Armenian tragedy still raw in Turkey 100 years on

- Published

Sevag Balikci's family say his death was connected to the anniversary of the massacre

Sevag Balikci never got to see his new bedroom.

His family, ethnic Armenians from Turkey, moved into their Istanbul apartment at the start of 2011.

Sevag was finishing his military service in the south-east. On 24 April, aged 25, he was shot dead by a fellow recruit.

The judge called it an accident, sentencing the killer to four years in prison. The family is convinced it was an intentional act by a Turkish nationalist, timed for maximum effect.

The 24th April is the date on which Armenians commemorate the darkest moment in their history: when - 100 years ago this week - they began to be rounded up in a crumbling Ottoman Empire and were deported or killed.

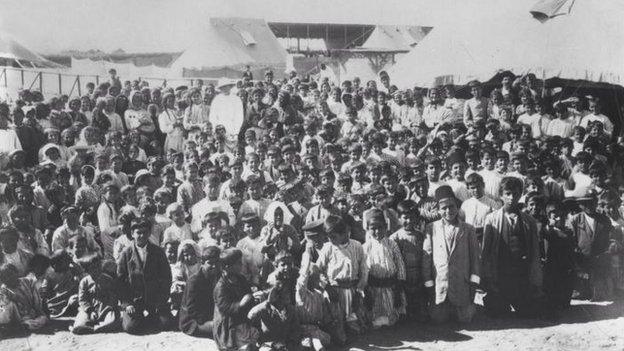

Armenian children at a refugee camp in 1915

Armenia says 1.5 million were systematically murdered, calling it "genocide".

Turkey fiercely rejects the label, insisting far fewer died - many of starvation or disease - and that the deaths of Turks have been ignored.

'The same fate'

As the centenary of the tragedy approaches, historical narratives are colliding.

"The genocide was being commemorated and the killer wanted to intimidate people through my son," says Ani Balikci, Sevag's mother.

"An Armenian had to die on that day - and Sevag was available.

"The authorities have leant on witnesses to change statements - it suits them to say it's an accident."

Sevag Balikci's grave lies at the heart of Istanbul's Armenian cemetery

She shows me her son's room, which she has kept as it was.

"We can't throw out his belongings because it would be like saying goodbye to him," she says, her tears flowing.

"A century ago, my family were killed in the genocide - and now one of their descendants, my son, has met the same fate."

Hushed up

Armenians had long been treated as second-class citizens in the Ottoman Empire, their sporadic revolts ruthlessly suppressed.

As World War One raged, Ottoman leaders blamed faltering national cohesion for losses in the Balkans and elsewhere, seeing the Armenian minority as a threat.

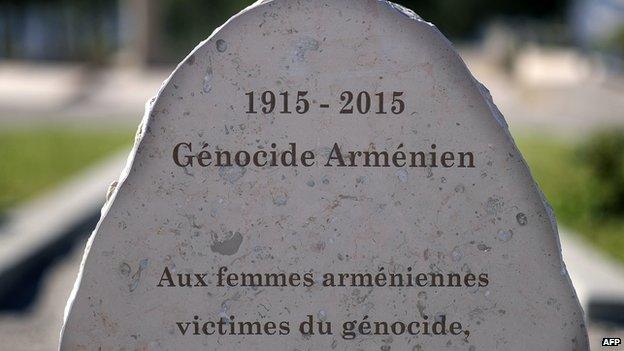

Armenian genocide dispute

Hundreds of thousands of Armenians died in 1915 at the hands of the Ottoman Turks, whose empire was disintegrating

Many of the victims were civilians deported to barren desert regions where they died of starvation and thirst. Thousands also died in massacres

Armenia says up to 1.5 million people were killed. Turkey says the number of deaths was much smaller

Most non-Turkish scholars of the events regard them as genocide - as do more than 20 states including France, Germany and Russia, and some international bodies such as the European Parliament

Turkey rejects the term 'genocide', maintaining that many of the dead were killed in clashes during World War One, and that many ethnic Turks also suffered in the conflict

From a pre-war Armenian population of two million, just 50,000 remain in Turkey today.

