Germany's youth rebels against EU

- Published

Members of the AfD, Germany's first Eurosceptic party in decades, protest against Angela Merkel

Euroscepticism is taking hold even in the country at the heart of the European project. And one of the continent's chief Eurosceptics, British politician Nigel Farage, has become an idol to some young Germans - to the consternation of many others.

For rebels, they appear extremely polite, are impeccably dressed and display a distinct lack of piercings or tattoos.

Germany's Junge Alternative (JA), or Young Alternative, may be dissidents - a Eurosceptic youth movement determined to overturn Germany's long-standing pro-European orthodoxy - but they are very conservative ones, advocating a crackdown on immigration and crime.

In fact their stance has earned them a particularly bad rap from the national press. In the short year since the group's launch last June, the JA have repeatedly been accused of being "too far right", external, politically regressive and anti-feminist.

The organisation is linked to the country's first Eurosceptic party in decades, the Alternative fuer Deutschland (AfD), or Alternative for Germany, which wants the euro broken up.

But it remains an independent movement and even the groundbreaking AfD regards it as something of an unruly offspring.

"The media sometimes portray the AfD as far-right and, because we are more direct and more right-leaning than the AfD, we're seen as extreme-right - but that's not the image I have of us," says Sven Tritschler, the JA chairman for North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany's most populous state.

The state's biggest city, Cologne, was the starting point for the AfD's European election campaign on 27 April. A fifth of all party members are based in surrounding North Rhine-Westphalia, and the AfD is hoping to further increase its support here.

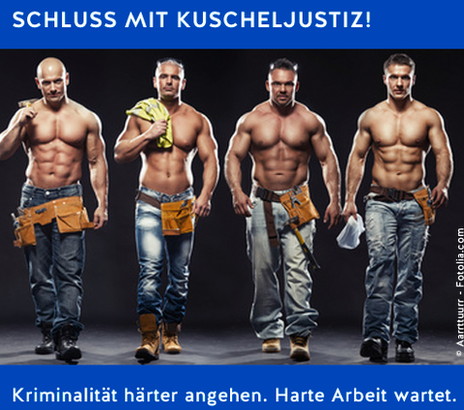

"Equality instead of uniformity": German media failed to see the cheeky humour of the JA's European election poster, calling it sexist and in bad taste

In response, the JA used four half-naked men in its new anti-crime campaign demanding an end to "soft justice"

Wary of journalists

The negative press has certainly made the party wary of journalists, which might explain why Mr Tritschler turns up with no fewer than six other JA members to meet the BBC in Cologne.

"They were curious about what you want to know," he says. "We might regret it later."

Junge Alternative is a Eurosceptic youth movement inspired by UKIP's Nigel Farage

Aged between 17 and 32, the small gathering is typical of the JA: male, degree-educated and part of a growing number of young people "concerned about Germany's future within the European Union".

Statistics show that some 20% of under-30s voted for fringe parties, including the AfD, in last year's general election, compared with only 7% in 2005.

The AfD seems to be providing an attractive alternative for those unhappy with Germany's political consensus. And research shows the AfD/JA is doing especially well among the young.

As German journalist Tilo Jung points out, "for ages there was no option to cast a vote to the right of Chancellor Angela Merkel's Christian Democratic Union, unless you voted for the far-right. The AfD provides that now."

The German Eurosceptics are highly critical of the EU's bailout policies, demanding the dissolution of the euro, a halt to EU expansion, and national immigration quotas.

But they strongly reject accusations of extremism. The JA's national leader Philipp Ritz says the JA also has "more liberal" attitudes, like supporting giving asylum seekers the right to work.

"Don't bother joining if you're looking for racism or homophobia," adds Mr Tritschler.

Unlikely hero

Instead, the JA is looking to British Eurosceptic leader Nigel Farage for inspiration.

Nigel Farage was the star guest at a recent conference organised by the Junge Alternative (JA), or Young Alternative

His anti-euro United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) is also expected to score a good result, external in the May ballot, potentially beating mainstream parties.

The youth organisation invited Mr Farage to speak at a conference in Cologne in late March.

Mr Farage's appearance sparked a deluge of negative headlines and soured relations with AfD chief Bern Lucke who called the move a "sign of poor political tact".

"There are significant differences between the AfD and UKIP," he said.

Mr Lucke has repeatedly sought to distance himself from right-wing populism ahead of the European elections, where his party is expected to reap around 7% percent of the vote.

If successful, the AfD will need to join a pan-European faction in order to make its voice count.

The official party line is that they will opt for the group of conservative reformists, which includes Britain's governing Conservative Party.

As a result, Mr Lucke does not want to spoil his chances by "tainting his reputation" with uncomfortably close UKIP ties, says political expert Kai Arzheimer.

"However, the question remains whether they'll eventually give in to the temptation of playing the right-wing populist card, which would hold a brighter electoral future for them, because immigration is going to be an issue for Europe in the long term," he notes.

'Interesting character'

Mr Tritschler is unapologetic about courting Mr Farage.

"One of the main reasons for people joining the JA is that we try to speak and think without political correctness," Mr Tritschler says.

"Somebody who's been exercising that for quite a few years in the European Parliament is Nigel Farage and that's why we invited him. He is a Youtube star for a lot of people and he's an interesting character."

Although the JA does not support Mr Farage's push to leave the EU altogether ("We are in the midst of Europe while he is on an island in the North Atlantic so we can't have the same solutions"), it does find resonance in his criticism of the EU apparatus and his anti-immigration views.

"We are all sitting on a train called the EU and we are constantly accepting new passengers without knowing where it's actually heading," says Mr Ritz.

The group also believes the EU should have its political powers curbed, and become once again an economic community.

While all eyes are on the EU elections, the JA says the real prize will be getting into the German parliament, the Bundestag.

"That's where all the main decisions are made, especially concerning Europe," emphasises Mr Tritschler, adding: "The European parliament is the most powerless parliament in the world."

- Published7 May 2014

- Published27 August 2013