Blasphemy, jihad and victimhood

- Published

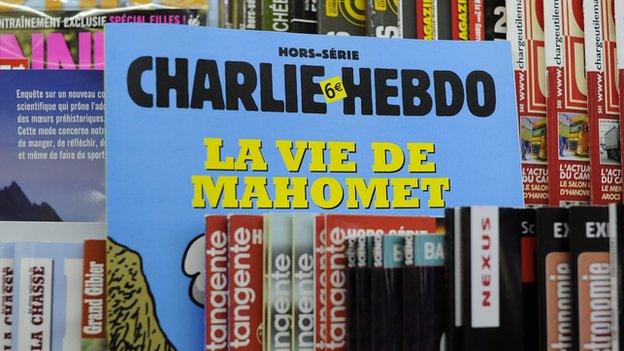

The shootings in Paris caused images of the Prophet Muhammad to be published more widely than ever before

The Charlie Hebdo murders marked a tipping point.

By selecting a target that symbolised freedom of speech, the Kouachi brothers - who killed 12 people in their 7 January attack on the satirical magazine in Paris - compelled many Europeans to take a stand.

Media houses that had declined to publish images of the Prophet Muhammad have now done so.

By exposing that much of the West's self-censorship on issues such as blasphemy has been driven not only by reluctance to cause offence but also by fear of physical attack, the brothers obliged editors and publishers to find their courage.

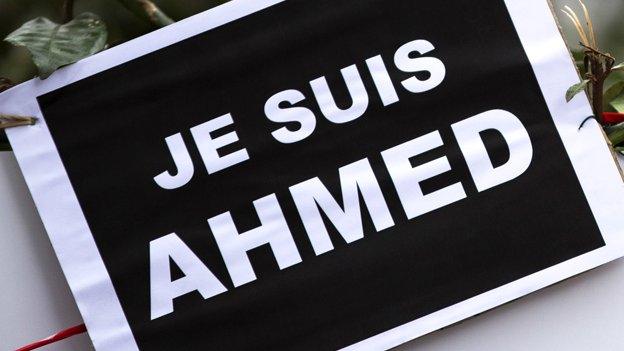

And the massive French marches showed that millions - including many Muslims - wanted to express their support for Western values.

But that can't hide the deepening divide in European societies - just listen to the number of times you now hear the words "we" and "they".

While virtually all Muslims see violent Jihadism as a perversion of Islam, there is increasing tendency in the Western media to suggest that violence might be integral at least to a strand of Islamic thinking.

Right-wing, media-monitoring blogs are celebrating the shift, praising any programmes and articles that hint that Islam is regressive.

Of course, most people still accept that the vast majority of Muslims are just as horrified and upset by militant Islamist violence as anyone else. But Muslims are under increasing pressure.

Extremist views

For years, they have routinely been asked by journalists to condemn violence. Now questions are also being asked about mainstream Muslim opinion on doctrinal issues such as blasphemy.

Many Muslims find now themselves described as extremists not because they support violence but because of their religious views.

When a shopkeeper recently told a BBC radio programme that he loved the Prophet more than his children, many of his fellow countrymen found that difficult, if not impossible, to understand.

The blasphemy issue highlights the depth of the divisions. And while blasphemy used to be conceived as an offence against God, today it's often seen as an offence against the feelings of religious people.

Freedom of speech advocates say a law against blasphemy is essentially a law against free speech

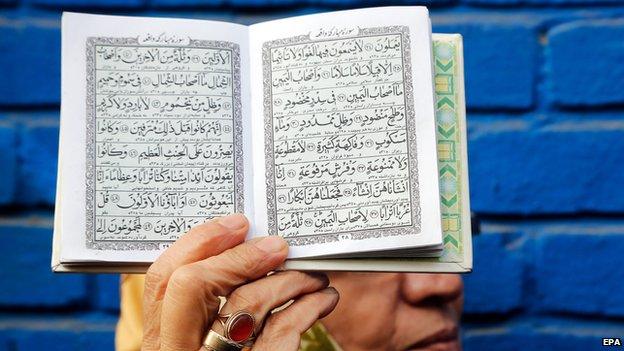

Today in Pakistan, the country with the most blasphemy cases before its courts, the most commonly alleged blasphemous offence is damage to copies of the Koran.

Those accused are sometimes hacked to death by enraged mobs.

Because blasphemy is such an incendiary issue, it is sometimes used to settle scores.

A disproportionate number of cases are brought against members of the Hindu, Christian and Ahmedi minorities. But many Sunni Muslims also get accused.

