russian ties".

Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski said: "I do not believe Russia can use it (energy) to put us under pressure. Moscow needs our money."

Eurasian idea

In truth, the EU can only really put economic pressure on the Kremlin if it is prepared to accept some damage at home - and that is difficult when so many EU countries are still struggling to find growth.

EU exports to Russia in 2012 amounted to 123bn euros (£103bn; $171bn).

Germany has forged an economic special relationship with Russia that has proved enormously beneficial to its export sector.

More than 6,000 German companies trade with Russia. In one poll, two-thirds of the German people opposed sanctions.

The EU could go after the heads of the big Russian giants like Gazprom and Rosneft or isolate the Russian banking sector.

There would be retaliation - but EU ministers have to decide whether their credibility outweighs their commercial interests.

Ms Merkel and others in Berlin, at the outset of this crisis, believed progress could only be made through dialogue and not by punishment. The German government wanted to set up a contact group with Russia.

So far, that has not happened and Germany and the EU will have to review how it deals with President Putin in the future.

He has set out a vision of a Eurasian union - which would include Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan - a competitor to the EU for influence particularly in Eastern Europe.

The EU going forward will have to review whether it is too dependent on Russia for energy. Whether EU officials realised it or not they have got drawn into a much bigger and more dangerous game that pressing for enlargement.

So, this week the challenge for the EU must be to show resolve and unity. Any divisions will be exploited by Russia. Resolve will be to deliver on consequences warned about.

'Our land'

The EU and the US are still trying to get Russia to engage with the new government in Kiev that is drawing up constitutional reforms to protect the rights of minorities. But the road to negotiation becomes harder.

Some 70% of Russians have been persuaded that Russian speakers in Ukraine are in real danger. Many Russians share Mr Putin's emotional attachment to Ukraine and believe this is a struggle against fascists in Kiev.

Compromise becomes more difficult, and if Russian forces enter other parts of Ukraine it may well prove impossible to prevent conflict with all its wider consequences.

One afterthought: there is a strong current running in Brussels that the EU over Ukraine made a strategic error.

As officials now admit, the drafting of the association agreement with Ukraine - which was the trigger for the current crisis - was largely left to technocrats.

Yet, perhaps careless of Russia's history, it involved pulling Ukraine into the European orbit. As one official observed "we never had a substantial debate over where we think Ukraine belongs?"

He went on to bemoan that there was no big debate as to how Russia would react to all this.

In Berlin, too, there are mutterings of regret, that some EU foreign ministers were too supportive of the Ukrainian opposition.

The EU has invested strongly in building a new more democratic Ukraine - now it has to stand by the new administration in Kiev whose defence minister said on Sunday "this is our land and we're not going anywhere from this land".