Turkey election trip: Izmir looks West amid growing conservatism

- Published

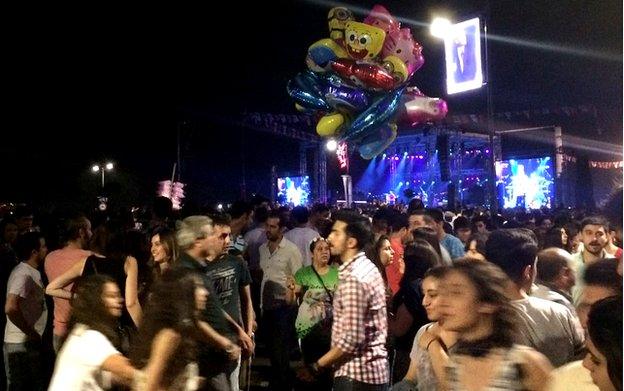

The guitar riff builds, the lyrics boom out - and Izmir's music-loving fans roar.

The alcohol is flowing, the skirts short: this is the epitome of Turkey's most liberal, Westernised city - and my first stop as I travel across the country ahead of Turkey's upcoming election.

"You have pepper spray, you have tear gas…but we're still free…this country is ours," the fans sing.

On the stage at Izmir's seafront is Duman, one of Turkey's best-loved rock bands. As they belt out tunes about the anti-government protests of 2013, the thousands-strong crowd goes wild.

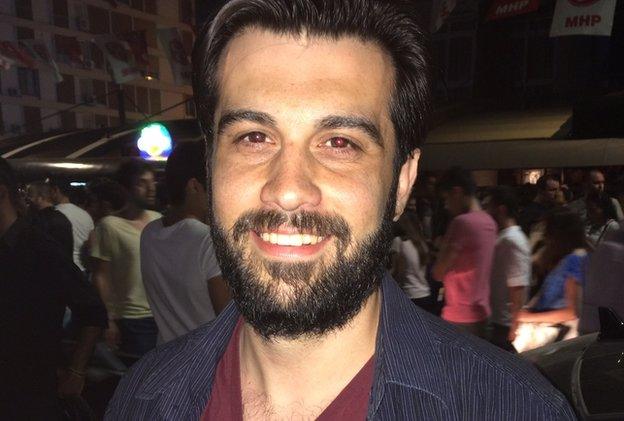

Serbay Kos says people outside Turkey wrongly see his country as conservative

"When I was studying in Poland, people there thought Turkey is a heavily Muslim country; that the women are all covered and men have four wives," laughs Serbay Kos, a volleyball trainer.

"But Izmir isn't like that - we're like Europe and America."

He takes a swig of beer as the song changes.

"I'm worried that this government is trying to make Turkey into a more Muslim country, like Iraq or Syria - but we want to be free."

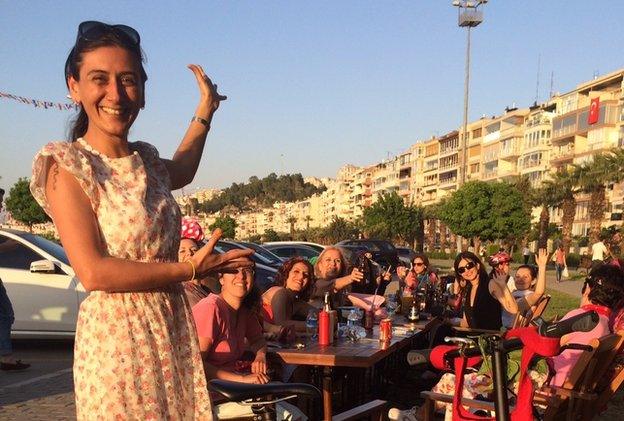

Mark Lowen joins an all-women's group of cyclists in Izmir

'Pious generation'

It is a sentiment you hear frequently in this relaxed, coastal city - Turkey's third largest.

Izmir has always looked across the Aegean to Europe; its Greek heritage and affluent bon-viveur feel shaping its politics.

Izmir is the first stop on Mark's tour around Turkey ahead of the election. Follow the journey #bbcturkey15

The centre-left Republican People's Party, or CHP, has its stronghold here - Izmir is known as the "CHP's castle".