One Karachi businessman found himself charged with blasphemy, external for putting the business card of an unsuccessful job applicant named Mohammed in the bin.

When they were in power, the Afghan Taliban prohibited not only visual images of the Prophet but also foreign TV crews filming any living thing.

The restriction they claimed was in line with Islamic teachings, although the Taliban hardly helped burnish their religious credentials by making exceptions for Taliban ministers who wanted to make important statements.

Limiting free speech

While Westerners tend to view such bans as obscurantist and ridiculous, it was only 30 years ago that some local councils in the UK tried to ban cinemas showing Monty Python's religious satire Life of Brian, external.

In Ireland, long dominated by the Catholic Church, remnants of such attitudes remain in the constitution, which bans "the publication or utterance of blasphemous, seditious, or indecent matter".

In 2009 the Irish parliament passed legislation, external that spelt out the offence in more specific terms: "publishing or uttering matter that is grossly abusing or insulting in relation to matters held sacred by any religion thereby intentionally causing outrage among a substantial number of adherents of that religion".

Supporters of the clause hoped that the inclusion of words such as "intentionally" and "substantial" would underpin freedom of speech by setting out possible grounds on which to mount defences of allegedly blasphemous acts.

A woman holds up a copy of the Koran during a demonstration against cartoons depicting the Prophet

But to their dismay, Pakistan picked up the wording and proposed to the UN Human Rights Council that it be adopted internationally.

The attempt failed and, fearful of becoming model of how to limit free speech, Ireland is due to hold a referendum that would remove the blasphemy article from the constitution with a view to replacing it with legislation on hate speech.

The extent to which blasphemy and hate speech overlap is contested. Some argue that blasphemy should be stripped of its religious associations and that to insult anything held sacred by another is blasphemous.

Muslim sensitivities

But this somewhat abstruse, semantic argument risks concealing the issues at stake - should religion be afforded special legislative or even constitutional protection?

And how can religious extremists be stopped from reacting to offence with violence?

Before the cartoonists were gunned down in Paris, the only Westerners fully engaged in these questions were hard-core freedom of speech advocates.

Violent demonstrations in Afghanistan protesting against US soldiers desecrating Korans were relegated to down-bulletin stories that left many viewers baffled as to why everyone was getting so worked up.

That has changed. Blasphemy is the lead story now with political chat show hosts asking: "What is it? How come people take the issue so seriously?

And shouldn't secular West European countries worry about racist or misogynist speech as much as blasphemy?"

Such discussions almost always develop into a row about power. Political Islamists and Western liberals often argue that Muslim sensitivities about public challenges to their faith and identity are informed by the fact that over time they have been colonised, invaded, tortured and falsely imprisoned by Westerners.

The US and Israel, they argue, are the subject of so much invective and even violence because, for all their talk of human rights, they hypocritically use their own strength to oppress Muslims, whether in Iraq or Gaza. Furthermore, it is argued, Muslims are singled out for abuse.

Thus, while the Charlie Hebdo management sacked a cartoonist for anti-Semitism, it did not hesitate to publish anti-Islamic cartoons.

Demonstrators in Pakistan burn a French flag during a protest against Charlie Hebdo magazine

These arguments about the unequal distribution of power are bolstered by socio-economic surveys within Western countries. Muslims are often at the bottom of rankings measuring people's health, employability and educational levels.

Critics of political Islamism often respond to these arguments by saying - not very convincingly - that attempts to explain violent jihadism are akin to condoning it.

But they also make more substantial claims - that while Islamists exaggerate and even wallow in their sense of victimisation, they don't get so angry about the persecution of and discrimination against minorities in Muslim-majority countries.

After all, Christians in the so-called Islamic State and Shias in Saudi Arabia are even more marginalised than Muslims in Europe.

Islamism's opponents also ask whether the religion should be granted unique protections just because some of its adherents feel weak and vulnerable. Might affording Islam special protection from criticism and satire even be racist?

After all it seems to be predicated on the view that the Muslim community is incapable of responding to criticism and satire with calm, rational debate.

It all depends how you look at it. How, for example, do you interpret the fact that when the Kouachi brothers fled the Charlie Hebdo offices they yelled: "We have avenged the Prophet?" Some see that as a sign that Islam teaches not peace but violence.

But others reckon the brothers were in fact using the blasphemy issue as a vehicle to express the frustration, anger and powerlessness that come with being the sons of Algerian migrants, alienated and unable to get a fair chance in the society they were born into.

- Published20 January 2015

- Published15 January 2015

- Published8 January 2015