Will EU Commission's quota plan for migrants work?

- Published

Migrants fleeing unrest in Libya risk their lives aboard unseaworthy boats in the Mediterranean

The European Commission has unveiled new proposals for dealing with Europe's migration crisis.

The Commission has called for mandatory national quotas to relocate many migrants who have reached Europe. That is highly controversial, and there will be intense government discussions about the proposal.

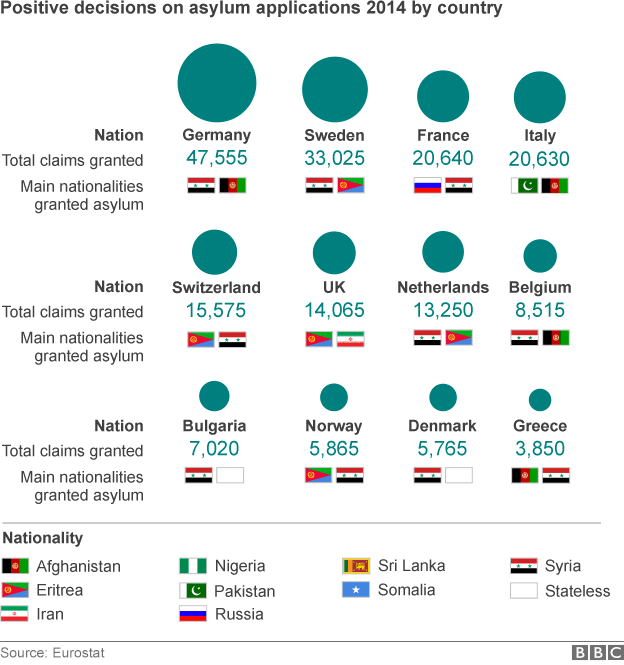

Countries in the front line of the migration surge want a fairer EU-wide distribution of the burden. Italy faces unprecedented migrant boatloads in the Mediterranean, while Germany faces by far the most asylum claims.

What is the Commission asking member states to do?

The Commission has issued the "European Agenda on Migration", external, setting out common policy goals for the 28-nation EU to adopt and make law.

It argues that the current system is failing to cope with the migrant influx, which is fuelled by the profits made by people traffickers. The war raging in Libya has exacerbated the flow from there.

There is a human rights imperative for the EU too, as the Mediterranean has seen more than 1,800 migrant deaths at sea this year. Migrants who make it to Europe are often deeply traumatised by the traffickers' brutality.

The impulse for this far-reaching agenda came from the escalating crisis in the Mediterranean and a 10-point emergency plan, external from EU governments. It called for "a systematic effort to capture and destroy vessels used by the smugglers". It also said the EU must "consider options for an emergency relocation mechanism" for migrants.

Mediterranean migration in numbers

The Commission has come up with a "distribution key" to spread the burden of processing asylum claims in the EU. Italy, Greece and Malta are struggling to cope.

That new mechanism is based on countries' population size, GDP, unemployment rate and numbers of existing asylum applications.

Separately, the EU aims to bring 20,000 refugees to Europe in the next two years, at a cost of €50m (£36m). That is being organised in non-EU countries with the UN refugee agency (UNHCR).

Under the Geneva Conventions, external, refugees fleeing from persecution or life-threatening violence have a right to claim asylum in Europe.

The Commission acknowledges that too many poor economic migrants have managed to remain in Europe. Co-operation must be tightened with the main countries of origin - many of them in Africa - to tackle that problem and send more migrants home, the Commission says.

So would the UK and other EU countries be forced to accept more migrants?

To become law the proposal for mandatory quotas has to be agreed by a majority of member states. That could be difficult and there is a long way to go.

The UK, Ireland and Denmark have opt-outs from parts of EU justice and home affairs (JHA) policy. As EU law professor Steve Peers explains in this blog piece, external, they can use those opt-outs to avoid any mandatory burden-sharing.

A legal difficulty for the UK might arise if the quota system affects the EU's Dublin Regulation, external. It states that asylum claims should be handled by the member state that played the greatest part in the applicant's entry or residence in the EU. Often that is the first EU country that the migrant reached - meaning that Greece, Italy and Malta are under particular pressure now.

The UK and some other EU countries use the regulation as a legal basis for deporting illegal migrants and failed asylum seekers. But a quota system might put a limit on such expulsions.

What is the reaction to the Commission plans?

Germany supports the proposed EU distribution key, because it would ease its own asylum burden. Nearly 250,000 people have applied for asylum in Germany in the past 12 months - far more than in any other EU country.

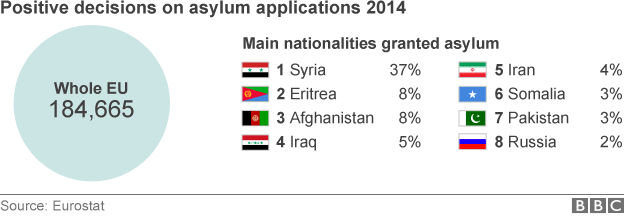

Last year 90% of asylum applications in the EU were lodged in only 10 member states. Sweden and Hungary also have high applicant totals relative to their population.

Italy and Austria are among those who favour a quota system. And French Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve also voiced support, saying "I think it's normal to share out the asylum claimants" among EU member states.

But Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban rejected what he called a "mad and unfair" proposal.

And a UK Home Office spokesman said "we will oppose any EU Commission proposals to introduce a non-voluntary quota".

The spokesman said the EU must focus on stopping "the vile trade in human beings". That means boosting co-operation between law enforcement agencies, stopping the transit of migrants in non-EU countries and "establishing a more effective process of returning illegal migrants".

For the incoming Conservative government under David Cameron immigration is a priority area for winning concessions from Brussels.

Why is it proving so hard to stop the influx of migrants?

What a Mediterranean rescue looks like

The Commission admits that the EU's current Common European Asylum System , externalhas "fallen short".

A combination of factors make this a particularly difficult issue for the EU:

Wars have escalated on the periphery of the EU, driving refugees towards Europe - Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and Libya are all engulfed in conflict

Developing countries are often chronically under-resourced to accommodate refugees

Often migrants arrive with few or no papers, so it is hard to filter genuine refugees from the many economic migrants

The mechanism for sending irregular migrants back is very patchy - in 2013 only 39% of migrant return decisions were enforced, and people traffickers exploit that weakness

Globalisation and the media revolution have fuelled migrants' expectations - many dream of starting a new life in Europe

The economic slump and nationalist backlash in Europe have made immigration a hot political topic, so low-skilled migrants are often unwelcome.