Spain's Rato corruption inquiry another blow for Rajoy

- Published

The Rato case is the latest in a string of corruption scandals to hit the Popular Party

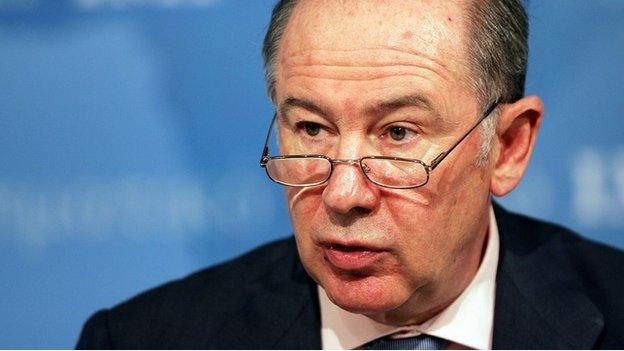

It was a sight most Spaniards never imagined they would ever see: former economy minister and IMF chief Rodrigo Rato gingerly stepping into a police car following his arrest as part of a money laundering and tax fraud investigation.

His detention, on 16 April, was brief and he was released only seven hours later.

But not before his home and office in Madrid had been searched by investigators as a crowd of TV cameras looked on from the street.

Rodrigo Rato, 66, was economy minister and deputy prime minister in the Popular Party (PP) government of Jose Maria Aznar, from 1996 until 2004, when Spain saw a period of sustained economic growth.

From 2004 until 2007 he was managing director of the IMF.

Prime Minister Rajoy has conceded that the Rato case is a "heavy blow"

'Spinal column'

According to documents leaked to Spanish media, tax officials believe Rodrigo Rato has sought to hide from them a web of companies in his name and a fortune worth €26.6m (£19m; $29m), which he is accused of keeping in foreign bank accounts in order to avoid paying taxes.

The former minister denies the allegations.

"Rato represents the PP's spinal column," says his biographer Ramon Tijeras. "Until not long ago, everyone in the party loved him, but nobody wants to have anything to do with him now."

The PP's current leader and prime minister, Mariano Rajoy, has admitted the allegations are "a heavy blow" for him and the party.

But this is only the latest and most eye-catching of a barrage of corruption claims that have embroiled the party in recent years and left it struggling as it faces some key elections.

Rodrigo Rato had already been forced to resign from the PP last year, in the wake of investigations related to his role as former CEO of lender Bankia.

The continuing inquiries include several allegations, all of which Mr Rato also denies:

That he lied about the bank's accounts before its disastrous stock exchange listing in 2011

That he oversaw the distribution of unsupervised bank credit cards to Bankia executives

That they used the credit cards to spend over €15m on everything from shoes and alcohol to African safaris

Campaigners wearing Rato masks have protested at alleged spending by Bankia managers

Public trust

Mr Rato's woes follow an ongoing investigation into allegations that the PP had, for many years, an illegal fund financed by corporate bribes that was used to make cash payments to senior members of the party, including Mariano Rajoy.

The prime minister has denied the claims and the case is still being investigated.

Meanwhile, PP politicians have been implicated in a network of bribery, tax evasion and money laundering in Madrid and Valencia, in a case which has been being investigated since 2009.

But other parties have also been tainted.

The opposition Socialists have been caught up in a major corruption case in Andalucia, and the Catalan nationalists of Convergence and Union (CiU), have been embroiled in a tax evasion scandal.

Podemos, led by Pablo Iglesias (C), stands to benefit from public anger at corruption

Corruption is one of the main reasons why Spaniards' faith in many of their major institutions - from parliament and banks to the justice system and royal family - has been eroded in recent years.

"It's always been like this, but in the old days we never used to find out about it," said Maria Dolores Barbero, a pensioner, as she left a branch of Bankia in central Madrid.

This disenchantment with the traditional powers helps explain the sudden rise of two new political forces in recent months: Podemos on the left and Citizens (Ciudadanos in Spanish) on the right.

Both have prioritised the battle against corruption and polls have them in a virtual four-way tie with the PP and Socialists ahead of regional and municipal elections to be held on 24 May.

A general election is expected by the end of the year.

Fernando Vallespin, a political scientist at Madrid's Autonoma University, believes the recent glut of corruption cases, combined with the approaching elections, mark the end of a cycle.

"Before, there was the idea that 'I'll keep voting for the PP because the Socialists also have their scandals'," he said.

But now Spanish voters are offered an alternative to the political mainstream that many see as tainted.

- Published16 April 2015

- Published14 March 2015

- Published1 August 2013