Europe in 2015: A year of insecurity

- Published

As in previous years, Europe enters 2015 with worries about its economy

For Europe, 2015 will witness another attempt to reach a place of safety. For the past two years European officials and leaders have declared the economic crisis over. In the past six months a sense of foreboding has returned.

The dangers are not the same as 2012. There is no danger of countries being unable to fund their debts. The threat now is of stagnation and deflation.

European officials have warned time and again that the failure to create growth and new jobs risks not just social tension but support for the European project. Currently the economy will not return to its 2007 level until 2020.

In 2015 economic recovery will be uneven. Demand is chronically weak. Germany will remain the engine room of the European economy but will not be the powerhouse it was two years ago. Growth in France will be around 0.7%. Italy should edge away from recession but the eurozone is not expected to achieve growth of more than 1% and that will not be enough to dent an unemployment rate that remains at 11.7%.

Once again eyes are turned towards the President of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi. Sometime in the first three months of the year he is expected to turn on the taps, boost demand and buy sovereign bonds. It may not be straightforward however. There is opposition in Germany; there may well be legal challenges and there are doubts over what impact all of this will have.

Anti-austerity movements

Europe still seems to be placing its bets on keeping the value of the euro low and relying on cheaper exports to boost demand at home.

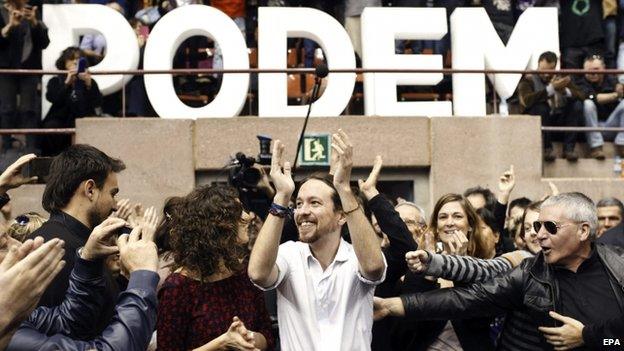

Could Spain's anti-austerity party Podemos take power in elections in 2015?

Popular discontent with austerity is growing. Once again there are likely to be tensions between Berlin, which continues to demand deficits be reduced to below 3% and reforms are made to labour laws, and Paris and Rome, which believe Europe needs growth and investment in large-scale infrastructure projects.

2015 will once again give the anti-establishment parties the opportunity to mine Europe's discontent. There are elections where these insurgent parties may play key roles. Within weeks Greece could be voting with the radical left-wing party Syriza, who are currently ahead in the polls. If successful, the party would be looking to restructure its debts and it would raise fears that the Greek crisis might return.

Later in the year Spain will got to the polls. It, too, has a fast-charging radical left party called Podemos which is fiercely anti-austerity.

And in Britain in May, the United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) may have a say in any post-election bargaining for power.

One of the key factors in undermining support for the mainstream parties is unemployment. In France the number of people looking for work has reached a record high. In November the unemployment figures rose by 27,400 to 3,488,300. The numbers looking for a job have risen by 5.8% in the past year. This threatens the political future of President Francois Hollande. Unless his administration can start creating jobs in 2015 he will become a lame duck president and that plays into the hands of Marine Le Pen's Front National.

In France, President Hollande is under pressure from Marine Le Pen's Front National

2015 will also test whether the former French President Nicolas Sarkozy not only has a firm grip on his party but whether the French people might give him a second chance.

In Italy, Matteo Renzi is facing popular opposition to his reforms but the test will be whether those reforms are watered down and whether they are rigorously implemented.

The mood in Italy is fragile; a country which has seen little growth in the past ten years. Two of the country's opposition parties are openly anti-EU with one pushing for a vote on staying in the euro.

Immigration concerns

No issue reflects the volatility of the European mood more than migration and immigration. Once again the summer months will see large numbers of people fleeing instability in the Middle East and Africa trying to cross the Mediterranean to reach Europe.

"Anti-Islamisation" protests in Dresden have rattled Germany

Mainstream politicians will struggle with this challenge. Germany, which has taken in far more refugees from the Middle East than other countries, has recently been shaken by protests. Just before Christmas 17,500 people marched in Dresden under the banner "Patriotic Europeans against the Islamisation of the West". There were protests in other cities. The German political establishment has been shocked by these street protests and political leaders have appealed for "understanding and openness".

What this demonstrates is that concerns about migration are not confined to Britain. In many European countries it is a potent political issue that is contributing to the rise of anti-establishment parties. Europe's leaders have yet to discover a convincing response.

Europe will wait with some anxiety to discover the outcome of the British election. One senior European official said the UK - after the European economy - will be the central European question for the next three years.

If David Cameron stays in office it is expected that discussions will start in the second half of the year on what his re-negotiation shopping list will look like - ahead of an in/out referendum on EU membership in 2017. At the European Council meeting in June he will be expected to set out what he broadly wants. He will face both a desire to keep Britain in the EU but an unwillingness to offer concessions that makes the UK a special case or which undermines the fundamental principles of the EU such as freedom of movement.

It remains unclear what the process for these negotiations will be. Some European leaders are hopeful changes can be made via secondary legislation but ultimately it seems likely that a British re-negotiation might require treaty change.

Some countries, like Germany, believe that treaties will have to be changed to support the new architecture of the eurozone. They believe the EU is already at the margins of what is permissible under the treaties. But there is little appetite to call an inter- governmental conference and France, in particular, will oppose any steps that lead to a referendum.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron is looking to change the UK's relationship with the EU

So for the UK the road to re-negotiation will be long and winding and will be a major test for British diplomacy which, recently, has not always read the European mood correctly.

In 2015 the new European Commission will have to demonstrate it has the will and flexibility to embrace meaningful reforms. Will its 300 billion euro investment fund actually fly? Will the EU take steps towards a digital single market or energy union?

Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker is off to a confident start. He is a wily tactician presiding over a pragmatic Commission. He remains vulnerable, however, over his time as Luxembourg prime minister when companies based their companies in the Duchy to lower their tax liabilities elsewhere.

On balance he should survive because the two largest parties in the European Parliament are solidly behind him.

However Mr Juncker would be at risk if it turned out that he had been an activist prime minister, encouraging companies to embrace schemes that helped them avoid paying taxes.

The star of the new Commission looks set to be Frans Timmermans, the first vice-president. He is already emerging as an able advocate for the EU in several languages and will surely play a key role in any future UK referendum.

Russia test

Russia will remain a troubling unknown. A miscalculation in Eastern Ukraine could tug Europe towards a new cold war.

Europe's relationship with Russia remains strained over the Ukraine crisis

The Russian economy is hurting. Recently a former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin said "we have entered or are currently entering a full economic crisis".

That would hurt the wider European economy. 2015 is likely to see European unity tested again over Russia. Some countries - like France and Italy - may yet be tempted to push for an easing of sanctions.

Russia has the potential to become the dominant European story of 2015.

In interviews on the street many young people refer to themselves as the "precarious generation". In order for Europe to rediscover stability and to restore faith in the European project them the insecurities of a new generation have to be addressed.

The best sense of what is at stake came from Herman Van Rompuy, the outgoing president of the European Council. He said: "Without the UK, Europe would be wounded, even amputated - therefore everything should be done to avoid it. But it will survive. Without France, Europe - the European idea - would be dead."

Once again in 2015 Europe will face big questions about its future.

To all those who follow this blog - best wishes for the New Year!

- Published15 December 2014

- Published4 December 2014

- Published28 November 2014