Gavrilo Princip: Bosnian Serbs remember an assassin

- Published

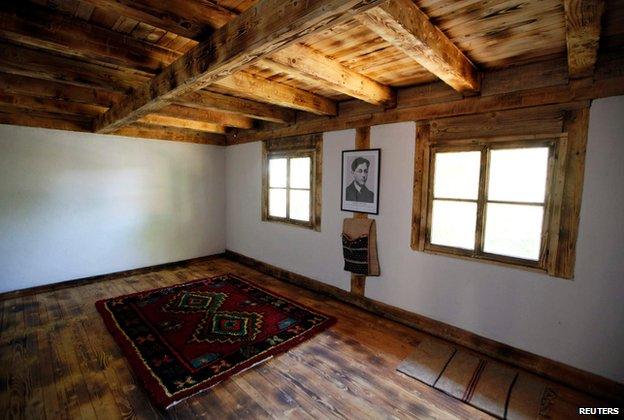

The house in eastern Bosnia where Gavrilo Princip was born has been renovated and opened to the public

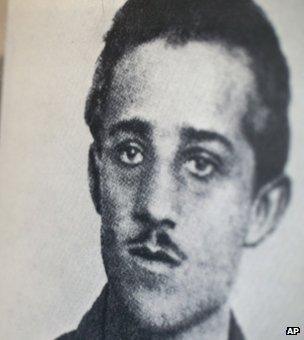

During preparations to mark 100 years since the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the BBC's Guy De Launey found Bosnian Serbs in eastern Sarajevo paying tribute to the 19-year-old man whose actions triggered World War One.

East Sarajevo seems a world away from notions of Hapsburg emperors and an idealistic assassin who fired the shots that ignited World War One.

Boldly coloured but otherwise identical mid-rise concrete blocks line the largely treeless streets. Cyrillic signs indicate that the visitor is in Bosnia's ethnic-Serb "entity", Republika Srpska.

But on an unpromising patch of land, fully exposed to the fierce Balkan summer sun, workers are sweating over a tribute to the man who brought Austro-Hungarian influence over Bosnia to a violent end.

They are rushing to complete a small municipal garden in which the centrepiece will be a statue of Gavrilo Princip, the young Bosnian who shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914.

The few passers-by stick to the shade at the perimeter of the park. But, when asked their opinion of the subject of the statue, they light up.

An unassuming plinth and a small municipal garden were prepared for the statue in East Sarajevo

"Historically, Gavrilo Princip was an important person," says a man emerging from a decorators' shop. "He used to play an important role in our society and then suddenly that changed."

"I think Gavrilo Princip deserves to have his monument erected," says a woman walking past with plastic bags of shopping.

Princip and the shot that sparked WWI

Gavrilo Princip was one of seven members of Mlada Bosnia (Young Bosnia), a Bosnian Serb militant organisation which wanted independence from Austria-Hungary

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and wife Sophie shot dead in their car by Princip on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo

Austria responded angrily and declared war on Serbia, securing unconditional support from Germany

Russia announced mobilisation of its troops

Germany declared war on Russia, 1 August

Britain declared war on Germany, 4 August

A short walk away in the municipal town hall, Mayor Ljubisa Cosic offers highly alcoholic apple rakija and a voice of reason.

"There are many different discussions about his role and his act," he says. "Our opinion is that he was not a terrorist. He had revolutionary ideas of liberty, not just for Serbs - he belonged to the Slavic movement."

Local Mayor Ljubisa Cosic argues the statue should not be seen as provocative

In the former Yugoslavia - the pan-Slav state which emerged from World War One - that would have been a reasonably uncontroversial statement. But following the ethnically charged Balkan conflicts of the 1990s, Princip, as a Serb, has become a far more divisive figure.

Still, Mayor Cosic insists that the erection of a statue to the assassin should not be viewed as an act of provocation to Bosnia's other ethnic groups.

"Erecting a Princip statue is not an act against reconciliation," he says. "I have my own view of history - so do my citizens - and they view Princip as a hero."

The view could hardly be more different in the centre of Sarajevo, some 20 minutes' drive away.

Many of the buildings here date back to before 1914 - a daily reminder that Bosnia was once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. For some of the Bosniak Muslim majority here, Princip's shot was the start of the country's descent into tragedy.

"The consequences of his action were very bad for Bosnia," says Fedzad Forto, an editor at the news agency of the Bosniak-Croat ethnic entity.

"Bosnia ceased to exist in Yugoslavia, and Bosnian Muslims were not recognised until 1968."

Fedzad's view is that Princip was a terrorist - an uncontroversial position in Bosniak parts of the country, where the assassin is largely viewed as an ethnic Serb nationalist rather than a pan-Slav idealist. Even pointing out that Austria-Hungary was an occupying power fails to persuade Princip's critics that he helped to liberate Bosnia.

The shooting took place on a street corner near the Latin Bridge in Sarajevo

"They were still much better rulers than the kingdom of Yugoslavia or communist Yugoslavia," says Fedzad of the Hapsburgs. "You can look at the historical records and see how Austria-Hungary cared about issues like the rule of law. We lost so much in 1918."

So the commemorations in the centre of Sarajevo will take on a completely different tone to those in the east of the city. The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra will visit and play, in front of City Hall, a selection harking back to Hapsburg days, including Haydn's Emperor Quartet.

The concert will end with an extract from Beethoven's ninth symphony - since adopted as the anthem of the European Union. Fedzad Forto admits a display of unity would be better for his country than the rival commemorations.

"We should join forces to commemorate the victims of the war - and make new common ground, not more divisions."

But that is not going to happen. Princip's pan-Slav dreams are further away now than they were a century ago.