Russia's gas fight with Ukraine

- Published

Russia wants Ukraine to pay for gas bills dating back to late 2013

After several rounds of tough talks a deal has been reached - through EU mediation - for Russia to resume gas supplies to Ukraine.

It is critically important for Ukraine as the harsh winter looms - as well as for many of its East European neighbours, who also rely on Russian gas.

Russia cut off Ukraine's gas in June as the conflict between the government in Kiev and pro-Russian rebels in the east escalated.

Why did Russia cut off Ukraine's gas?

Russia moved on 16 June to turn off the taps, after complaining that Ukraine had failed to pay off its debts, estimated at $5.3bn (£3.3bn; 4.2bn euros) by Russian state-run giant Gazprom. Gazprom had sought a repayment of $1.95bn.

It was not the first time: it cut supplies because of price disputes in 2006 and in the winter of 2008-09. Those earlier disputes led to gas shortages elsewhere in Eastern Europe, meaning hardship for many ordinary citizens in mid-winter.

In the tug-of-war between Russia and the EU over the future direction of Ukraine, the current gas row has been harder to resolve.

Ukraine's winter gas supplies were last turned off in January 2009

Why is gas so important?

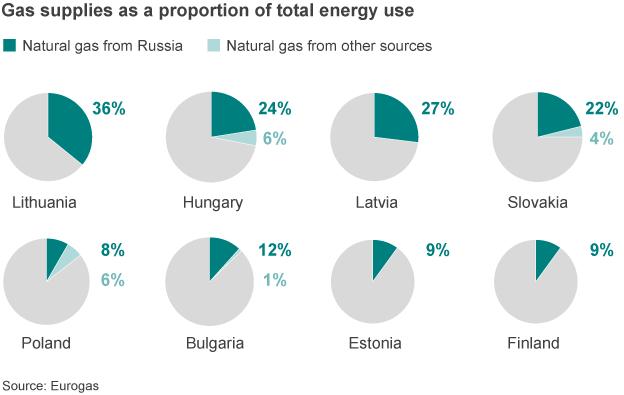

Ukraine, until the current crisis, relied on Russia for half its gas supplies. Some EU member states such as Slovakia take all their gas from Russia. In total, Russia supplies 23% of the EU's gas.

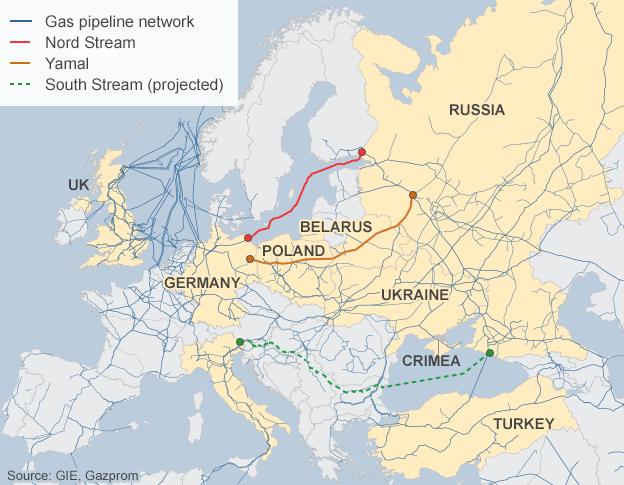

Russia's supply lines run through Ukraine to several EU countries and as much as 70% of its gas to the EU is carried through those pipes. So while Russia has in recent years tried to bypass Ukraine, in particular with the Nord Stream and South Stream projects, the two countries are, for now, inextricably linked.

Has Moscow tied its gas supply to the crisis in Ukraine?

The supply and price of Russian gas have been part of this crisis from the start.

In December 2013, Ukraine's then-President Viktor Yanukovych enraged protesters by signing a deal for cut-price gas in Moscow weeks after he ditched an agreement for closer ties to the EU at the last minute.

Several gas pipelines have been attacked during the conflict in eastern Ukraine

In April, the government in Moscow then raised the price by 80%: initially it went up from $268.5 per 1,000 cubic metres (cu m) to $385.5 because of unpaid bills, then up to $485, much higher than the market level, ostensibly because of the introduction of an export duty on gas.

Ukraine said the only reason for the price rise was politics although Gazprom insisted it wanted its bills paid and offered a lower price.

However, there was concern in September when gas supplies to Poland, Slovakia and Germany mysteriously dropped. This was seen by some as a warning signal not to extend EU sanctions on Russia, and also not to sell on to Ukraine some of the gas it was receiving from Russia.

What has been agreed now?

Ukraine will make two payments this year to clear most of its gas debt: a $1.45bn tranche "without delay", then a $1.65bn tranche.

This debt settlement will be based on the price of $268.5 per 1,000 cubic metres (cu m).

The EU agreed to act as guarantor for those payments.

Next year the rest of the debt is to be paid off - that quantity of debt and the gas price are to be determined by an independent court.

When the dispute erupted, Russia and Ukraine both took their cases to the international arbitration court at the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce. A final decision is only expected next summer.

Russia agreed to resume gas deliveries to Ukraine, for which Ukraine will pay monthly in advance.

These new deliveries will cost Ukraine $378 per 1,000 cu m to the end of 2014, and $365 in the first quarter of 2015.

Ukraine is free to order as much gas as it needs, the European Commission says., external

How does this affect the rest of Europe?

With winter ahead, urgently sorting out the gas row was seen as a key reason why the EU delayed implementation of a free trade deal with Ukraine until January 2016.

Russia has strongly opposed the free trade deal, arguing that Ukraine could become a back door for cheap EU goods to flood into Russia. So delaying it could be seen as a concession to Russia.

After carrying out a series of "stress tests" on 38 European countries, the EU has warned that any prolonged disruption of Russia's gas supply could leave private households "out in the cold". Worst hit would be Finland and Estonia and the non-EU Balkan states of Serbia, Bosnia-Hercegovina and Macedonia.

The Baltics, Slovakia and Hungary are among other EU states that rely heavily on Russian supplies.

But the European Commission says , externalif countries work together rather than adopting "purely national measures" then fewer consumers would be hit.

Although Russia can avoid supplying Ukraine directly, several EU countries have passed on part of their gas supply to Ukraine through a process known as reverse flow.

Can Russia avoid sending its gas through Ukraine?

That is what it is trying to do - but it takes time. One of its biggest projects is South Stream, which runs through Bulgaria and Hungary, among a number of EU states.

Can Ukraine gets its gas elsewhere?

Ukraine's Prime Minister Arseniy Yatseniuk has secured several gas deals with neighbouring countries

Since Ukraine's Russian supply was cut off, it has worked hard to find alternative European providers in Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Poland. Slovakia's Eustream has pledged to provide Ukraine with 10bcm of gas per year, external while Germany's RWE predicts, external it will supply a similar amount.

Norway's Statoil has signed a deal but has refused to disclose the volume and cost, apparently to avoid harming its efforts to tap the energy fields of the Arctic. Hungary was also providing Ukraine with gas until it announced in late September it was ending the practice.

How much more does it need?

Ukraine consumes about 50 bn cubic metres (bcm) of gas per year, producing about 20bcm but importing the rest. Gazprom officials believe Ukraine needs 18bcm to heat its population during the winter.

While the figures are unconfirmed, Ukraine's gas transit authority says it has stored 16.7bcm of gas underground.

It has succeeded in buying in supplies from several neighbours but still needs about 5bcm from Russia.