Spain's anti-corruption parties shake up old politics

- Published

Spain's two party system is now a four-way fight between leaders Pablo Iglesias, Mariano Rajoy, Pedro Sanchez and Albert Rivera (L-R)

The emergence of two new parties has blown Spanish politics wide open.

The rise of the far-left Podemos party and centrist Citizens means the next general election, at the end of this year, is set to be a four-horse race.

For over three decades the Socialists (PSOE) , externaland centre-right Popular Party (PP), external have alternated in power, accounting for over 70% of the vote in past general elections.

But the impact of austerity policies and a focus on corruption has created unprecedented uncertainty.

And the "indignant" protest movement, which camped out in Madrid's central square in the summer of 2011, changed the nation's viewpoint on corruption.

The shift has been highlighted by an opinion poll, external that puts the one-year-old Podemos in the lead on 22.5%, the Socialists second with 20.2%, the PP third on 18.6% and Citizens, or Cs as the party has branded itself, with 18.4%.

Demonstrators camped out in Madrid in 2011, protesting at high unemployment rates and economic policies

A former PP treasurer revealed wholesale illegal financing of his party while the Socialist regional government in Andalusia oversaw a fraud totalling hundreds of millions of euros diverted from funds meant to help the unemployed.

Both are now stuck with the label of "la casta" (the caste), a term coined to great effect by Podemos.

Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias could be Spain's next prime minister, according to the polls

Podemos, external is the brainchild of a group of leftist political science university lecturers, headed by gifted orator Pablo Iglesias.

Only four months after they were founded, they attracted 8% share of the vote in last May's European elections.

'Going it alone'

Podemos argues Spain's crisis was a swindle on the part of the country's financial and political elite and vows to renegotiate its debt to its creditors in the same way as Greece's radical Syriza government is doing.

The Popular Party has faced public anger over corruption allegations linked to ex-treasurer Luis Barcenas (C)

Under Podemos, evictions of homeowners would be halted and welfare guaranteed for families hit by Spain's 24% unemployment rate.

"We didn't set up Podemos to become like the PSOE or PP - historical parties for our children and grandchildren to join as heirs of the founders," says the party's chief political analyst, Carolina Bescansa, a university lecturer.

"Our idea was to create a tool to allow people to join a participative process."

Podemos plans to open up government and submit major governmental decisions to referendums.

Thousands of Podemos supporters took to the streets of Madrid in January

'Sensible change'

Citizens, external has existed in the Catalan parliament since 2006 under the leadership of Albert Rivera, a lawyer who came to prominence through his stand against Catalan nationalism.

Last year he was engaged in talks with UPyD, a Spanish centrist party, which shares Citizens' desire to limit the autonomous powers of Spain's regions.

When negotiations broke down on electoral co-operation with UPyD, Cs decided to go it alone on the national scene and is now selecting candidates for a spate of regional and local elections taking place before the end-of-year parliamentary poll.

Podemos and Cs both insist on primaries to select electoral candidates and share the diagnosis of a Spain mired in corruption and economic ruin.

But they offer different cures.

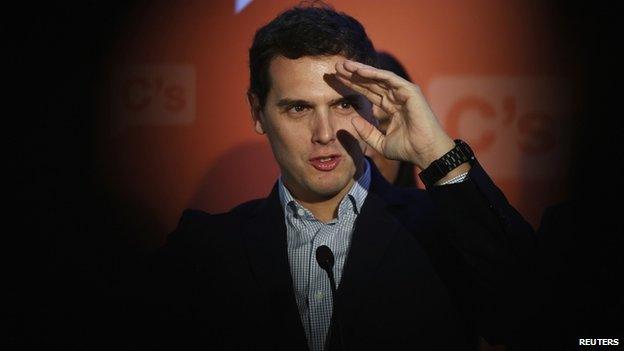

Albert Rivera came to prominence with his stance against Catalan nationalism

Podemos seeks to boost internal demand by raising income levels in poorer homes. Cs wants to reduce wasteful government layers, encourage investment and boost education.

"We need change and we need transparency, but it has to be sensible change," says Citizens' economic coordinator Luis Garicano, a professor at the London School of Economics, external.

"We are saying to Spaniards that we don't have to go the way of Venezuela or Greece. We can build another country, we can be the Denmark of southern Europe."

Mr Garicano says Podemos offers "handouts" while Cs wants to use well regulated markets to end "crony capitalism" and boost productivity.

Miguel de la Fuente, an unemployed 38-year-old from Gijon, says corruption and the precarious employment conditions afflicting his generation means he will be voting for Cs.

"I really believe they intend to bring about change. They want to boost the economy by allowing private companies to flourish and changing the education system," he said.

Desperation

Gracia Escalante, a 43-year-old social worker in Madrid has never voted before. But she wants to see Podemos get a chance to rule.

"I am angry that the basic pillars of welfare are being destroyed. I want a different kind of government," she added.

The two traditional parties of power are trying desperately to turn things around.

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy is using slightly improved financial circumstances to introduce tax breaks and pushing policies designed to help some of the country's indebted families.

For his part, Socialist leader Pedro Sanchez promises constitutional reform to set up welfare guarantees and a super tax for the rich.

But Jose Ignacio Torreblanca, head of the Madrid office of the European Council on Foreign Relations, external, argues the big two have lost their hold on much of the electorate.

"There is a perception that they are the same, that there is a convergence in their programmes. They have lost the capacity to redistribute positions of power and social benefits. They are seen as increasingly corrupt."

If Spain is on the cusp of a new political order, the first evidence will come in Andalusia, where the Socialists hope to cling on to their last major regional fiefdom in elections on 22 March.

- Published21 August 2023

- Published26 May 2014

- Published26 May 2014

- Published3 May 2014