Austrian city faces hidden horrors of Nazi camp

- Published

A military court set up by the British sentenced two men to death in 1947 over the atrocities in Liebenau

For almost seven decades it has been a largely forgotten chapter in a painful past.

But now Austria's second largest city is coming to terms with the deaths of dozens of Nazi prisoners - many of them Hungarian Jews - within its walls.

Graz hosted a conference on the history of the Liebenau labour camp on Tuesday amid attempts to bring horrors committed 70 years ago to light.

It focused on the events of April 1945, in the final weeks of World War Two.

It was during this time that a group Hungarian Jews were held briefly at a Nazi labour camp in Liebenau - in a southern district of Graz - as they were led on a death march to Mauthausen concentration camp in northern Austria.

Many of them were severely weakened, starved and sick.

When they arrived at the Liebenau camp, which was otherwise used to hold prisoners of war and foreign slave labourers, they were denied food and medication, and were forced to sleep outside despite the cold.

During those weeks at least 35 member of the group were shot dead. Their identities - and the location of many of the bodies - remain largely unknown.

Shocked

"The aim of the conference is to open the whole topic to the public so it becomes better known here," said Barbara Stelzl-Marx, vice president of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Research on War Consequences in Graz.

"This is not something that has been well known, or part of the collective memory."

Victims of the Mauthausen concentration camp seen in 1945

Today the site of the Liebenau camp is less than a mile from the UPC Arena, Liebenau's football stadium.

The deaths of the prisoners only re-emerged as part of Ms Stelzl-Marx's research into forced labour camps in 1998.

It is believed they may have been killed because they were no longer able to march, or as a warning to others.

"I have lived in Graz most of my life so I was really shocked by this information," Ms Stelzl-Marx told the BBC.

"This happened on our doorstep."

But it was only when plans for a hydro-electric power plant on the River Mur, which flows next to the site, were submitted more recently that interest really grew.

People asked whether the development could disturb the burial places of the victims.

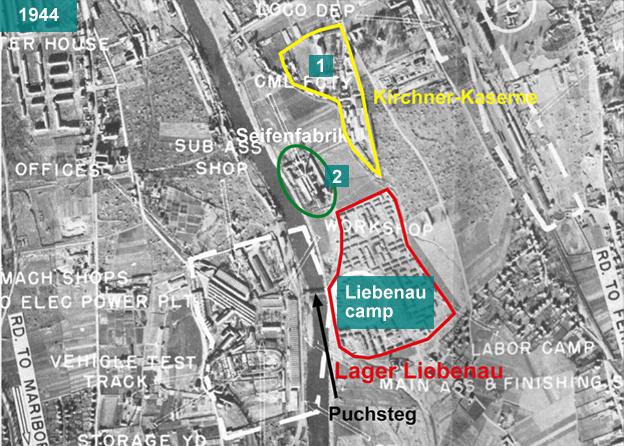

A US map of Liebenau camp from 1944 shows the Liebenau camp close to barracks (1) on the banks of the River Mur and a soap factory (2)

The remains of one building can still be seen just south of the soap factory (2) and near the stadium

'Wall of silence'

Ms Stelzl-Marx says most of the bodies were thought to have been exhumed by British forces in 1947, although one newspaper source at the time suggested not all of them had been moved.

A military court set up by the British convicted four camp guards the same year, two of whom were sentenced to death.

But after this, a "wall of silence" came down, Ms Stelzl-Marx says.

"Grass grew over the whole story."

Modern architecture mixes with old on the banks of the River Mur in present day Graz

The Allies handed the process of dealing with the aftermath of WWII to the Austrian government after 1947.

Prof Helmut Konrad of the University of Graz describes what happened next as a "story of shame".

He said Austrians refused to accept their country's involvement in Nazi crimes, instead insisting they were the "first victims".

"No-one cared to talk about this topic," Prof Konrad told the BBC.

Even when he arrived in Graz in the 1980s, he had "no idea" about the Liebenau camp, he says.

Memorial

The remains of just one of the camp's buildings are visible in the city; they are believed to have been the complex's kitchen.

Ms Stelzl-Marx says she cannot say for sure whether or not bodies of the victims remain in the ground in Graz.

But the city's mayor announced on Tuesday that a memorial would be erected in their honour.

It is part of broader efforts Austria is making to address its difficult history, including pushing for looted objects and artworks to be returned to their rightful owners.

Prof Konrad says this has created a "clearer picture" of the country's involvement.

"The picture has taken a very long time," he says.

"But Austria is no longer behind other countries in terms of recognising collective participation in Nazi crimes."

- Published29 December 2014

- Published11 February 2014

- Published6 March 2015