Hitler's old house gives Austria a headache

- Published

Bethany Bell visits the house where Adolf Hitler was born

What do you do with the house Hitler was born in? For years the building in the Austrian town of Braunau am Inn has been rented by the Austrian interior ministry to prevent misuse by neo-Nazis.

It was once a day-care centre for the disabled. Now it is empty, as the owner has not agreed to any plans for its future use.

Braunau am Inn is a pretty little town in northern Austria, right on the border with Germany. But it has a heavy legacy.

Just off the main square is Salzburger Vorstadt 15: a solid, 17th-Century former inn, where Adolf Hitler was born in 1889.

Hitler's family, who rented rooms upstairs, was not originally from Braunau. His father Alois, had been posted there for his job as a customs official.

Adolf Hitler only lived in Salzburger Vorstadt 15 for a few weeks, before his family moved to another address in Braunau.

They left the town for good when Hitler was three years old. He returned briefly to Braunau in 1938, on his way to Vienna, after he annexed Austria to Nazi Germany.

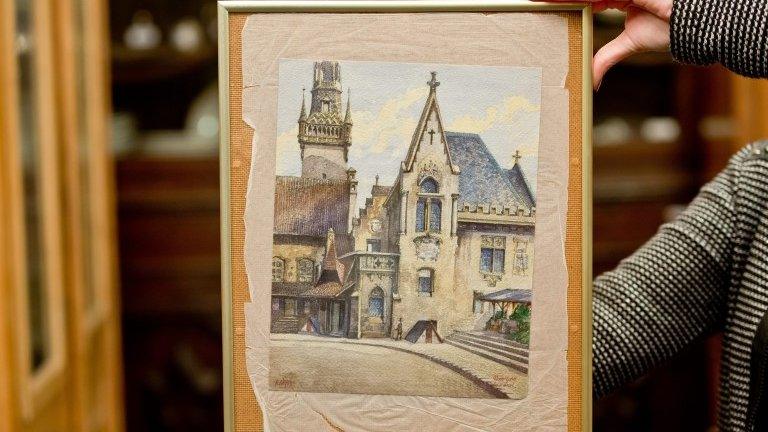

Hitler visited Braunau after Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938

Locals say the house still attracts some neo-Nazi sympathisers.

"I've even witnessed people from Italy or from France coming here… for adoration purposes," Josef Kogler, a teacher in Braunau, said.

"One Frenchman, a history teacher I think it was, came and asked me for Hitler's birthplace… It's hard to understand."

These days, the house is locked up and empty.

The Austrian interior ministry was so concerned about the possibility of neo-Nazis using the building as a site of pilgrimage that, since 1972, it has rented it from the owner, Gerlinde Pommer, to prevent any misuse.

Mrs Pommer currently receives almost €5,000 (£3,925; $6,140) a month, according to town officials.

For many years, the house was used as a day-care centre for people with special needs. But in 2011, they had to move out.

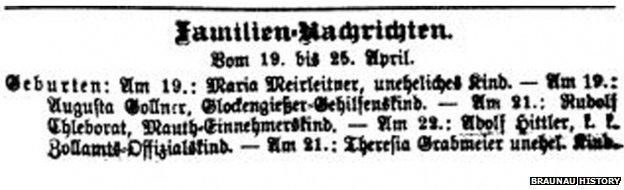

A cutting from a local newspaper in April 1889 records the birth of 'Adolf Hittler'

Florian Kotanko, a local historian, says Mrs Pommer will not agree to renovations.

"She does not accept any proposal of using the house for offices or other purposes," he said.

"She does not allow any changing of the house, so you can't rebuild any rooms, you can't build modern bathrooms or put in a lift. It is difficult."

Over the past three years, various proposals have been put forward about how to use the house.

These include turning it into flats, a centre for adult education, a museum or a centre of responsibility, for confronting the Nazi past.

One Russian MP even offered to buy the house and blow it up.

Historian Florian Kotanko says Austrians have learned to speak frankly of their past

With no agreement in sight, the interior ministry recently appealed to all the other federal and regional government ministries to help decide what to do with the house.

Braunau's deputy mayor, Guenter Pointner of the Social Democrats, says the ministry is now considering terminating the rental contract with Mrs Pommer. She was not available for comment.

The row over the house has stirred up uncomfortable memories for the prosperous little town.

Some, including Braunau's second deputy mayor Christian Schilcher of the far-right Freedom Party, think it is time to move on.

"The people are fed up," he said. "This theme is a problem for the image of Braunau. We want to be a beautiful little town, with tourism and visitors. We are not the children of Hitler."

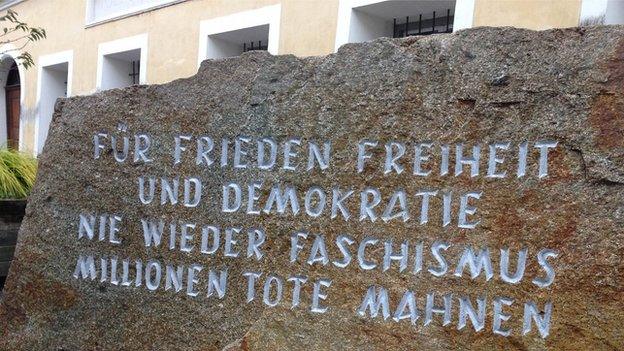

A stone plaque outside Hitler's birthplace honours the victims of fascism

But others, including Florian Kotanko, say ignoring history makes things worse.

"You have the connection with Braunau and Hitler even without the house," he said. "Everyone can read that Hitler was born here."

Braunau now has plans to put up an exhibit about the house and the links with Hitler in the local museum.

For many years, Austrians and the people of Braunau were reluctant to discuss the Nazi past, but Florian Kotanko says that is changing.

"Once people refused to talk about the facts... but now they speak about it," he says. "It's a matter of how to deal with the heritage."

- Published27 March 2012

- Published22 November 2014

- Published30 March 2012