European elections: Too poor for a dress in Spain

- Published

Dressmaker Marta earns a little each year at Feria time

By the time Europe elects its new parliament this month, the women of Seville will have put away their flamenco dresses for another year.

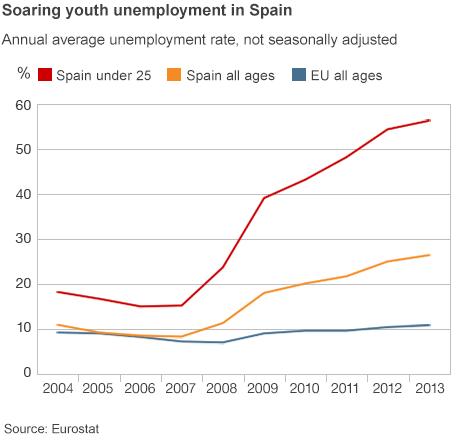

In a region where female unemployment stood at 38% last year, there will be some who could not attend the Feria, southern Spain's great, unavoidable, week-long show and traditionally the social event of the year for rich and poor alike.

Some will have the consolation of knowing that they managed to scrape together the cost of sending a daughter this year, covering costs that can reach hundreds of euros for a single day of socialising - perhaps with the help of a special Feria bank loan.

Others may continue to maintain the fiction that they were fed up attending Feria, so preferred to stay away.

Either way, a major part of Spain's heritage is quietly being eroded six years into the economic crisis.

It adds to the sense that the country is falling into decline, dropping further behind its eurozone partners to the north.

Do Spain's unemployed women see a political answer?

To try to send an angry new voice of protest to Brussels and Strasbourg? Or to vote again for the devil you know, perhaps, in the hope that a long-established party like the Socialists has learned the lessons of the debt crisis?

'Killing us'

"The Popular Party?" Mili ponders incredulously when I ask her as she leaves the job centre if she would ever consider voting for the centre-right party that returned to power in Spain two-and-a-half years ago. "No. They are killing us."

Mili has still to decide which party she will vote for

She will vote, she says, but has not made her mind up yet.

Now 50, she lost her job as an auxiliary nurse in an old people's home four years ago, when the Socialists were still in power. Separated from her husband, she has two grown children, one of whom is in work.

Angelica, 45, says she will vote Socialist. "The Popular Party like the rich," she says, outside the same job centre near Seville. "That's no good. The Socialists like the working people."

The Socialists, the unemployed barwoman argues, spent too much money only because they wanted to help the poor, although, she adds, "there was corruption too".

Divorced, with two children aged 18 and 22, she gets 426 euros (£350; $591) a month in benefit, while her retired parents help with their pensions too.

Driven

When Carmen Yusta, 34, lost her job as a teacher because of government cuts, politics suddenly got personal.

Former teacher Carmen Yusta says the capitalist system is absolutely broken

Now a candidate in the European elections for the new radical protest party Podemos, the unemployed Seville woman says she is driven on the one hand by personal anger over her own sacking and on the other by indignation at the rate of unemployment in her country.

Placed 20 on the party's candidate list, she is unlikely to make it to Brussels but will be glad to raise the profile of Podemos, which draws its strength from leftist street politics.

"The object is not the 25th of May," she says about election day (for most of the EU), when we meet at a party to celebrate the opening of an alternative social centre in a Seville squat.

"We will start a movement on 26th May to change everything in Spain and Europe and the world because the capitalist system is absolutely broken. We have to do something from the south of Europe to resolve this situation."

Maca, a lifelong anarchist, has never voted in any election

Try telling that to Cadiz woman Maca, 35, who has been unemployed for four years but is active in alternative community work in Seville - like the inauguration of the new social centre squat.

"I think that when you are inside [the political system], you are not allowed to change things any more," she says.

"It's important that new anti-capitalist parties exist but I don't think they can really change things."

A lifelong anarchist, Maca has never voted in any election and will not change now, she says.

Buy, borrow, swap

Politics, like the other business of Seville life, will be conducted chiefly among the cabins of the Feria for now.

While not officially unemployed, artist Marta de Marte lost the work she enjoyed before the economic crisis, when she created accessories for museum shops in Madrid.

Now she earns a little each year at Feria time as a dressmaker, when she does alterations for Seville women too poor to afford a new dress but conscious that Flamenco fashion is ever changing.

"Feria is like a window on Seville, so people really feel the need to show off," she says, showing me a dress that is 30 years old.

Marta Gonzalez right, irons flamenco dresses in her laundrette

Marta Gonzalez, who manages a Seville laundrette, is hard at work ironing flamenco dresses for its customers at 30 euros apiece.

"If you don't have money to buy a dress, you might borrow a friend's or a sister's or swap," she says.

"You can use a dress from five or six years ago. You don't have to buy a new dress every year. But if you have no money..."

There are "quite a few" women Marta the artist knows who are not going because they cannot afford it.

And then she remembers a local proverb: "Two kinds of people go to the fair - those who ride and those who eat the dust from the road."

This report was compiled with the help of social psychologist Lucia Sell-Trujillo, who has been studying the effects of austerity , externalon people's lives in Seville.

You can also follow Patrick Jackson's reporting on Twitter, external and read more in his blog on Tumblr, external.

- Published1 May 2014

- Published30 April 2014

- Published26 April 2014