Catalan independence push faces big hurdles

- Published

Tom Burridge reports on the independence movement for Catalonia

As Scotland prepares to vote on independence, Catalans and Spaniards are watching with a mixture of excitement and unease.

Despite cries of "illegal" from Madrid, Catalonia's top politician is committed to holding a similar vote in this Spanish region, the BBC's Tom Burridge reports from Barcelona.

For those in the Catalan pro-independence camp 2014 is an important year.

First, it is the 300th anniversary of the end of the siege of Barcelona, when Catalans celebrate their national day.

"La Diada", as it is known locally, has to the annoyance of some in Catalonia become a show of force for the Catalan independence movement.

A week later Scots head to the polls in a historic referendum, and pro-independence Catalans will be watching closely, as their president plans a similar vote on 9 November.

In the Yes camp

Catalonia's president: "Can you stop forever a democratic movement of an old nation of Europe?"

On the eve of La Diada, Catalonia's President Artur Mas told me he would be staying up late into the night on 18 September to find out the result of the Scottish referendum.

"Personally, I want a 'yes' vote," he said.

Why? Because Mr Mas is "100% certain" that an independent Scotland would be accepted into the 28-nation European Union.

He believes that would prove that the same would happen if Catalonia were to gain independence from Spain.

That said, the Spanish Prime Minister, Mariano Rajoy, has previously suggested he might block Scotland's entry into the EU.

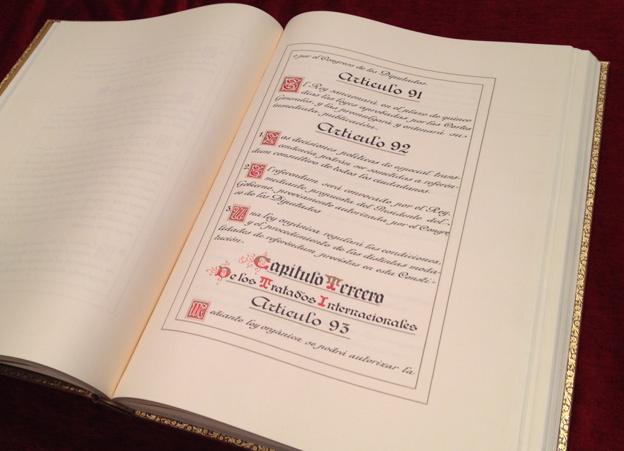

BBC's Tom Burridge looks at the Spanish constitution's rules for calling a referendum

Legal wrangling

In a matter of weeks, Spain's Constitutional Court is expected to rule that a referendum in Catalonia would be "illegal".

Mr Mas seems unperturbed, claiming that a "non-legally binding vote" would still be possible under Catalan law.

When asked what a "yes" vote in such a case would actually mean, his answer was unclear.

But that perhaps reflects the fact that no one really knows, because it would be uncharted territory, with the territorial integrity of Spain at stake.

What about if the Catalan government were offered a "third option", of more powers, or a new economic settlement with Madrid, via some form of constitutional change?

Artur Mas said he would accept such a deal, as long as the terms were open, and voted upon by the Catalan public.

"Democracy first," he told me.

Article 92 of Spain's constitution puts Madrid in control of referendums

On the eve of Catalonia's national day a pro-independence march took place in Barcelona

'Right to decide'

Those in Spain, and in Catalonia, who are now actively fighting against Catalan independence and a referendum on the subject, believe the pro-independence camp has shifted the debate, from one about secession to one about the Catalan public's so-called "right to decide".

Jose Juan Toharia, from the Spanish polling company Metroscopia, says "the subject (of independence) has become very confused".

Who would not support the concept of "the right to decide", he argues.

"It has been in a success in semantics of the independence movement."

From his name, Marcus Pucnik doesn't sound Catalan or Spanish.

But this son of a former Slovenian politician, who now works for the Catalan equivalent of the Scottish "Better Together" campaign, firmly proclaims he is both.

"It is not a good thing to have a referendum in which people are forced to define themselves as either Catalan or Spanish. People are mixed," he says.

His organisation's real name is Catalan Civil Society.

The group "would never support" a referendum on Catalan independence, he tells me.

"But we would accept it if it was legal, and within democratic margins, and guaranteed a free and fair vote."

Linguistic identity

Marcus believes the pro-independence movement in Catalonia has hijacked Catalonia's national day, which before was simply a celebration of Catalan history and culture.

The Castell - a human tower - is a Catalan tradition

"We are called traitors, or anti-Catalans, when in fact we are both very Catalan and very Spanish."

For some, like Mireia Maymi, 30, the desire for independence comes from a mix of identity and economics. She is studying the art of dubbing films and TV series into Catalan - the predominant language in the region - over Spanish.

"If you have a language you structure your mind with this language, so you think differently."

She believes Catalan schools and hospitals suffer because of a raw funding deal from Madrid.

"There are things that happen here that are being decided in Madrid. This is not logical," she says.

But the polls point to a more complex picture.

According to a recent survey, conducted by Metroscopia, 43% of Catalans would support independence from Spain, 42% would support staying as part of Spain, with the rest "undecided".

However, when told that Catalonia would automatically remain outside of the EU, the percentage supporting independence fell to 38%, while 53% favoured remaining part of Spain.

Most interesting of all, when people were given a third option of constitutional change, involving more powers shifting from Madrid to Barcelona, then 44% preferred that option, with the number supporting independence falling to just 23%.

'Pujol' factor

There is a "P" factor also to bear in mind.

In recent weeks, it has emerged that Jordi Pujol, the former Catalan president, and possibly the region's most famous politician of all time, has millions of euros in bank accounts in Andorra.

The Spanish press is awash with allegations and stories of corruption, and the Metroscopia poll found that more than half of those Catalans interviewed believed that the case against Jordi Pujol had damaged the independence movement.

However Manuel Cuyas, a journalist who transcribed Jordi Pujol's memoirs, believes the case will damage the political party of Artur Mas and Jordi Pujol, but not the independence movement itself.

Artur Mas, a friend, colleague and (at least formerly) an admirer of Jordi Pujol, told me he was "personally very disappointed".

In a candid admission, Mr Mas said "politically, it is a blow".

However, Catalonia's president said, it did not fundamentally change things.

His campaign for a Scottish-style referendum goes on.

- Published21 August 2023