Gay marriage Yes vote shows how much Republic of Ireland has changed

- Published

There were emotional scenes as referendum votes were counted in Dublin

The BBC's Shane Harrison looks at how the Republic of Ireland's vote in favour of legalising same-sex marriage caps an extraordinary week for the country.

The Republic has become the first country in the world to introduce same-sex marriage in a popular vote, just days after the Prince of Wales visited Mullaghmore in County Sligo where his great-uncle Lord Mountbatten was murdered by the IRA in 1979.

While in Sligo, Prince Charles also visited the grave of the Irish poet, WB Yeats, under the shadow of Ben Bulben mountain in Drumcliffe cemetery.

The poet was born 150 years ago and many of his verses were quoted during the Royal visit.

The Prince of Wales visited the grave of WB Yeats during his visit to County Sligo

Nearly every Irish student learns the lines from the poem September 1913: "Romantic Ireland is dead and gone, it's with O'Leary in the grave."

O'Leary was an old Irish revolutionary who wanted to free Ireland from British rule.

The referendum result speaks volumes about a changed Republic of Ireland and it is tempting to write: "Catholic Ireland is dead and gone."

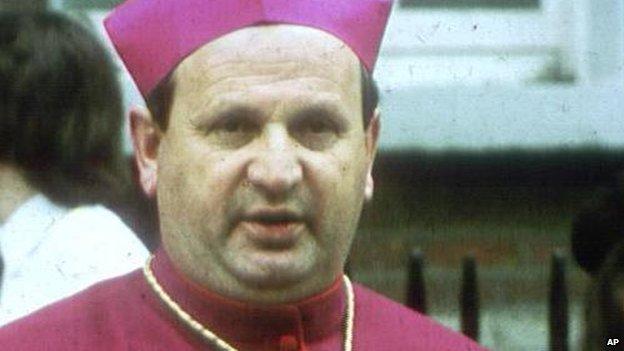

It was the revelation that Bishop Eamon Casey had fathered a child that first started a process which, for many, undermined the authority of the Catholic Church.

Bishop Eamon Casey had a son with American woman Annie Murphy

Soon afterwards a tsunami of revelations about child sex abuse involving priests and cover-ups by bishops further and greatly diminished the standing of the church hierarchy in a country that is nominally 85% Catholic, although empty churches and declining Mass attendance tell another story.

It was only in 1993 that homosexual acts were decriminalised; civil partnership was introduced in 2010.

Throughout the campaign, bishops preached against a "Yes" vote for same-sex marriage and indicated their deep unhappiness with the government's proposal.

They were joined by social conservatives and Catholic lay groups in expressing their view that the proposal undermined the traditional family of a husband, a wife and children.

A snapshot of gay rights around the globe

But only three of the 166 members of the Irish parliament publicly supported that view and urged a "No" vote.

Against the hierarchy stood a coalition of all the main political parties, gay rights activists and their families and supporters.

It is noticeable that the "Yes" vote was strongest in more urban areas and among younger voters who study the African-American struggle for civil rights for their state exams.

And it was also noticeable in conversations how many of them were influenced by that struggle for equality in Saturday's result.

Thousands returned from abroad to vote, and thousands more delayed their working holidays after finishing university exams to register their support for the government's proposal.

Social media was abuzz with their stories.

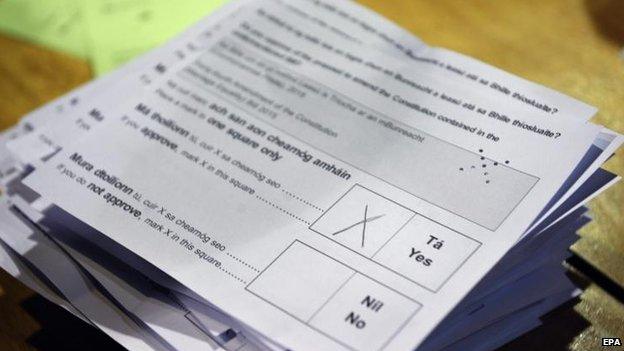

Voters were asked if they agreed with the statement: "Marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex"

Some "No" campaigners feared the worst from early on; some privately said that even if they won this time they knew they were battling against the tide of history because such was the strength of feeling among young people that there would be another referendum and it would then pass.

Today, though, is not the first recent indication of the diminished standing of the Catholic Church.

Two years ago, the bishops failed to stop the government and politicians from introducing legislation to allow for abortions in cases where there was a credible suicide threat from a woman if she was forced to continue with her pregnancy.

And in many ways the same-sex marriage referendum is just one stage in church-state relations before the main confrontation - the repeal of the eighth amendment to the constitution that gives an equal right to life to the mother and the unborn.

Oscar Wilde is perhaps the best known Irish gay man

The referendum on this in 1983 was extraordinarily divisive and left a bitter taste in the mouths of many involved.

While another referendum on repealing the amendment is unlikely until after the next election, both sides are already preparing for it.

Those wanting change argue that it currently prevents terminations in cases of fatal foetal abnormality, where the foetus cannot survive outside the womb, and where a pregnancy has resulted from rape or incest.

Those seeking the retention of the amendment - and it's not just the Catholic Church and other Christian institutions - argue from a human rights point of view that the foetus or unborn child also has a right to life.

But that's all for another day.

I began with WB Yeats but I'll finish with, perhaps, the best known Irish gay man, Oscar Wilde.

The phrase "the love that dare not speak its name" comes from a poem by his lover Lord Alfred Douglas and was mentioned at Wilde's gross indecency trial that would see him jailed.

After the same-sex referendum result, not any longer, Oscar, not any longer.