Around 20 countries, including France, Italy and Canada, officially recognise the killings as genocide.

But for decades Turks grew up unaware of what happened in 1915.

Textbooks omitted it; political leaders hushed it up, pursuing the "Turkification" of society.

When it was finally talked about here, the official Turkish version called it "the Armenian events".

But in the past decade, history classes at some universities have begun to address the period and a small liberal fringe has spoken out.

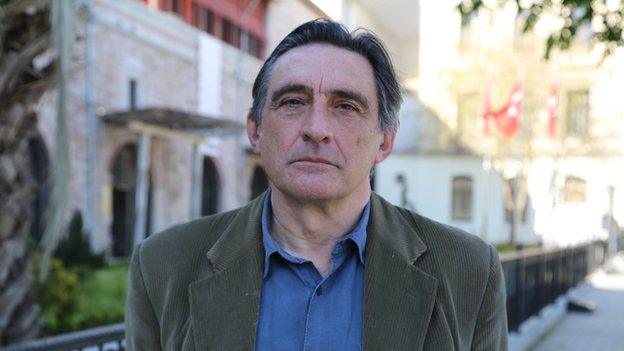

Professor Ahmet Insel says Turkey has a moral obligation to recognise the tragedy as "genocide"

Three hundred Turkish intellectuals signed a petition asking Armenia for forgiveness, among them Ahmet Insel, a professor at Galatasaray University.

"This was a genocide and a crime against humanity," he says, standing outside the Islamic Arts museum in Istanbul, the site where the first Armenians were rounded up.

"Turkey has a moral obligation to recognise it as such, so as to become a civilised modern democracy."

He says he does not expect formal recognition within the next 10 years.

"The charge of genocide could mean Armenians claim financial compensation from Turkey - that's one factor holding it back."

Rhetoric hardened

The current government has slowly moved forward on the issue, returning some confiscated properties to Armenians.

And, last year, the then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan - now President - offered his "condolences" to families of the victims, calling the killings "inhumane".

It was the furthest a political leader had gone in Turkey, but was rejected by Armenia for dodging the word "genocide".

In the run-up to the centenary, the rhetoric has again hardened.

The president is keen to maintain support among nationalists ahead of the election

When Pope Francis said two weeks ago that Armenians had suffered "the first genocide of the 20th Century" Mr Erdogan hit back, saying he "condemned" the Pope, warning him not to "repeat the mistake".

Partly the president is shoring up core nationalist votes ahead of an election in June. But partly too, Turkey, which cares so much for its prestige and strongman image, recoils at a word linked with Rwanda, Srebrenica and Auschwitz.

'Distract attention'

Perhaps no clearer example of the reluctance to mark the killings will come on the anniversary itself, when Turkey will instead lavishly commemorate 100 years since the Gallipoli campaign: the victory of Ottoman forces over invading Allied troops.

It is never remembered on 24 April but this year the ceremony will fall on that day - critics say to overshadow the Armenian anniversary.

President Erdogan invited world leaders to Gallipoli, including Armenia's president, who sent an angry rejection, calling it "an attempt to distract attention".

Most leaders have declined the invitation.

Hakan Aslan, of the far-right MHP party, insists Turkey's history is something to be proud of

On the shores of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, the far-right MHP party is campaigning for the election, repeating its unrepentant line on Armenia.

"There was no genocide," says Hakan Aslan, the party's regional head.

"All the ethnic groups who paid their taxes to the Ottoman Empire and weren't traitors lived in peace."

None of the graves at Istanbul's Armenian cemetery dates from 1915

Meanwhile at the heart of Istanbul's Armenian cemetery lies the grave of Sevag Balikci. A marble slab bears his name, picture and the date: 24 April 2011.

But among the surrounding graves, not a single one dates from 1915.

In fact, there is no cemetery in Turkey dedicated to those victims, such is the refusal to mark what happened.

A sign, say Turkey's critics, of a country still unable to face its past.

- Published21 April 2015

- Published12 April 2015

- Published23 April 2014

- Published24 April 2021

- Published30 January 2024

- Published14 December 2022