Greece sent back to brink of crisis as polls loom

- Published

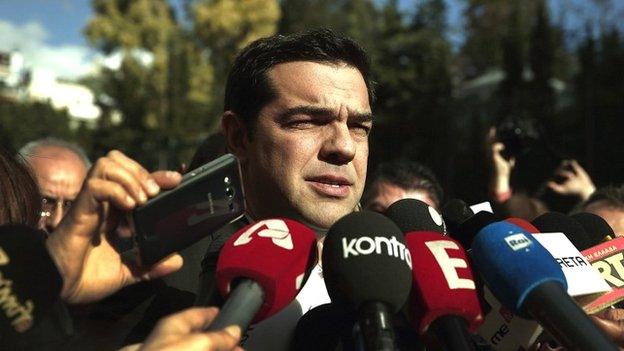

Alexis Tsipras's radical left Syriza party leads the polls and wants to renegotiate Greece's bailout

Greeks are preparing for more political turmoil, after MPs rejected the government's presidential nominee and triggered snap parliamentary elections.

No-one here knows who will form the new government, but there is a sense that this election is the latest in a long line of critical moments that have marked Greece's journey through the economic crisis.

There has been a touch of the apocalyptic in the coverage of Greece's newspapers over the past 48 hours, with the MPs' vote variously described as "Judgment Day", "the end of an era", and the government's "Waterloo".

The elections, planned for 25 January, are seen as a chance for the radical left-wing party, Syriza, to enter government for the first time.

Syriza is promising to reverse Greece's austerity programme, but what risks do its policies pose for Greece and the rest of Europe?

Imposed austerity

Greek anger at austerity is long-lived. In 2011, Athens erupted in violent protests against budget cuts tied to the second tranche of a massive bailout by the EU, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund,

From its beginnings as a coalition of leftist parties, Syriza has grown into an opposition party leading the opinion polls.

It has drawn support from Greeks who feel they are being unfairly punished by Brussels, and who complain that four years of imposed austerity have failed to deliver a recovery they can see.

Since the beginning of the bailout programme, Greece's debt has risen from 120% to 175% of GDP, and its unemployment rate hovers around 25%.

Government attempts to reform Greece's economy have been met with often violent protests

Syriza's chief economic adviser, John Milios, told the BBC that his party did not want to "continue to create enormous surpluses just for serving the debt".

"It deprives society and the economy of resources which could be used for development," he said.

Syriza says that if it wins the elections it will renegotiate the terms of the bailout, end Greece's austerity programme, and write off part of the country's debt.

Those policies are popular with many Greeks, but others worry they could derail the country's recovery and possibly even force its exit from the eurozone if Brussels decides to play hardball in negotiations with the new government.

Awkward questions

But how real are those risks?

The stock market responded to Monday's vote by falling more than 10%, though it later rebounded.

And after an initial dip in Spain and Italy, wider European stock markets appeared to be largely unaffected by the end of trading.

Economists say the measures and reforms put in place four years ago to stabilise the eurozone have helped to insulate other struggling economies.

Syriza hailed Monday's vote as a historic day for Greek democracy

Given that level of political and financial investment over the past four years - €240bn (£188bn; $290bn) to Greece alone - Syriza is gambling that Brussels will opt to negotiate a new deal on its bailout, rather than risk a Greek default at this stage.

After all, the party says, it would be channelling the expressed will of the Greek people.

And that, perhaps, is what worries Brussels more than economic contagion.

Its strategy of austerity for Europe's hardest-hit countries has led to a new surge of support for populist parties opposed to the EU's medicine.

If Syriza wins Greece's elections, it would give a boost to parties on both the far left and the far right - in Spain, Italy and elsewhere - which are pushing back against EU authority.

The risk this time around is less that markets would tar other countries in the eurozone with the Greek brush - or at least, not immediately - it is rather that other countries might follow Greece's lead themselves and choose to reject the path to recovery laid out by Brussels.

And that leaves the EU with an awkward question to ponder in 2015. In terms of EU rules and strategy, where does national democracy fit in?

- Published30 December 2014

- Published16 December 2014

- Published17 December 2014