Eurozone crisis: The grim economic reality

- Published

- comments

The European Central Bank can expect more pressure as clouds continue to gather over the EU economy

Over recent weeks, the French government has been saying it would "tell the French the truth" about the economy. A new reality is dawning.

French Finance Minister Michel Sapin has spoken of Europe's "economic malaise". After another quarter of zero growth in France, he has admitted that the government's previous forecast of 1% growth this year is impossible to reach.

It is not just France where uncomfortable truths have been unveiled. In the second quarter of the year, Germany suffered a 0.2% decline in GDP.

An important survey earlier this week concluded that economic growth will be weaker in 2014 than expected.

Italy is back in recession and the French economy stagnant. Other countries are hinting they will cut their growth forecasts.

And the risk of deflation is growing. French consumer prices fell 0.4% month on month. Portugal's price index slumped 0.7% in July. Spain saw the steepest slide in consumer prices in five years.

French Finance Minister Michel Sapin says there is "economic malaise" across Europe amid poor growth

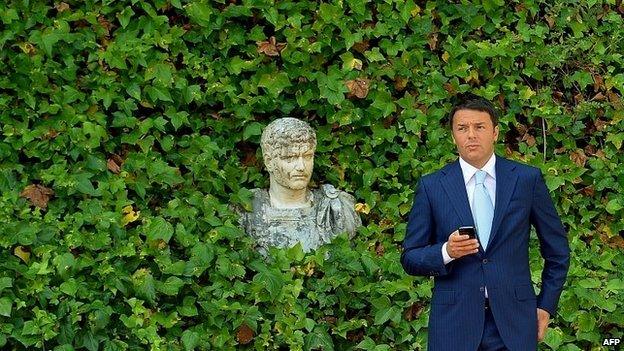

Falling inflation and non-existent growth also puts countries like Italy in crisis. Matteo Renzi's young administration has been marked by great energy.

The Italian prime minister said that "not even dictators managed to get things done as fast as this."

But the dramatic far-reaching structural reforms to overhaul the labour market and the bureaucracy are not in place.

And here is the nub of the Italian crisis: it has debts of 2.1 trillion euros (£1.7 trillion). The debt-to-GDP ratio is currently edging towards 136% and rising.

That figure is likely to rise further and the fear is that at some stage the markets will ask how Italy will service its debt. To stabilise the debt, the country would have to run a very strong primary surplus, which is most unlikely.

Uncomfortable times

France is not only slashing its growth projections but signalling it will miss its target for reducing its public deficit as agreed with the European Commission. The deficit will end up above 4% of GDP, missing the 3.8% target.

The French, in a new spirit of candour, are saying they will cut the deficit "at an appropriate pace". It sounds like saying: "We will interpret the rules in our own way."

Mr Sapin said: "We must adapt the pace of deficit reduction to the exceptional situation... of growth that is too weak everywhere in Europe and the exceptional situation of inflation that is too weak across Europe."

It could make for an uncomfortable period.

There is a lot of frustration with France, particularly in Germany, for its failure to meet existing targets. There may well be resistance to further flexibility.

Italian PM Matteo Renzi administration is energetic but has been unable to introduce much needed reforms

In Italy, Mr Renzi said this week: "I have absolutely no interest in breaking the 3% ceiling."

But make no mistake - the arguments over the Growth and Stability Pact will be back in play this autumn. The French and the Italians will become even more vocal about relaxing rules.

However, there are some bright spots.

The Spanish economy has benefitted from a surge in exports. It may even revise up its growth forecasts. Unemployment has been falling too, but even so it remains at 24.5%.

Greece has a budget surplus but its economy is still shrinking. It may find some modest growth later in the year, but even so its projected growth remains too weak to significantly reduce its mountain of debt and, almost certainly, it will need further help.

Russian sanctions biting

The eurozone economy is also being buffeted by external crises, principally Ukraine.

It is hard to calculate the impact of sanctions against Russia, but at a moment when the European recovery is so fragile they are a further unknown. Some German manufacturers are hurting. German exports to Russia dropped 14% in the first four months of the year.

Greece could see some modest growth this year but its economy is still shrinking

Some European leaders, like French President Francois Hollande, are looking to the European Central Bank (ECB) to ride to the rescue.

"The ECB must take all necessary measures," Mr Hollande said, "to inject liquidity into the economy."

The ECB has already implemented six new long-term financing operations, in which banks are required to sign up to commitments to lend more. And banks which want to deposit reserves with the Central Bank have to pay negative interest rates.

The ECB says it stands ready to do more and is committed to using "unconventional instruments."

The pressure on the ECB is likely to grow but a much bigger question hangs over the European economy: why is growth so elusive and how will it bring down the high levels of youth unemployment and debt?

- Published30 July 2014

- Published23 July 2014