Le Pen family tiff a test for France's National Front

- Published

Marine Le Pen publicly criticised her father for making a "political mistake"

The National Front (FN) is a family business. It thrives on the cult of personality, of the Le Pens.

The founder and patriarch, Jean-Marie, funds the FN from his personal fortune. Marine, his youngest daughter, has taken it further mainstream than many might have thought possible.

But this week an extraordinary row blew up between father and daughter that has brought the party to a pivotal moment between its uncompromisingly far-right heritage and the newer "FN-lite" that Marine has engineered.

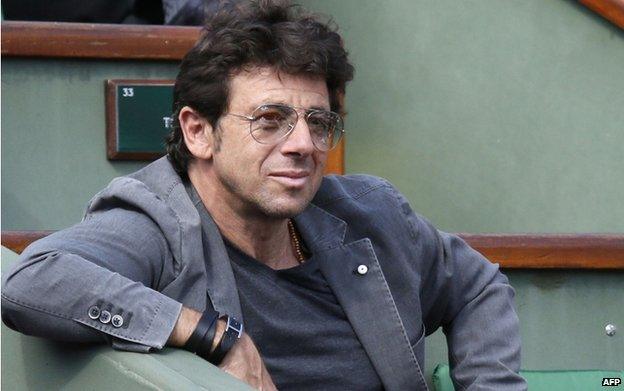

In a video diary posted on the party's website, Mr Le Pen was questioned about the singer and actor Patrick Bruel, who is Jewish. "We'll include him in the next batch," said Mr Le Pen, using the word "fournee" - which has been interpreted as an oblique reference to the ovens of the Nazi death camps.

Mr Le Pen has made anti-Semitic remarks before. He has criminal convictions for inciting racial hatred. Last month, before the European elections, he suggested the deadly virus Ebola would solve the global "population explosion" and, by extension, Europe's "immigration problem".

Political commentators viewed this as Marine's first big test: how she handled it, they suggested, would reveal her true beliefs, whether the party had really changed.

Patrick Bruel said Mr Le Pen had given a reminder of his "true face"

The immediate response was to remove the video blog. Marine, while claiming her father's comments had been interpreted maliciously, also said, "But given Jean-Marie's very long experience, not to have anticipated the way these words would be interpreted was a political mistake."

Mr Le Pen's outbursts follow a well-tested formula. Whenever the spotlight shifts from him, he bounds back into it with a crude, controversial remark. The media laps it up. So, it seems, does a growing, disillusioned part of the electorate. To his hardline supporters he is "pure", undiluted by the pursuit of power.

"To criticise a Jew, or to respond to a Jew's criticism, is not anti-Semitic," he told the French newspaper Le Monde. "They are citizens like anyone else. When they attack you, you retaliate without fear."

In an open letter - "a peace offering" to the party - he adds: "I am not a court darling. I react to things in my own way, with my own temperament."

That has been the secret of the FN's success. It has stood apart from France's stale political mainstream. Marine has played on her image as an outsider, derided by the political elite.

I visited a village in north-eastern France that has a peculiar claim to fame.

Not one voter in Brachay, in the Haute-Marne, opted for France's two main parties at the European elections. Of Brachay's 28 voters, 22 chose the FN and another three opted for the anti-EU Front de Gauche party.

The mayor and nearly all villagers in Brachay support the FN

The mayor, Gerard Marchand, a dairy farmer, had in the past voted for the centrists, the UDF, and then the Socialists. Nothing had changed as a result, he felt. And so two years ago he, along with 500 mayors nationwide, gave his signature to Marine Le Pen's anti-EU presidential campaign.

"We are fed up with all other parties," said Mr Marchand.

"They are incompetent and dishonest. We started in Europe with five, six, seven countries...today we are 28. And now we have Eastern Europeans taking our jobs. France is for the French.

"In this country, if you have leftovers on the table then you give them to the neighbours, but first you have to look after your own!"

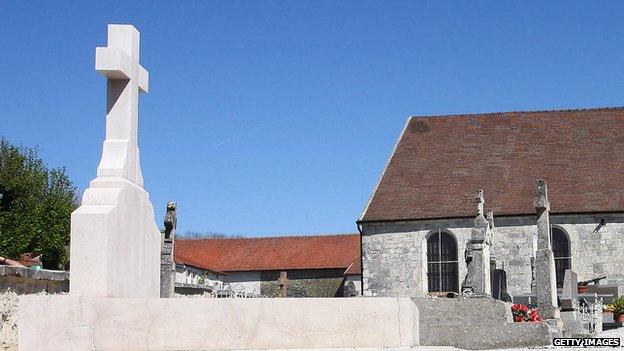

Charles de Gaulle's grave is simple, belying the stature of one of France's most prominent presidents

Not many miles away is Colombey-Les-Deux-Eglises, the former home and resting place of the legendary statesman Charles de Gaulle. His tomb is a simple one, belying the stature of the man.

Visiting the grave was Clement, a young Frenchman who yearns for a leader like de Gaulle.

"Great speeches, great ideas, great vision - we don't really have that any more: someone who inspires us with a collective vision for the country," he lamented.

Marine Le Pen's supporters would argue she reflects some of the fighting spirit of de Gaulle. She has proved a strong leader, with a plan, and with a united party - three things you can't say of her rivals.

Her new focus is the 2017 presidential election. She is winning the working-class vote in cities and in villages like Brachay where the old certainties are disappearing.

Privately she must wonder whether her father's "temperament" will ruin things. Asked on radio whether he had now fallen out with Marine, Mr Le Pen harrumphed: "Mmm… No comment."

Vice-President Florian Philippot is seen as part of a new group in the party

He sees the party he built as his personal possession, an extension of himself. Some say he's jealous of his daughter's success, perhaps won at the expense of the way he ran things.

There is in the leadership a new group of more moderate intellectuals, teachers, and civil servants. Vice-President Florian Philippot, for example, an alumnus of the prestigious ENA training school for France's elite, or Philippe Martel, Marine's chief of staff and once an adviser to Alain Juppe when he was foreign minister.

There are also hints that Marine wants to leave the "old" FN even further behind. She has created her own brand, Blue Marine, which some suspect may be the first step to changing the name of the party.

For the moment, the row probably suits them both. Jean-Marie rallies his core support among party hardliners. Marine, meanwhile, gets more column inches in which to argue that the "new" FN genuinely is different and can be trusted.

National Front

1972: Founded by Jean-Marie Le Pen

1986: Enters parliament

2002: Jean-Marie Le Pen comes a shock second in presidential poll, beating Socialist candidate

2011: Marine Le Pen succeeds her father as head of the party

2014: Wins European elections in France with almost 25% of the vote

Will voters believe her? An online survey for Le Point - which is anecdotal at best - suggests 80% of the French think she has indeed reacted in the right way to her father's outburst.

But going forward, she faces a formidable political juggling act. If she edges too close to the mainstream, the party's support risks being co-opted by the traditional right.

At the same time, can she really carry on with her father as honorary party president? He, and his outbursts, will eventually limit how far she can go.

It is a headache, as are so many father-daughter rows. He pays the bills, after all, and is a generous party donor. If the row goes any deeper, then it won't be so much a tiff as a very messy family fall-out. There may even be talk of disinheritance. And it could leave her 2017 ambitions in tatters.

- Published16 May 2014

- Published17 May 2014

- Published14 May 2014

- Published13 May 2014