Staunchly secular, it is the party of modern Turkey's founding father, Kemal Ataturk.

In the last election, the CHP took 44% of the vote in Izmir - more than double its national share. And it is aiming higher for the poll on 7 June.

Many here fear the growing conservatism of the current government.

Under the 12-year rule of the Islamist-rooted AK Party, constitutionally-secular Turkey has fundamentally changed.

There is now a push to raise a "pious generation" - in the words of Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan - and CHP-dominated Izmir appears increasingly isolated.

CHP candidate Zeynep Altiok says her party wants to bring people freedom

But in the Bostanli market of Izmir, local CHP candidate Zeynep Altiok is full of confidence.

We stroll through the rows of artichokes, succulent tomatoes and oranges.

These are rich pickings for the customers - and for campaigning politicians, as she secures vital votes.

"Turkey is a big mosaic," Ms Altiok tells me, as she is handed a slice of melon by one supporter.

"There should be no extremes. Neighbours live beside each other, one wearing a headscarf, one without - that's what we must do.

"But the government labels you: you're either with them or against them. We have to break this."

Women's rights

Warm words, but the CHP's history isn't exactly inclusive. For decades it embodied old-school nationalism, taking a hard line towards Turkey's minorities, especially the Kurds.

And it is still seen by critics as the party of the so-called "white Turks", the wealthier, Westernised parts of society.

But Ms Altiok insists the party has changed.

"It's now totally modern. We don't discriminate. Our approach is to bring freedom for everybody in this country."

At the top of its agenda is the issue of women's rights.

The government has constantly stressed its vision of stay-at-home mothers, urging three children per family. Last year, the deputy prime minister told women not to laugh in public; the president recently insisted that men and women were "not made equal".

These female cyclists are challenging traditional images of women in Turkey

'Not democracy any more'

On the corniche in Izmir, female defiance is clear.

Hundreds have joined an all-women cycling group to promote empowerment as well as concern for the environment.

Some wear short, brightly-coloured dresses, others have flowers in their hair.

"The Turkey I want has respect for all citizens - men and women - giving everyone the same opportunities," says Pinar Pinzuti, pedalling along the bay as the afternoon sun glints on the water.

"Turkey needs to change: we need a country with allies, with respect for opposite opinions - and with democracy. This is not democracy any more."

Izmir's resistance to the growing advance of religion here is closely tied to its history.

It was the city most associated with Turkey's war of independence from 1919, where Ataturk's army rose up against the Allied troops.

And it was the place that sealed Turkey's victory in 1922 when the Turkish army recaptured the city.

Cycling group member Pinar Pinzuti wants women and men in Turkey to have the same opportunities

Hundreds of thousands of Greeks and Armenians were killed or driven out, a fire engulfing their parts of the city.

While Greece still mourns its loss, Turkey sees it as a nationalist triumph.

And so reverence for Ataturk - and his free, secular Turkish identity - is at its height here.

Kemal Ataturk

Kemal Ataturk (centre) is seen in Izmir, Turkey, after the modern Turkish Republic was founded in 1923

Founder of the Turkish republic

Born in 1881

President from 1923

Died in 1938

'Religion non-stop'

His picture adorns buildings, and crowds visit the house where he married his wife, Latife.

"Ataturk means the world to me", says 15-year-old Lara Agon, visiting the house on a school trip.

"He worked all his life to separate religion from politics - and he would be upset that today our government is holding Korans in rallies and talking about religion non-stop."

As their tour comes to an end, younger children from the next-door school gather outside for a weekly ceremony. The Turkish flag is raised, the national anthem is sung and they stand for a minute's silence.

Selin Girit visits a school in Izmir, one of Turkey's most secular cities

This is a deeply proud city - but one that feels the "Turkishness" for which it fought has been hijacked; transformed into a conservative, Middle Eastern identity that people do not recognise.

This large and multifaceted country has always grappled with its diversity, and politicians have struggled to appeal to all sides.

That split is likely to be accentuated in next month's election as Turkey's political polarisation deepens.

Follow the BBC News journey around Turkey ahead of the election using the hashtag #bbcturkey15, external.

- Published24 November 2014

- Published22 August 2023

- Published4 March 2015

- Published16 April 2015

- Published27 November 2014