Why is EU struggling with migrants and asylum?

- Published

Migrants continue to accumulate on the Greece-Macedonia border

Europe is experiencing one of the most significant influxes of migrants and refugees in its history. Pushed by civil war and terror and pulled by the promise of a better life, huge numbers of people have fled the Middle East and Africa, risking their lives along the way.

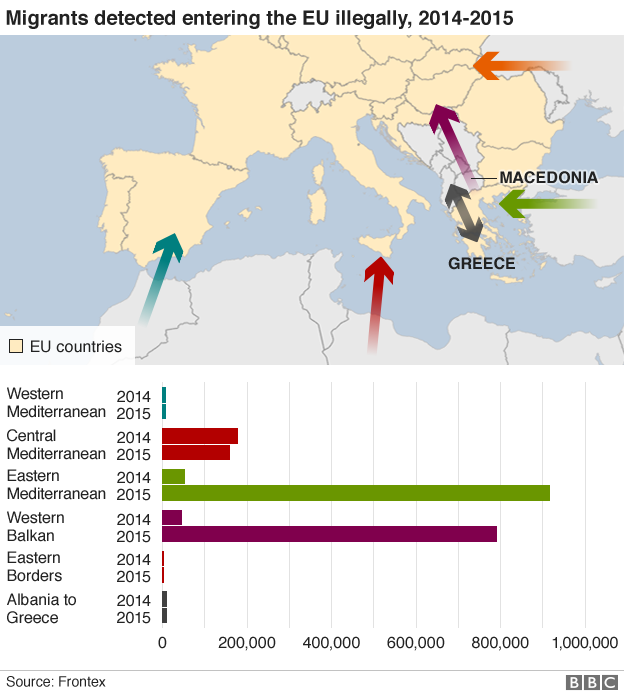

More than a million migrants and refugees crossed into Europe in 2015, compared with just 280,000 the year before. The scale of the crisis continues, with more than 135,000 people arriving in the first two months of 2016.

Among the forces driving people to make the dangerous journey are the conflicts in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. The vast majority - more than 80% - of those who reached Europe by boat in 2015 came from those three countries. , external

Poverty, human rights abuses and deteriorating security are also prompting people to set out from countries such as Eritrea, Pakistan, Morocco, Iran and Somalia in the hope of a new life in somewhere like Germany, Sweden or the UK.

But as European countries struggle with the mass movement of people, some have tightened border controls. This has left tens of thousands of migrants stranded in Greece, raising fears of a humanitarian crisis.

As leaders grasp for a solution, they have increasingly looked to Turkey, hoping to slow the number of people setting off for European shores.

What routes are people using?

The most direct routes are fraught with danger. In 2015 more than 3,770 people drowned or went missing crossing the Mediterranean to Greece or Italy in flimsy dinghies or unsafe fishing boats.

Most of those heading for Greece take the relatively short voyage from Turkey to the islands of Kos, Chios, Lesbos and Samos. There is very little infrastructure on these small Greek islands to cope with the thousands of people arriving, leaving overburdened authorities struggling to provide vital assistance.

Others migrants continue to travel by boat from Libya to Italy, a longer and more hazardous journey.

Some of the worse tragedies in 2015 included:

Two boats carrying about 500 migrants sank after leaving Zuwara in Libya on 27 August

The bodies of 71 people, believed to be Syrian migrants, were discovered in an abandoned lorry in Austria on 27 August

A shipwreck off Italy's Lampedusa island killed about 800 people on 19 April

At least 300 migrants are feared to have drowned after attempting to cross the Mediterranean in rough seas in early February

Survivors often report violence and abuse by people traffickers, who charge thousands of dollars per person for their services. The chaos in Libya in particular has given traffickers freedom to exploit migrants and refugees desperate to reach Europe.

Where are they going next?

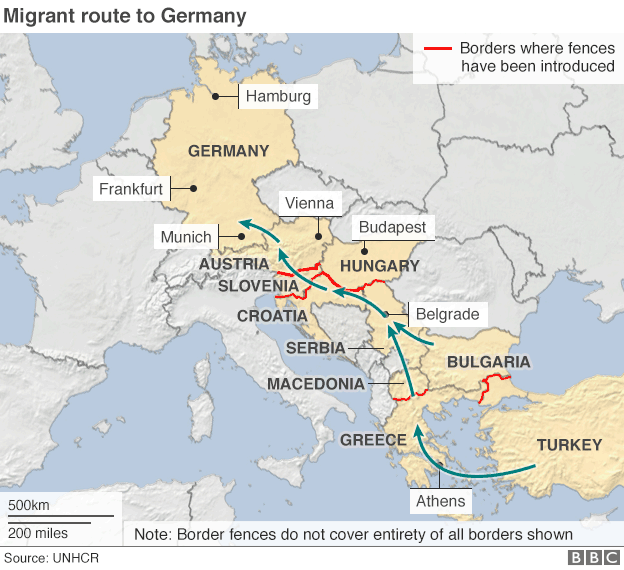

Many attempting to reach Germany and other northern EU countries go via the perilous Western Balkans route, running the gauntlet of brutal people traffickers and robbers.

Faced with a huge influx of people, Hungary was the first to try to block their route with a razor-wire fence. The 175km (110-mile) barrier was widely condemned when it went up along the Serbia border, but other countries such as Slovenia and Bulgaria have erected similar obstacles.

Austria has placed a cap on the number of people allowed into its borders. And several Balkan countries, including Macedonia, have also decided only to allow Syrian and Iraqi migrants across their frontiers.

As a result, thousands of migrants have been stranded in makeshift camps in cash-strapped Greece, which has asked the European Commission for nearly €500m in humanitarian aid.

Under an EU rule known as the Dublin regulation, refugees are required to claim asylum in the member state in which they first arrive.

But some EU countries, such as Greece, Italy, and Croatia, have been allowing people to pass through - often via the passport-free Schengen zone - to countries further north. And those countries are often failing to send migrants back.

Germany received more than 1.1 million asylum seekers 2015 - by far the highest number in the EU.

Hundreds of thousands of people are somewhere along the route, in Hungary, Croatia, Austria, Serbia, and elsewhere.

Meanwhile between 2,000 and 5,000 migrants are camped at the French port of Calais in the hope of crossing over to the UK.

Are EU countries doing their fair share?

Germany has been critical of other EU countries - including France and the UK -over their relatively meagre commitments to take people in.

In September, EU interior ministers approved a controversial plan to relocate 120,000 migrants across the continent over the next two years, with binding quotas. Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary opposed the scheme.

Despite some efforts to ease the burden on Italy and Greece, only small groups of migrants have been relocated so far and several states in Central and Eastern Europe have refused to accept them.

The rules governing immigration to the EU - explained in 90 seconds

For years the EU has been struggling to harmonise asylum policy. That is difficult with 28 member states, each with their own police force and judiciary.

Championing the rights of poor migrants is difficult as the economic climate is still gloomy, many Europeans are unemployed and wary of foreign workers, and EU countries are divided over how to share the refugee burden.

More detailed joint rules have been brought in with the Common European Asylum System, external - but rules are one thing, putting them into practice EU-wide is another challenge.

EU leaders now hope Turkey can help to reduce the number of migrants arriving in EU nations. In February the bloc approved €3bn ($3.3bn; £2.2bn) in funding for the country to help it cope with record numbers of Syrian migrants it is already hosting.

European Council President Donald Tusk says it is up to Turkey to decide how to reduce the flow to Europe, but that it could be time to turn back migrant boats trying to reach Greece.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule are economic migrants.

- Published19 August 2015