Germany's oldest student, 102, gets PhD denied by Nazis

- Published

The dean of the university's medical faculty said Ms Rapoport had been "brilliant" in her exam

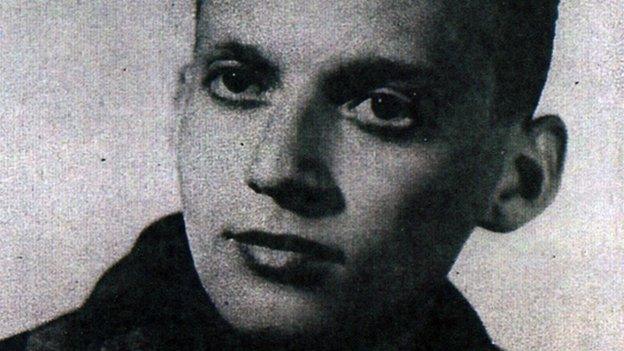

A 102-year-old German woman has become the world's oldest person to be awarded a doctorate on Tuesday, almost 80 years after the Nazis prevented her from sitting her final exam.

Ingeborg Rapoport (then Syllm) finished her medical studies in 1937 and wrote her doctoral thesis on diphtheria - a serious problem in Germany at the time.

But because of Nazi oppression she has had to wait almost eight decades before being awarded her PhD.

Her mother was a Jewish pianist.

So, under Adolf Hitler's anti-Semitic race laws, Ingeborg was refused entry to the final oral exam. She had written confirmation from Hamburg University that she would have received her doctorate "if the applicable laws did not prohibit Ms Syllm's admission to the doctoral exam due to her ancestry".

'For the victims'

Now the university has set right that wrong.

Three professors from Hamburg University's medical faculty travelled last month to Ingeborg's sitting room in east Berlin to test her on the work she carried out in pre-war Germany.

Ingeborg Rapoport said she was very nervous as she was examined by Hamburg University academics

They were impressed and a special ceremony took place at Hamburg University Medical Centre on Tuesday, in which she finally received the PhD that the Nazis stole from her.

"It was about the principle," she said. "I didn't want to defend my thesis for my own sake. After all, at the age of 102 all of this wasn't exactly easy for me. I did it for the victims [of the Nazis]."

To prepare for last month's exam, Ingeborg enlisted friends to help her research online what developments there had been in the field of diphtheria over the last 80 years.

"The university wanted to correct an injustice. They were very patient with me. And for that I'm grateful," she told Der Tagesspiegel newspaper.

A life in medicine

1912 - Born in Cameroon (Germany colony)

1938 - After studying medicine in Hamburg, prevented by Nazis from defending PhD thesis on diphtheria

1938 - Emigrates to US, meets Mitja Rapoport

1952 - Moves to East Berlin with family

1958 - Qualifies as paediatrician, becoming professor in 1964

1973 - Retires but continues her work as scientist into her eighties

In 1938, as Germany became an increasingly dangerous place for Jews, Ingeborg fled to the US where she went back to university, finally to qualify as a doctor.

Within a few years she met her husband, the biochemist Samuel Mitja Rapoport, who was himself a Jewish refugee from Vienna.

Infant mortality

But, by the 1950s, Ingeborg suddenly found herself once again on the wrong side of the authorities.

The McCarthy anti-communist trials meant that Ingeborg and her husband were at risk because of their left-wing views. So they fled again - back to Germany.

This time Ingeborg Rapoport went to communist East Berlin, where she worked as a paediatrician.

Eventually she became a paediatrics professor, holding Europe's first chair in neonatal medicine, at the renowned Charite hospital in East Berlin.

She was given a national prize for her work in dramatically reducing infant mortality in East Germany.

But for all her achievements, winning back at the age of 102 the doctorate stolen from her by the Nazis must rank among her most impressive.

- Published28 January 2015

- Published23 February 2015

- Published20 January 2015

- Published28 May 2015