Turkey's Erdogan battles 'parallel state'

- Published

President Erdogan said the corruption allegations implicating his immediate circle were lies

The voices sound crackly.

"Are you at home, son?"

"Yes."

"They carried out an operation. Their homes are being searched now… take everything in the house out."

"There is your money in the safe."

"That's what I'm saying."

It was a recording that changed the course, no less, of modern Turkey.

Those who posted it a year ago say it revealed the then Prime Minister, now President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan instructing his son to hide stashes of cash after police raided other ministers' homes.

It formed part of the biggest corruption scandal, external in this country's recent history, Mr Erdogan and his inner circle implicated, it seemed, in massive embezzlement.

Stories swirled of the general manager of a state bank hiding €4.5m (£3.5m) in shoe boxes.

An Iranian businessman was accused of laundering €87bn with the help of the authorities by circumventing sanctions against Iran.

For many, 17 December 2013 will be remembered here for generations to come.

Dark forces

Mr Erdogan hit back. The recordings, he said, were lies and full of "montage".

He spoke of dark forces at work, a so-called "parallel state" seeking to topple the elected government.

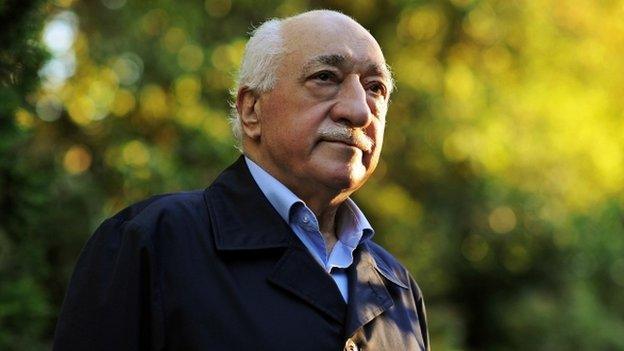

The man behind it, he said, was cleric Fethullah Gulen, once a close ally, now a fierce opponent, living in self-imposed exile in Pennsylvania.

Over these 12 months, the "Gulenists" have become public enemy number one.

Declared a national security threat, the government has waged war on the "parallel state", firing thousands of police officers, prosecutors and judges who it says were working for Mr Gulen.

It meant a second wave of arrests, due on 25 December, was never carried out by the new police leadership.

Yasin Topcu was deputy chief of the financial crimes unit; a senior figure in the investigation. On 18 December, he was removed from his position.

Mark Lowen looks at a turbulent year in politics for Turkey

"In a coup, you hide what you're doing from parliament but we gave all our evidence and reports to parliament to investigate," he says.

"Turkey has bad memories of coups so the government played on that because it didn't want people to know what was really happening."

Will the facts ever be found out, I ask.

"In the short-term, people might be fooled by these lies and manipulation," he replies, "but after a while they'll see the truth and react."

Media clampdown

Stage two of the government clampdown was on the media it deemed a threat.

YouTube and Twitter were blocked, a decree later overturned by the constitutional court.

Mr Erdogan spread his version of events in a press that he's ensured is heavily pro-government.

And, last weekend, Gulenist media were raided, over 20 journalists and production staff arrested from the opposition paper Zaman and Samanyolu TV.

It prompted the ire of the EU, which called it "against European standards and values".

Mr Erdogan lashed out, telling Brussels to mind its own business.

"The allegations were so serious that the government took an authoritarian direction to confront them," says political commentator Cengiz Candar.

"If they had been treated as they should in a democratic country, the government would not have survived. It shows Turkey is not yet a consolidated, functioning democracy."

Turkey now ranks just 154th of 180 countries in the press freedom index of the watchdog Reporters without Borders.

And concerns have grown that free expression is under assault as the government closes ranks, relying on loyalists.

Criticism from human rights groups, international media or Western governments is framed as a baseless attack on Turkey, a conspiracy to undermine a country that won't tow the western line.

The pliant media environment has allowed a gagging order to be imposed by the government, banning reporting on the corruption enquiry set up by parliament, due to wrap up later this month.

Some speak out

Just a few papers said they would not obey.

Cihan news agency is one of the remaining critical media - but it fears it could be targeted next by the wave of arrests.

Its head, Abdulhamit Bilici, tells me Cihan's reporters have been prevented by the government from covering the presidency or prime ministry for the past few months and that pressure has been put on advertisers to cancel their contracts with the agency.

"In a normal democracy, freedom of expression should be encouraged - it should not be a life and death issue," he says.

Opponents accuse Erdogan of stifling free speech

"The label "parallel state" is a claim to silence people with different opinions.

"I am doing my job; if there are wrongdoings by anyone, I must report it. The accusation is baseless."

But despite the turmoil of the past twelve months, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has won two elections, external since December 17: local and presidential.

He's arguably the most powerful leader since the Turkish Republic's founding father, Ataturk.

And everything he does and says is geared directly towards the more conservative half of the country that supports him; if the other side doesn't, in his view, it's their loss.

His success is based on two key issues: huge economic growth under his leadership - Turkey rising from the financial crisis of 2001 to the 17th biggest economy - and his staunchly pro-Muslim rhetoric, encouraging girls to wear the headscarf at schools and universities, where they were previously banned.

Loyal following

He has built up such a loyal following that many of his supporters have never doubted his narrative of what happened last December.

"Turkey has one of the most free media in the world" insists Ibrahim Yildirim, a businessman who believes last year's allegations against the government were invented.

Fethullah Gulen is a a fierce opponent of the president

"This country has always had corruption - but after he came to power, it's decreased. There is a group within the police getting orders from somewhere else - and I don't like it."

I ask what Mr Erdogan means to him.

"He's my hero. Look at the economy: we have stable growth. If his party stays in power, we'll have a bigger, richer country."

For student Zeynep Ilham, the president is "just a person - he makes mistakes like everyone but he's under a lot of stress".

"He and his party have a certain sensitivity towards Islam - and that's why the majority of Muslims in Turkey vote for him," she says.

But the events of 17 December will leave a lasting impact.

They stunned a seemingly omnipotent leader, creating a new "enemy within" here.

Zeynep Ilham supports the president

They radically changed the image of Turkey's leadership abroad. And they further deepened divisions in an already profoundly polarised Turkey.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan is this country's great political survivor.

But he has also created an extraordinary chasm at the heart of Turkish society.

And for his critics, that will be his legacy.

- Published15 December 2014

- Published20 November 2014

- Published24 March

- Published7 January 2014