Greek stand-off could slide out of control

- Published

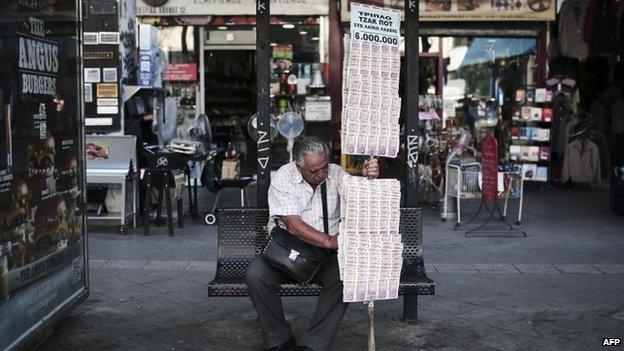

Greek lottery: one way to beat austerity in Athens

After four months of brinkmanship, Greece faces days full of risk. A deadline approaches.

On Friday, Athens is due to make a repayment of 300m euros (£218m) to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The date may slip, but Greece has to make four payments in June, reaching a total of 1.6bn euros.

If it fails to deliver, it will be in default.

In the meantime, the game continues.

Europe's leaders have drawn up what is being called a take-it-or-leave-it offer.

Athens has pre-empted this with a 47-page proposal of its own.

The Greek government needs an agreement to unlock the remaining bailout funds and so remain solvent.

The international community watches warily.

Jason Furman, the chairman of the White House's Council of Economic Advisers, said: "Greece remains a potential accident."

The Greek Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has returned to Brussels insisting it is now up to Europe to "adjust to realism".

Some of his ministers back home breathe defiance.

"If there is no prospect of a deal by Friday or Monday," said Nikos Filis, "we will not pay."

Gathering momentum

In all these twists and turns, the greatest risk for Greece and the eurozone is that events take on a momentum of their own.

In April, savers withdrew nearly 5bn euros. Bank deposits have fallen sharply.

Alexis Tsipras faces tough negotiations

The frequently delivered optimistic notes coming out of Athens are partly aimed at reassuring nervous depositors.

But what if pensioners or public-sector workers began to fear they would not be paid or if there were signs of a bank run?

Capital controls would follow, and both Europe's leaders and Athens would struggle to retain control of events.

On the most basic issue, there is agreement. A majority of Greeks want to stay in the eurozone.

So does Alexis Tsipras and most of his Syriza coalition.

The rest of the EU wants Greece to stay in the eurozone.

The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, has staked a lot in supporting Greece when others were prepared to contemplate the country leaving the euro.

Why then has it proved so hard to strike a deal?

Eurozone democracy

The crisis is in part an argument over the meaning of democracy in the EU and the eurozone.

Greece was bailed out twice. It got 240bn euros, but austerity, which was a condition of the loans, was widely judged to have failed.

The economy shrunk by 25% in six years, an unprecedented decline for a modern economy.

Nobody doubted that Greece needed reforming, but the question was whether the medicine was killing the patient.

That sense that Greece was a laboratory for a German-designed austerity plan propelled Mr Tsipras's radical left party to victory in January.

I was at a rally where he boldly declared that the day after the election would see the start of the end of austerity.

It was a promise that could not be kept, because Greece belongs to a monetary union that sets rules.

The new Greek government insisted it had a mandate to move away from austerity, but many of Europe's leaders did not see it that way.

The German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schaeuble, said: "Elections change nothing."

President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker said: "There can be no democratic choice against the European treaties. One cannot exit the euro without leaving the EU."

Mr Schaeuble now says that Syrizia misled voters by promising they could stay in the euro without having to submit to major and painful reforms.

"Perhaps they shouldn't have made election promises like this," he said.

Learning lessons

In the past four months, Mr Tsipras has been learning there is a different kind of democracy within a monetary union.

The wishes of the Greek voters have to be balanced with the views of voters in other eurozone countries.

The other countries in the eurozone were determined not to allow a popular vote to challenge and undermine the management of the single currency.

Sigmar Gabriel has warned of "gigantic" fallout from Greek bankruptcy

They insisted that Greece had to stand by commitments made by the previous Greek government.

They feared that if they showed weakness, it would only encourage other anti-austerity parties to agitate against the rules.

Mr Tsipras came to the conclusion that the EU powers wished "to make an example of Greece".

He is hemmed in by the promises made to his voters and some in his party who will fight any further reforms.

The eurozone, on the other hand, is hemmed in by the mood in its various parliaments, which would have to approve any deal.

There is increasing resistance to helping Greece further without verifiable commitments to fundamental reform.

The sticking points remain:

pension reform

changes to the labour market

VAT rates

the size of the budget surplus

If Mr Tsipras was to make significant concessions on pension reform, he would face significant opposition from within his own party.

Greece in numbers

€320bn

Greece's debt mountain

€240bn

European bailout

-

177% country's debt-to-GDP ratio

-

25% fall in GDP since 2010

-

26% Greek unemployment rate

The Greek Government argues that if the eurozone insists on a budget surplus above 1%, then it will only further weaken demand in the economy.

If Angela Merkel, Francois Hollande and the other European leaders push too hard, then Alexis Tsipras might prefer to go for fresh elections or even to hold a referendum, but in the meantime there would be a risk of the country defaulting.

Back in 2013, the fear was of contagion - that if Greece left the euro, other countries might follow.

Most of those fears have subsided. Officials believe they could manage a Greek exit.

Even so, the fallout from a Greek bankruptcy would be in the words of Sigmar Gabriel, the German Vice-Chancellor, "gigantic".

Which is why a last-minute compromise deal is still the most likely outcome.

Even if that is achieved, the Greek crisis does not go away. A deal only buys a few months.

The country has debts of 320bn euros. Most of that money is owed to EU governments. Greece's debt-to-GDP (gross domestic product) ratio is approaching 180%.

So if the immediate crisis wanes, there will be the question of whether Greece will need a third bailout - somewhere between 30bn and 50bn euros.

Getting that through the Bundestag, the lower house of the German parliament, will not be easy.

So the Greek saga is set to continue even if a typical Brussels compromise emerges at this, the eleventh hour.

But the risk is that Athens and Europe's leaders continue to misread each other and an accident happens.