Germany Riesending cave rescue: Test of human limits

- Published

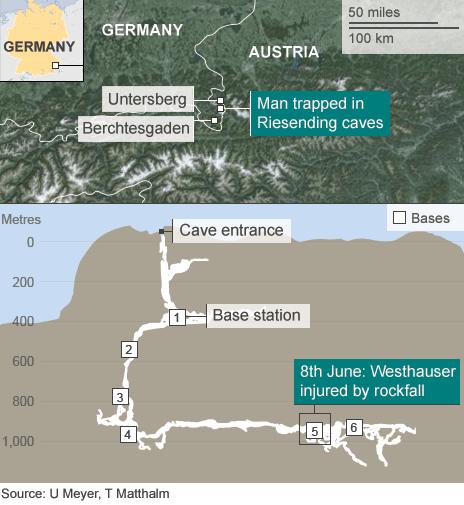

It was a laborious, stop-start process to transport Johann Westhauser via a series of rest stations

It has been literally inch by inch through the most difficult conditions, in Germany's deepest cave. The limits of human tolerance of heights and the tightest of confined spaces have been tested.

On his journey from the bottom of a 1,148-metre (3,766ft) deep hole, Johann Westhauser has been strapped into a protective casing - the word stretcher doesn't do it justice.

He has worn a white helmet with a visor, which was pulled down over his face when he was squeezed through crevices so narrow that his nose was millimetres from the rock face.

At one stage, he was winched up through a cavern 300-metre high - laborious, stop-start progress to the surface via a series of five rest stations or bivouacs set up to give him medical care and just to let the rescuers get their strength back.

The condition of the injured man is not known, though it does seem to be better than first feared.

A Bavarian doctor in the rescue team described it as "stable" and "relatively good". He is thought to have suffered a brain injury of unknown gravity in the rock fall nearly two weeks ago - so he has a brace to keep his neck and head from moving.

Crews are navigating a rescue operation in Riesending cave

According to the German media, however, he has been able to keep one arm free of the stretcher to help with the pushing.

Major shortcomings

The doctor, who is one of those involved in the rescue, said the biggest problem was the narrowness of some of the passages.

Rescuers from a number of countries were involved in the operation

"It's not like being in an ambulance where I have space and I can move but the doctors are always with the patient and have everything they need."

The team has been multinational. The Riesending complex is near the German town of Berchtesgaden on the border between Bavaria and Austria, so Germans and Austrians have been involved but also Croats, Swiss and Italians because of their expertise in similar deep caves.

This one is particularly deep and treacherous. Riesending means "giant thing" in German because of its vastness.

It was only discovered in 1995, and it is hard to imagine that the small hole in the ground through which the explorers - and now the rescuers - entered actually opens out into a complex of caves, rivers and tunnels stretching for 19.1km.

The scale of the complex has meant a rescue operation involving 200 specialists and tens of helicopter flights each day with supplies to the cave entrance.

As the victim neared the surface, questions were being raised about who would foot the bill, which might run into the hundreds of thousands of euros.

Cavers are encouraged to take out insurance but their association in Germany has said that this does not always cover the cost of a rescue.

"Unfortunately, the insurance policies existing today have major shortcomings in terms of their coverage of what are often very high costs," the association says.

It estimates that the most which is usually retrievable from insurance is 2,500 euros (£2,000; $3,397), while it reckons that the true cost can be as high as 40,000 euros (this was clearly written before the current rescue).

Because of the shortfall, the association set up a "solidarity fund" to help its members out. Each contributes 26 euros and then has access to the fund. The difficulty is that the solidarity fund currently, according to its website, holds 37,000 euros. This will not be enough.

Thrill of exploring

Mr Westhauser works at the Institute for Applied Physics at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, but it is not known if he went into the complex (as he has done many times before) as part of his research or as a hobby.

There are sound scientific reasons to explore caves.

Arachnologists, for example, seek rare breeds of spiders deep underground because they have a special history. which is different from spiders found above ground.

They can yield information about evolution. In Laos, for example, scientific cavers have discovered spiders with fewer than the usual eight eyes.

But there are cavers, too, who do it for the thrill of going where no human may have trod before. It is a genuine sense of exploring the unknown, spiced with the thrill of danger.

When George Mallory was asked why he wanted to climb Everest in 1923, he replied: "Because it's there." He died in the attempt, by the way.

Whatever Johann Westhauser's motive was, it has turned out to be an expensive exercise, both in terms of money but also in terms of the sweat and risk expended by the people who have pulled him out.

- Published12 June 2014

- Published10 June 2014

- Published10 June 2014

- Published9 June 2014

- Published17 July 2012

- Published25 May 2012